Endocrinol Metab.

2017 Mar;32(1):47-57. 10.3803/EnM.2017.32.1.47.

The Implication of Coronary Artery Calcium Testing for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Diabetes

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA. rblankstein@partners.org

- 2Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

- 3Division of Cardiology, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Oakland, CA, USA.

- 4Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Oakland, CA, USA.

- 5Department of Medicine, Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA.

- 6Miami Cardiac & Vascular Institute, Baptist Health South Florida, Miami, FL, USA.

- KMID: 2413286

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2017.32.1.47

Abstract

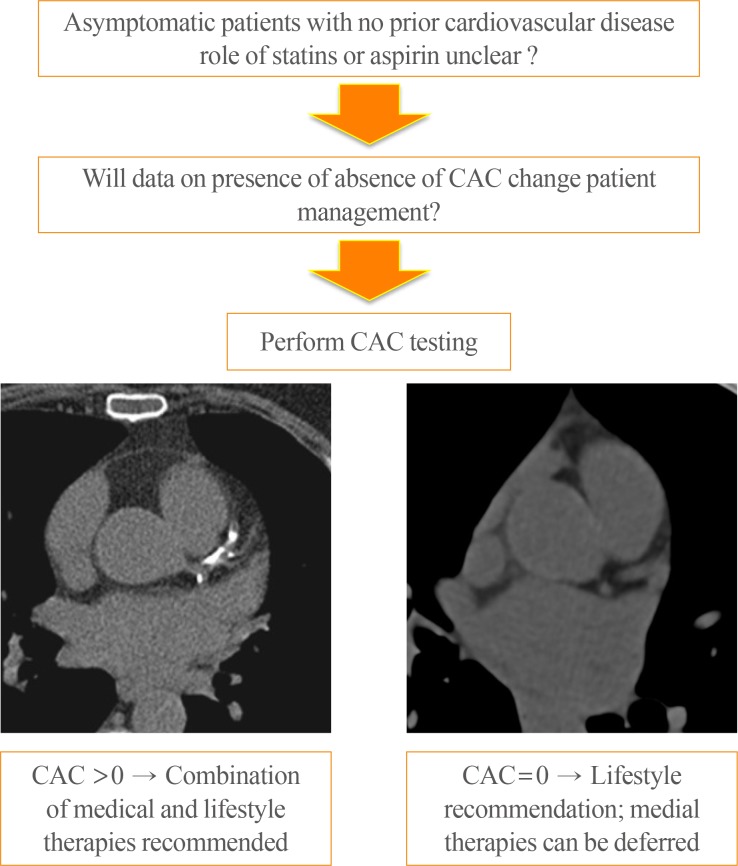

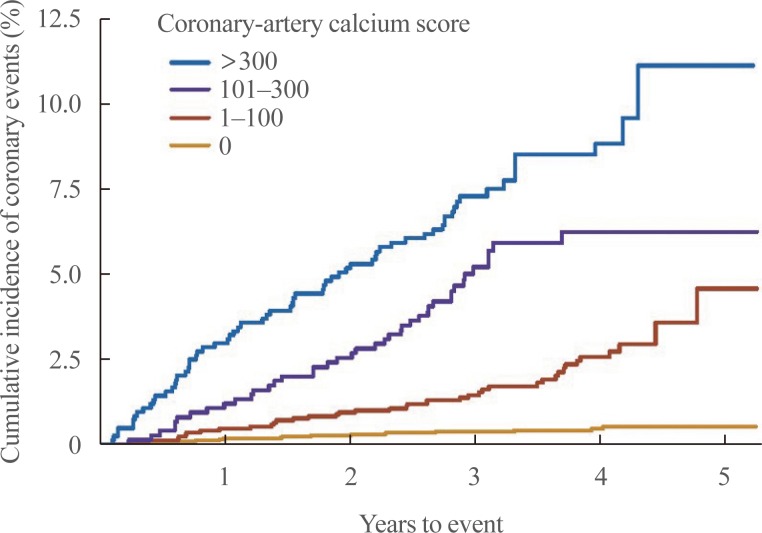

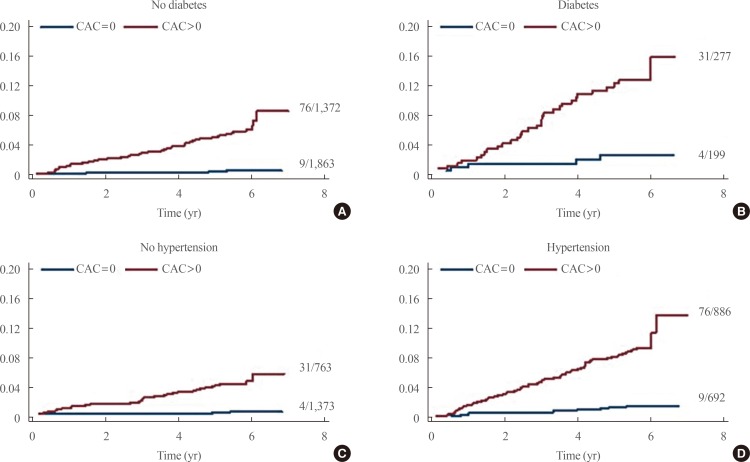

- Over the last two decades coronary artery calcium (CAC) scanning has emerged as a quick, safe, and inexpensive method to detect the presence of coronary atherosclerosis. Data from multiple studies has shown that compared to individuals who do not have any coronary calcifications, those with severe calcifications (i.e., CAC score >300) have a 10-fold increase in their risk of coronary heart disease events and cardiovascular disease. Conversely, those that have a CAC of 0 have a very low event rate (~0.1%/year), with data that now extends to 15 years in some studies. Thus, the most notable implication of identifying CAC in individuals who do not have known cardiovascular disease is that it allows targeting of more aggressive therapies to those who have the highest risk of having future events. Such identification of risk is especially important for individuals who are not on any therapies for coronary heart disease, or when intensification of treatment is being considered but has an uncertain role. This review will highlight some of the recent data on CAC testing, while focusing on the implications of those findings on patient management. The evolving role of CAC in patients with diabetes will also be highlighted.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Being Metabolically Healthy, the Most Responsible Factor for Vascular Health

Eun-Jung Rhee

Diabetes Metab J. 2018;42(1):19-25. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2018.42.1.19.The Influence of Obesity and Metabolic Health on Vascular Health

Eun-Jung Rhee

Endocrinol Metab. 2022;37(1):1-8. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2022.101.

Reference

-

1. Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, Bild DE, Burke G, Folsom AR, et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med. 2008; 358:1336–1345. PMID: 18367736.

Article2. Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, DeFilippis AP, Blankstein R, Rivera JJ, Agatston A, et al. Associations between C-reactive protein, coronary artery calcium, and cardiovascular events: implications for the JUPITER population from MESA, a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2011; 378:684–692. PMID: 21856482.

Article3. Blankstein R, Budoff MJ, Shaw LJ, Goff DC Jr, Polak JF, Lima J, et al. Predictors of coronary heart disease events among asymptomatic persons with low low-density lipoprotein cholesterol MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 58:364–374. PMID: 21757113.4. Silverman MG, Blaha MJ, Krumholz HM, Budoff MJ, Blankstein R, Sibley CT, et al. Impact of coronary artery calcium on coronary heart disease events in individuals at the extremes of traditional risk factor burden: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2014; 35:2232–2241. PMID: 24366919.

Article5. Polonsky TS, McClelland RL, Jorgensen NW, Bild DE, Burke GL, Guerci AD, et al. Coronary artery calcium score and risk classification for coronary heart disease prediction. JAMA. 2010; 303:1610–1616. PMID: 20424251.

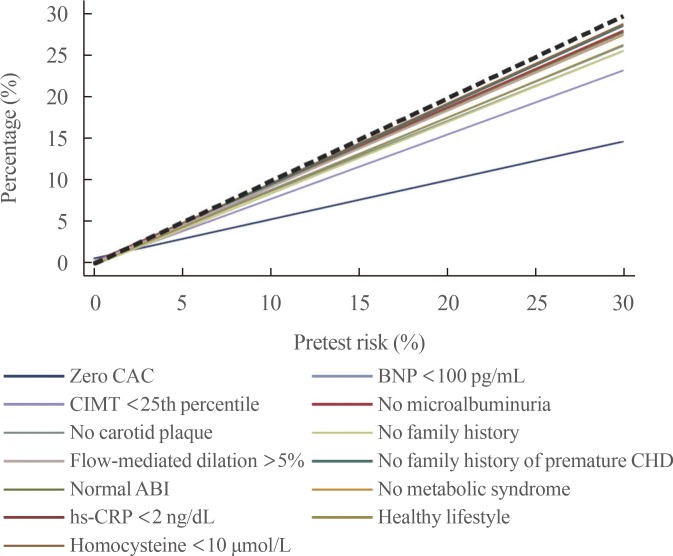

Article6. Yeboah J, McClelland RL, Polonsky TS, Burke GL, Sibley CT, O'Leary D, et al. Comparison of novel risk markers for improvement in cardiovascular risk assessment in intermediate-risk individuals. JAMA. 2012; 308:788–795. PMID: 22910756.

Article7. Kavousi M, Elias-Smale S, Rutten JH, Leening MJ, Vliegenthart R, Verwoert GC, et al. Evaluation of newer risk markers for coronary heart disease risk classification: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2012; 156:438–444. PMID: 22431676.8. Rana JS, Gransar H, Wong ND, Shaw L, Pencina M, Nasir K, et al. Comparative value of coronary artery calcium and multiple blood biomarkers for prognostication of cardiovascular events. Am J Cardiol. 2012; 109:1449–1453. PMID: 22425333.

Article9. Sarwar A, Shaw LJ, Shapiro MD, Blankstein R, Hoffmann U, Cury RC, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of absence of coronary artery calcification. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009; 2:675–688. PMID: 19520336.

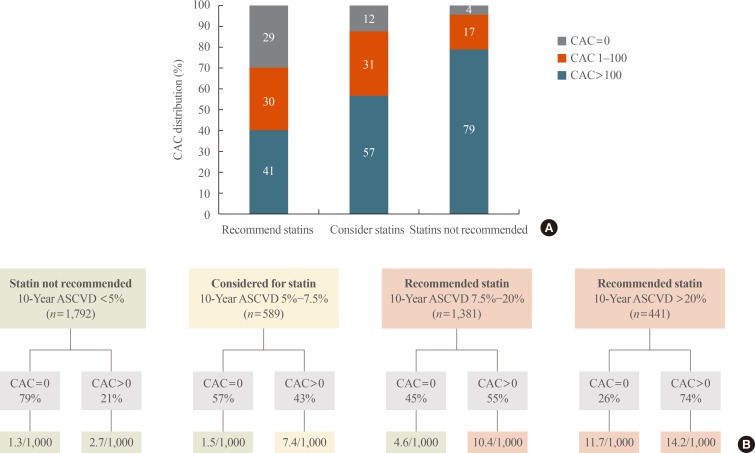

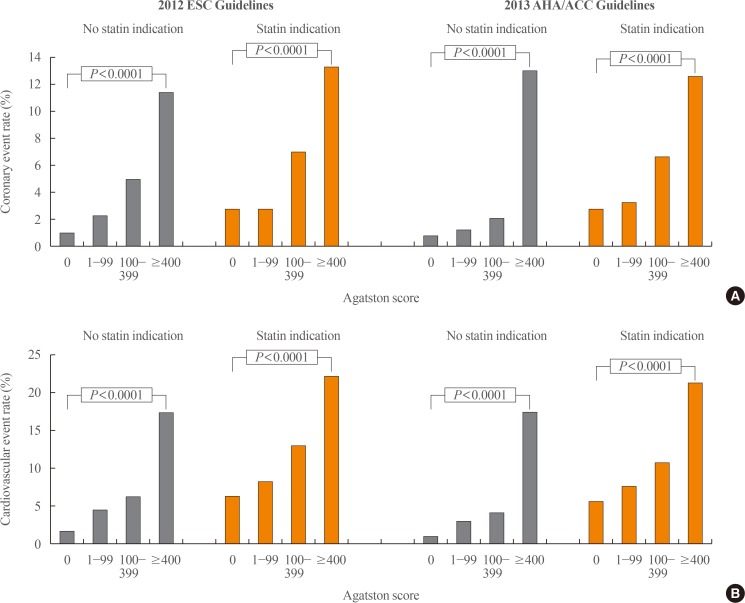

Article10. Blaha MJ, Cainzos-Achirica M, Greenland P, McEvoy JW, Blankstein R, Budoff MJ, et al. Role of coronary artery calcium score of zero and other negative risk markers for cardiovascular disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation. 2016; 133:849–858. PMID: 26801055.11. Tota-Maharaj R, Blaha MJ, McEvoy JW, Blumenthal RS, Muse ED, Budoff MJ, et al. Coronary artery calcium for the prediction of mortality in young adults <45 years old and elderly adults >75 years old. Eur Heart J. 2012; 33:2955–2962. PMID: 22843447.12. Blankstein R, Foody JM. Screening for coronary artery disease in patients with family history... how, when, and in whom? Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014; 7:417–419. PMID: 24847006.13. Nasir K, Bittencourt MS, Blaha MJ, Blankstein R, Agatson AS, Rivera JJ, et al. Implications of coronary artery calcium testing among statin candidates according to American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Cholesterol Management Guidelines: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015; 66:1657–1668. PMID: 26449135.14. Mahabadi AA, Mohlenkamp S, Lehmann N, Kalsch H, Dykun I, Pundt N, et al. CAC score improves coronary and CV risk assessment above statin indication by ESC and AHA/ACC primary prevention guidelines. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017; 10:143–153. PMID: 27665163.15. Messenger B, Li D, Nasir K, Carr JJ, Blankstein R, Budoff MJ. Coronary calcium scans and radiation exposure in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016; 32:525–529. PMID: 26515964.

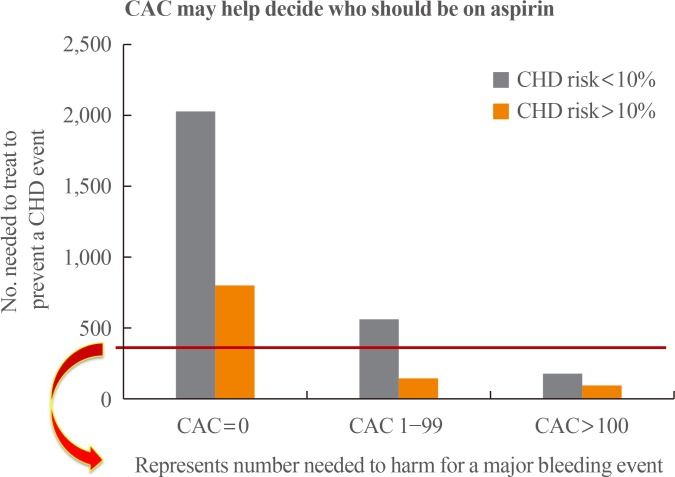

Article16. Miedema MD, Duprez DA, Misialek JR, Blaha MJ, Nasir K, Silverman MG, et al. Use of coronary artery calcium testing to guide aspirin utilization for primary prevention: estimates from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014; 7:453–460. PMID: 24803472.

Article17. McEvoy JW, Martin SS, Dardari ZA, Miedema MD, Sandfort V, Yeboah J, et al. Coronary artery calcium to guide a personalized risk-based approach to initiation and intensification of antihypertensive therapy. Circulation. 2017; 135:153–165. PMID: 27881560.

Article18. Reis JP, Loria CM, Lewis CE, Powell-Wiley TM, Wei GS, Carr JJ, et al. Association between duration of overall and abdominal obesity beginning in young adulthood and coronary artery calcification in middle age. JAMA. 2013; 310:280–288. PMID: 23860986.

Article19. Nasir K, Rubin J, Blaha MJ, Shaw LJ, Blankstein R, Rivera JJ, et al. Interplay of coronary artery calcification and traditional risk factors for the prediction of all-cause mortality in asymptomatic individuals. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012; 5:467–473. PMID: 22718782.

Article20. Carr JJ, Jacobs DR Jr, Terry JG, Shay CM, Sidney CM, Liu K, et al. Association of coronary artery calcium in adults aged 32 to 46 years with incident coronary heart disease and death. JAMA Cardiol. 2017; 2. 08. [Epub]. DOI: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.5493.

Article21. Blankstein R, Greenland P. Screening for coronary artery disease at an earlier age. JAMA Cardiol. 2017; 2. 08. [Epub]. DOI: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.5552.

Article22. Arad Y, Spadaro LA, Roth M, Newstein D, Guerci AD. Treatment of asymptomatic adults with elevated coronary calcium scores with atorvastatin, vitamin C, and vitamin E: the St. Francis Heart Study randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 46:166–172. PMID: 15992652.

Article23. Gupta A, Varshney R, Lau E, Hulten E, Bittencourt MS, Blaha MJ, et al. The identification of coronary atherosclerosis is associated with initiation of pharmacologic and lifestyle preventive therapies: a systematic review and metaanalysis. In : 2016 American College of Cardiology (ACC) 65th Annual Scientific Session and Expo; 2016 Apr 2-4; Chicago, IL.24. Rozanski A, Gransar H, Shaw LJ, Kim J, Miranda-Peats L, Wong ND, et al. Impact of coronary artery calcium scanning on coronary risk factors and downstream testing the EISNER (Early Identification of Subclinical Atherosclerosis by Noninvasive Imaging Research) prospective randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 57:1622–1632. PMID: 21439754.25. Orakzai RH, Nasir K, Orakzai SH, Kalia N, Gopal A, Musunuru K, et al. Effect of patient visualization of coronary calcium by electron beam computed tomography on changes in beneficial lifestyle behaviors. Am J Cardiol. 2008; 101:999–1002. PMID: 18359321.

Article26. Kalia NK, Miller LG, Nasir K, Blumenthal RS, Agrawal N, Budoff MJ. Visualizing coronary calcium is associated with improvements in adherence to statin therapy. Atherosclerosis. 2006; 185:394–399. PMID: 16051253.

Article27. Taylor AJ, Bindeman J, Feuerstein I, Le T, Bauer K, Byrd C, et al. Community-based provision of statin and aspirin after the detection of coronary artery calcium within a community-based screening cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 51:1337–1341. PMID: 18387433.

Article28. Nasir K, McClelland RL, Blumenthal RS, Goff DC Jr, Hoffmann U, Psaty BM, et al. Coronary artery calcium in relation to initiation and continuation of cardiovascular preventive medications: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010; 3:228–235. PMID: 20371760.29. Schwartz J, Allison M, Wright CM. Health behavior modification after electron beam computed tomography and physician consultation. J Behav Med. 2011; 34:148–155. PMID: 20857186.

Article30. O'Malley PG, Feuerstein IM, Taylor AJ. Impact of electron beam tomography, with or without case management, on motivation, behavioral change, and cardiovascular risk profile: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003; 289:2215–2223. PMID: 12734132.31. Obuchowski NA, Holden D, Modic MT, Cheah G, Fu AZ, Brant-Zawadzki M, et al. Total-body screening: preliminary results of a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Radiol. 2007; 4:604–611. PMID: 17845965.

Article32. Lederman J, Ballard J, Njike VY, Margolies L, Katz DL. Information given to postmenopausal women on coronary computed tomography may influence cardiac risk reduction efforts. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007; 60:389–396. PMID: 17346614.

Article33. Whelton SP, Nasir K, Blaha MJ, Gransar H, Metkus TS, Coresh J, et al. Coronary artery calcium and primary prevention risk assessment: what is the evidence? An updated meta-analysis on patient and physician behavior. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012; 5:601–607. PMID: 22811506.34. Mols RE, Jensen JM, Sand NP, Fuglesang C, Bagdat D, Vedsted P, et al. Visualization of coronary artery calcification: influence on risk modification. Am J Med. 2015; 128:1023.e23–1023.e31.

Article35. Gibson AO, Blaha MJ, Arnan MK, Sacco RL, Szklo M, Herrington DM, et al. Coronary artery calcium and incident cerebrovascular events in an asymptomatic cohort. The MESA study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014; 7:1108–1115. PMID: 25459592.36. Hermann DM, Gronewold J, Lehmann N, Moebus S, Jockel KH, Bauer M, et al. Coronary artery calcification is an independent stroke predictor in the general population. Stroke. 2013; 44:1008–1013. PMID: 23449263.

Article37. Bittencourt MS, Blankstein R, Mao S, Rivera JJ, Bertoni AG, Shaw LJ, et al. Left ventricular area on non-contrast cardiac computed tomography as a predictor of incident heart failure: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2016; 10:500–506. PMID: 27499493.38. Kalsch H, Lehmann N, Mohlenkamp S, Neumann T, Slomiany U, Schmermund A, et al. Association of coronary artery calcium and congestive heart failure in the general population: results of the Heinz Nixdorf recall study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2010; 99:175–182. PMID: 20054694.

Article39. O'Neal WT, Efird JT, Dawood FZ, Yeboah J, Alonso A, Heckbert SR, et al. Coronary artery calcium and risk of atrial fibrillation (from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). Am J Cardiol. 2014; 114:1707–1712. PMID: 25282316.40. Handy CE, Desai CS, Dardari ZA, Al-Mallah MH, Miedema MD, Ouyang P, et al. The association of coronary artery calcium with noncardiovascular disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016; 9:568–576. PMID: 26970999.41. Rana JS, Liu JY, Moffet HH, Jaffe M, Karter AJ. Diabetes and prior coronary heart disease are not necessarily risk equivalent for future coronary heart disease events. J Gen Intern Med. 2016; 31:387–393. PMID: 26666660.

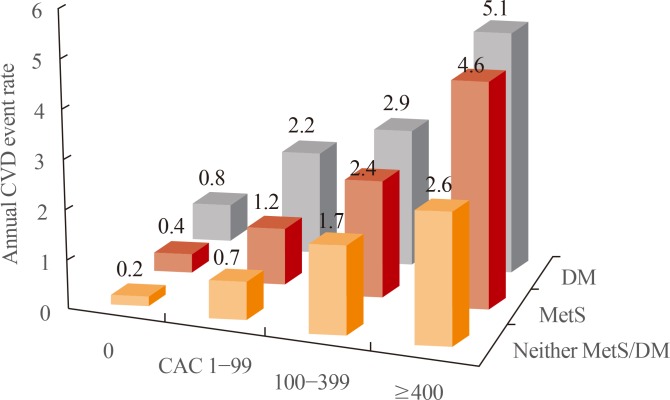

Article42. Rana JS, Blankstein R. Are all individuals with diabetes equal, or some more equal than others? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016; 9:1289–1291. PMID: 27568120.43. Young LH, Wackers FJ, Chyun DA, Davey JA, Barrett EJ, Taillefer R, et al. Cardiac outcomes after screening for asymptomatic coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: the DIAD study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009; 301:1547–1555. PMID: 19366774.44. Muhlestein JB, Lappe DL, Lima JA, Rosen BD, May HT, Knight S, et al. Effect of screening for coronary artery disease using CT angiography on mortality and cardiac events in high-risk patients with diabetes: the FACTOR-64 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014; 312:2234–2243. PMID: 25402757.45. Malik S, Budoff MJ, Katz R, Blumenthal RS, Bertoni AG, Nasir K, et al. Impact of subclinical atherosclerosis on cardiovascular disease events in individuals with metabolic syndrome and diabetes: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Diabetes Care. 2011; 34:2285–2290. PMID: 21844289.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Role of Coronary Artery Calcium Score Study: for the Prevention and Reduction of Obstructive Coronary Arterial Disease

- The Relation of Coronary Artery Calcium Scores with Framingham Risk Scores

- Diabetes and Heart Failure

- Preoperative Assessment of Cardiac Risk in the Patient with Diabetes

- Diabetes and Heart Failure