Clin Orthop Surg.

2017 Dec;9(4):521-528. 10.4055/cios.2017.9.4.521.

Analysis of Radiographic Parameters of the Forearm in Traumatic Radial Head Dislocation

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Biomedical Research Institute, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea. kimht@pusan.ac.kr

- 2Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam.

- KMID: 2412254

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4055/cios.2017.9.4.521

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Various deformities can occur in the forearm bones when the traumatically dislocated radial head is untreated for a long period. Without correction of all deformities, reduction of the dislocated radial head is difficult to maintain, and forearm and elbow motion will deteriorate after reduction. We evaluated radiographic parameters of forearms with traumatically dislocated radial heads (and of the normal sides) to understand the resulting deformities and the effectiveness of surgical treatment.

METHODS

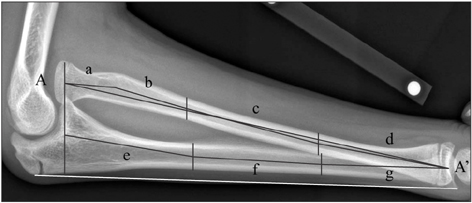

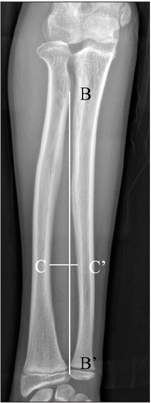

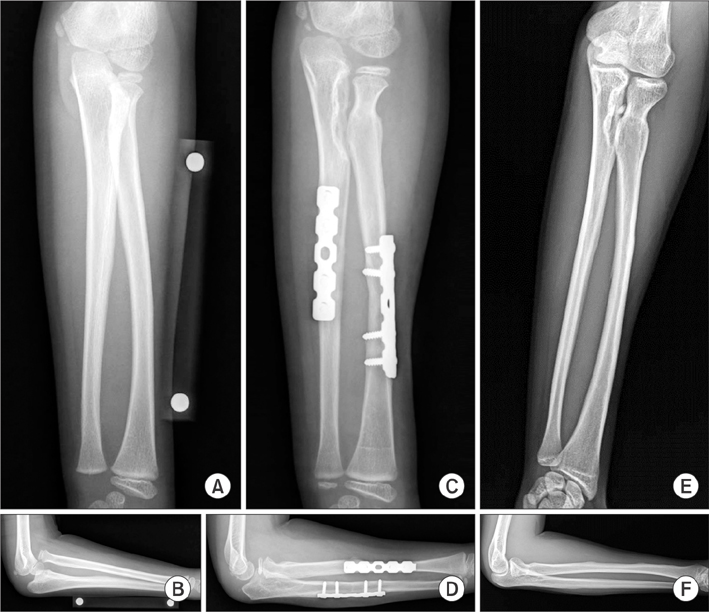

We analyzed pre- and postoperative anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of 22 forearms (22 patients) with traumatic radial head dislocation. We divided the forearm into three equal parts and measured various morphological parameters. All patients underwent surgical treatment and evaluation of radial head reduction and range of motion pre- and postoperatively.

RESULTS

Before treatment, the middle of the ulna was significantly different from the unaffected side in both anteroposterior and lateral views. After surgery, the proximal ulna was significantly different from the unaffected side and the abnormal proximal radial neck angle persisted. The radial head was successfully reduced in 20 of 22 cases. Overall, the mean range of motion decreased after surgery, except for increased flexion-extension.

CONCLUSIONS

Complicated deformities developing during long-term remodeling after injury indicate that stable reduction is difficult to achieve with conventional one-bone osteotomy. Even after successful reduction, secondary deformity in the proximal ulna and/or remaining deformity in the proximal radius can hinder forearm rotation.

MeSH Terms

-

Adolescent

Child

Child, Preschool

Elbow Joint/*diagnostic imaging/*injuries/physiopathology

Female

Forearm/physiopathology

Humans

Joint Deformities, Acquired/*diagnostic imaging/etiology/physiopathology/surgery

Joint Dislocations/complications/*diagnostic imaging/surgery

Male

Postoperative Period

Preoperative Period

Pronation

Radiography

Radius/*diagnostic imaging/surgery

Range of Motion, Articular

Retrospective Studies

Supination

Ulna/diagnostic imaging

Figure

Reference

-

1. Fowles JV, Sliman N, Kassab MT. The Monteggia lesion in children: fracture of the ulna and dislocation of the radial head. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983; 65(9):1276–1282.

Article2. Letts M, Locht R, Wiens J. Monteggia fracture-dislocations in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985; 67(5):724–727.

Article3. Kalamchi A. Monteggia fracture-dislocation in children: late treatment in two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986; 68(4):615–619.

Article4. Hirayama T, Takemitsu Y, Yagihara K, Mikita A. Operation for chronic dislocation of the radial head in children: reduction by osteotomy of the ulna. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987; 69(4):639–642.

Article5. Best TN. Management of old unreduced Monteggia fracture dislocations of the elbow in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1994; 14(2):193–199.

Article6. Tajima T, Yoshizu T. Treatment of long-standing dislocation of the radial head in neglected Monteggia fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 1995; 20(3 Pt 2):S91–S94.

Article7. Inoue G, Shionoya K. Corrective ulnar osteotomy for malunited anterior Monteggia lesions in children: 12 patients followed for 1-12 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998; 69(1):73–76.

Article8. Freedman L, Luk K, Leong JC. Radial head reduction after a missed Monteggia fracture: brief report. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988; 70(5):846–847.

Article9. Stoll TM, Willis RB, Paterson DC. Treatment of the missed Monteggia fracture in the child. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992; 74(3):436–440.

Article10. Bell Tawse AJ. The treatment of malunited anterior Monteggia fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1965; 47(4):718–723.

Article11. Lloyd-Roberts GC, Bucknill TM. Anterior dislocation of the radial head in children: aetiology, natural history and management. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1977; 59(4):402–407.

Article12. Hurst LC, Dubrow EN. Surgical treatment of symptomatic chronic radial head dislocation: a neglected Monteggia fracture. J Pediatr Orthop. 1983; 3(2):227–230.13. Oner FC, Diepstraten AF. Treatment of chronic post-traumatic dislocation of the radial head in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993; 75(4):577–581.

Article14. Seel MJ, Peterson HA. Management of chronic posttraumatic radial head dislocation in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1999; 19(3):306–312.

Article15. Rodgers WB, Waters PM, Hall JE. Chronic Monteggia lesions in children: complications and results of reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996; 78(9):1322–1329.

Article16. Horii E, Nakamura R, Koh S, Inagaki H, Yajima H, Nakao E. Surgical treatment for chronic radial head dislocation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002; 84(7):1183–1188.

Article17. Wang MN, Chang WN. Chronic posttraumatic anterior dislocation of the radial head in children: thirteen cases treated by open reduction, ulnar osteotomy, and annular ligament reconstruction through a Boyd incision. J Orthop Trauma. 2006; 20(1):1–5.

Article18. Kim HT, Conjares JN, Suh JT, Yoo CI. Chronic radial head dislocation in children. Part I: pathologic changes preventing stable reduction and surgical correction. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002; 22(5):583–590.

Article19. Futami T, Tsukamoto Y, Fujita T. Rotation osteotomy for dislocation of the radial head: 6 cases followed for 7 (3-10) years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1992; 63(4):455–456.20. Lincoln TL, Mubarak SJ. “Isolated” traumatic radial-head dislocation. J Pediatr Orthop. 1994; 14(4):454–457.

Article21. Oka K, Murase T, Moritomo H, Sugamoto K, Yoshikawa H. Morphologic evaluation of chronic radial head dislocation: three-dimensional and quantitative analyses. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010; 468(9):2410–2418.

Article22. Tatebe M, Shinohara T, Okui N, Yamamoto M, Kurimoto S, Hirata H. Tilt of the radius from forearm rotational axis reliably predicts rotational improvement after corrective osteotomy for malunited forearm fractures. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2012; 74(1-2):167–171.23. Wilkins KE. Changes in the management of monteggia fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002; 22(4):548–554.

Article24. Hui JH, Sulaiman AR, Lee HC, Lam KS, Lee EH. Open reduction and annular ligament reconstruction with fascia of the forearm in chronic monteggia lesions in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005; 25(4):501–506.

Article25. Morrey BF, Askew LJ, Chao EY. A biomechanical study of normal functional elbow motion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981; 63(6):872–877.

Article26. Colaris JW, Allema JH, Reijman M, et al. Which factors affect limitation of pronation/supination after forearm fractures in children? A prospective multicentre study. Injury. 2014; 45(4):696–700.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Traumatic Bowing of the Ulna with the Dislocation of the Radial Head: Report of a Case

- Acute Traumatic Irreducible Anterior Dislocation and Fracture of the Radial Head in an Adult

- One-Bone Forearm Procedure for Acquired Pseudoarthrosis of the Ulna Combined with Radial Head Dislocation in a Child: A Case with 20 Years Follow-Up

- Reconstruction of Neglected Traumatic Radial Head Dislocation in Children

- Isolated Traumatic Radial Head Anterior Dislocation Treated with Open Reduction in Children