Clin Orthop Surg.

2017 Mar;9(1):116-125. 10.4055/cios.2017.9.1.116.

Outcome after Surgery for Metastases to the Pelvic Bone: A Single Institutional Experience

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea. hik19@snu.ac.kr

- 2Department of Surgical Oncology, Cancer Institute (WIA), Adyar, Chennai, India.

- KMID: 2412313

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4055/cios.2017.9.1.116

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

The pelvic bone is the most common site of bone metastases following the axial skeleton. Surgery on the pelvic bone is a demanding procedure. Few studies have been published on the surgical outcomes of metastasis to the pelvic bone with only small numbers of patients involved. This study sought to analyze the complications, local progression and survival after surgery for metastasis to the pelvic bone on a larger cohort of patients.

METHODS

We analyzed 83 patients who underwent surgery for metastases to the pelvic bone between the years 2000 and 2015. There were 41 men and 42 women with a mean age of 55 years. Possible factors that might be associated with complications, local progression and survival were investigated with regard to patient demographics and disease-related and treatment-related variables.

RESULTS

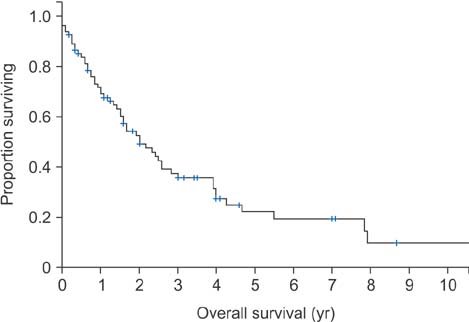

The overall complication rate was 16% (13/83). Advanced age (> 55 years, p = 0.034) and low preoperative serum albumin levels (≤ 39 g/L, p = 0.001) were associated with increased complication rates. In patients with periacetabular disease, the complication rate was higher in those who underwent total hip replacement arthroplasty (THR) than those who did not (p = 0.030). Local progression rate was 46% (37/83). The overall median time to local progression was 26 ± 14.3 months. The median time from local progression to death was 13 months (range, 0 to 81 months). The local progression-free survival was 52.6% ± 6.4% at 2 years and 36.4%± 7.6% at 5 years, respectively. Presence of skip lesions (p = 0.017) and presence of visceral metastasis (p = 0.027) were found to be significantly associated with local progression. The median survival of all patients was 24 months. The 2-year and 3-year survival rates were 52.5% ± 5.9% and 35.6% ± 6%, respectively. Metastasis from the kidney, breast, or thyroid or of hematolymphoid origin (p = 0.014), absence of visceral metastasis (p = 0.017) and higher preoperative serum albumin levels (p = 0.009) were associated with a prolonged survival.

CONCLUSIONS

Advanced age and low serum albumin levels were associated with high complication rates. Local progression after surgery for metastases to the pelvic bone was affected by the presence of skip lesions, not by surgical margins. Primary cancer type, serum albumin level and visceral metastasis influenced survival.

MeSH Terms

-

Abdominal Neoplasms/*secondary

Acetabulum

Adolescent

Adult

Age Factors

Aged

Arthroplasty, Replacement, Hip/adverse effects

Blood Loss, Surgical

Bone Neoplasms/*secondary/*surgery/therapy

Child

Disease Progression

Disease-Free Survival

*Embolization, Therapeutic

Female

Humans

Length of Stay

Male

Margins of Excision

Metastasectomy/*adverse effects

Middle Aged

*Pelvic Bones

Postoperative Complications/*etiology

Preoperative Period

Retrospective Studies

Serum Albumin/metabolism

Survival Rate

Treatment Outcome

Young Adult

Serum Albumin

Figure

Reference

-

1. Fukutomi M, Yokota M, Chuman H, et al. Increased incidence of bone metastases in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001; 13(9):1083–1088.

Article2. Li S, Peng Y, Weinhandl ED, et al. Estimated number of prevalent cases of metastatic bone disease in the US adult population. Clin Epidemiol. 2012; 4:87–93.3. Kakhki VR, Anvari K, Sadeghi R, Mahmoudian AS, Torabian-Kakhki M. Pattern and distribution of bone metastases in common malignant tumors. Nucl Med Rev Cent East Eur. 2013; 16(2):66–69.

Article4. Randall RL. Metastatic bone disease: an integrated approach to patient care. New York, NY: Springer;2016.5. Wood TJ, Racano A, Yeung H, Farrokhyar F, Ghert M, Deheshi BM. Surgical management of bone metastases: quality of evidence and systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014; 21(13):4081–4089.

Article6. Nilsson J, Gustafson P, Fornander P, Ornstein E. The Harrington reconstruction for advanced periacetabular metastatic destruction: good outcome in 32 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000; 71(6):591–596.

Article7. Quinn RH, Drenga J. Perioperative morbidity and mortality after reconstruction for metastatic tumors of the proximal femur and acetabulum. J Arthroplasty. 2006; 21(2):227–232.

Article8. Wunder JS, Ferguson PC, Griffin AM, Pressman A, Bell RS. Acetabular metastases: planning for reconstruction and review of results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003; 415 Suppl. S187–S197.

Article9. Marco RA, Sheth DS, Boland PJ, Wunder JS, Siegel JA, Healey JH. Functional and oncological outcome of acetabular reconstruction for the treatment of metastatic disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000; 82(5):642–651.

Article10. Kunisada T, Choong PF. Major reconstruction for periacetabular metastasis: early complications and outcome following surgical treatment in 40 hips. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000; 71(6):585–590.

Article11. Ji T, Guo W, Yang RL, Tang S, Sun X. Clinical outcome and quality of life after surgery for peri-acetabular metastases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011; 93(8):1104–1110.

Article12. Sorensen MS, Gerds TA, Hindso K, Petersen MM. Prediction of survival after surgery due to skeletal metastases in the extremities. Bone Joint J. 2016; 98(2):271–277.13. Bauer HC, Wedin R. Survival after surgery for spinal and extremity metastases: prognostication in 241 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1995; 66(2):143–146.

Article14. Dindo D, Clavien PA. What is a surgical complication? World J Surg. 2008; 32(6):939–941.

Article15. Bickels J, Dadia S, Lidar Z. Surgical management of metastatic bone disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009; 91(6):1503–1516.

Article16. Giurea A, Ritschl P, Windhager R, Kaider A, Helwig U, Kotz R. The benefits of surgery in the treatment of pelvic metastases. Int Orthop. 1997; 21(5):343–348.

Article17. Puri A, Pruthi M, Gulia A. Outcomes after limb sparing resection in primary malignant pelvic tumors. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014; 40(1):27–33.

Article18. Ruggieri P, Mavrogenis AF, Angelini A, Mercuri M. Metastases of the pelvis: does resection improve survival? Orthopedics. 2011; 34(7):e236–e244.

Article19. Goh SL, De Silva RP, Dhital K, Gett RM. Is low serum albumin associated with postoperative complications in patients undergoing oesophagectomy for oesophageal malignancies? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2015; 20(1):107–113.

Article20. Gohil R, Rishi M, Tan BH. Pre-operative serum albumin and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio are associated with prolonged hospital stay following colorectal cancer surgery. Br J Med Med Res. 2014; 4(1):481–487.

Article21. Han I, Lee YM, Cho HS, Oh JH, Lee SH, Kim HS. Outcome after surgical treatment of pelvic sarcomas. Clin Orthop Surg. 2010; 2(3):160–166.

Article22. Wirbel RJ, Schulte M, Mutschler WE. Surgical treatment of pelvic sarcomas: oncologic and functional outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001; (390):190–205.23. Pring ME, Weber KL, Unni KK, Sim FH. Chondrosarcoma of the pelvis: a review of sixty-four cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001; 83(11):1630–1642.24. Fottner A, Szalantzy M, Wirthmann L, et al. Bone metastases from renal cell carcinoma: patient survival after surgical treatment. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010; 11:145.

Article25. Langerhuizen DW, Janssen SJ, van der Vliet QM, et al. Metastasectomy, intralesional resection, or stabilization only in the treatment of bone metastases from renal cell carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2016; 114(2):237–245.

Article26. Enneking WF, Kagan A. The implications of “skip” metastases in osteosarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975; (111):33–41.

Article27. Kager L, Zoubek A, Kastner U, et al. Skip metastases in osteosarcoma: experience of the Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006; 24(10):1535–1541.

Article28. Yasko AW, Rutledge J, Lewis VO, Lin PP. Disease- and recurrence-free survival after surgical resection of solitary bone metastases of the pelvis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007; 459:128–132.

Article29. Gupta D, Lis CG. Pretreatment serum albumin as a predictor of cancer survival: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr J. 2010; 9:69.

Article30. Ratasvuori M, Wedin R, Hansen BH, et al. Prognostic role of en-bloc resection and late onset of bone metastasis in patients with bone-seeking carcinomas of the kidney, breast, lung, and prostate: SSG study on 672 operated skeletal metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2014; 110(4):360–365.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Clinical Experience of Undetected Pelvic Bone Fracture during Treatment of Pelvic Pain

- Surgical Treatment of Malunion and Nonunion after Pelvic Bone Fracture

- Management Trend for Unstable Pelvic Bone Fractures in Regional Trauma Centers: Multi-Institutional Study in the Republic of Korea

- Comparison of mortality between open and closed pelvic bone fractures in Korea using 1:2 propensity score matching: a single-center retrospective study

- Robotic or laparoscopic pelvic exenteration for gynecological malignancies: feasible options to open surgery