J Nutr Health.

2017 Dec;50(6):565-577. 10.4163/jnh.2017.50.6.565.

Association between nutrient intake and serum high sensitivity C-reactive protein level in Korean adults: Using the data from 2015 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Food and Nutrition, Chungnam National University, Daejeon 34134, Korea. jacho@cnu.ac.kr

- 2Department of Food and Nutrition, Hannam University, Daejeon 34054, Korea.

- KMID: 2401013

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4163/jnh.2017.50.6.565

Abstract

- PURPOSE

There have been limited studies investigating the relationship between high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), metabolic diseases, and dietary factors in Korean adults. Here, we examined the association between nutrient intake and serum hsCRP among Korean adults.

METHODS

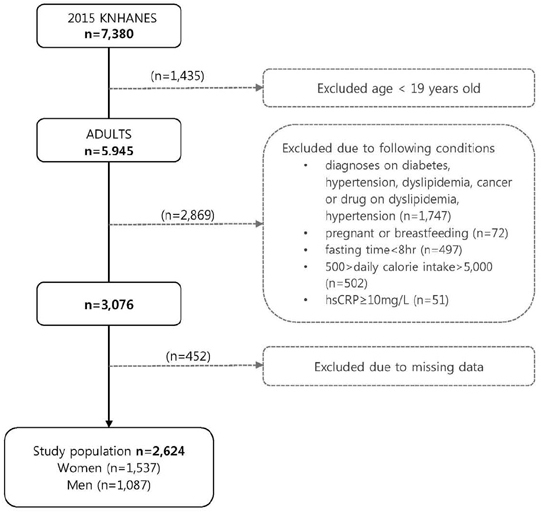

Using data on 2,624 healthy Korean adults (1,537 women and 1,087 men) from the 2015 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, demographic, anthropometric, biochemical, and dietary factors were analyzed once the subjects were grouped into either sex, age, or BMI. Nutrient intake was evaluated using the dietary data obtained by one-day 24-hour recall. Based on the guidelines of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association, hsCRP level was classified as HCRPG (High CRP Group, hsCRP > 1 mg/L) and LCRPG (Low CRP Group, hsCRP ≤ 1 mg/L). Proc surveyreg procedure was performed to examine the associations between nutrient intake and hsCRP after adjustment for potential confounding variables.

RESULTS

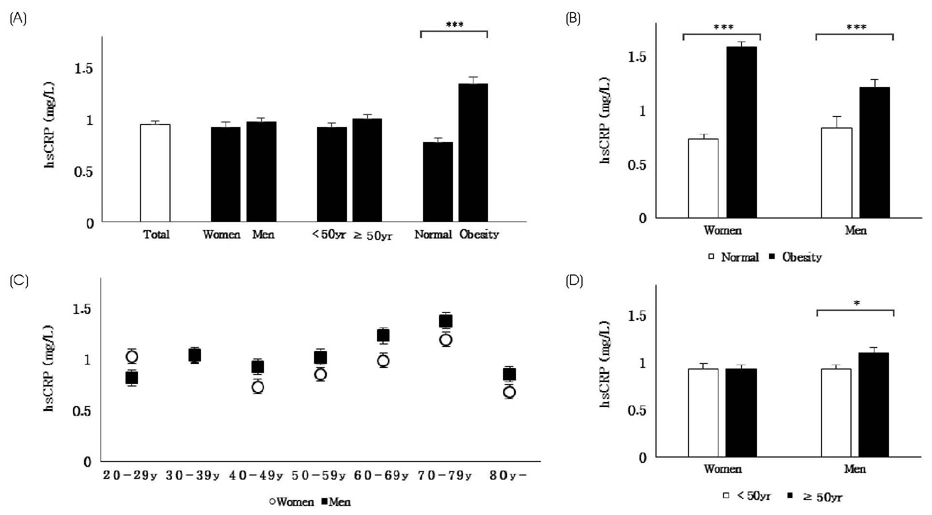

The average hsCRP level of healthy Korean adults was 0.95 ±0.03 mg/L (0.97 ±0.04 mg/L in men, 0.92 ±0.05 mg/L in women). Obese subjects had significantly higher hsCRP than non-obese subjects in both sexes. The hsCRP level was positively associated with current smoking, physical inactivity, BMI, waist circumference, fasting blood glucose, triglycerides, total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, and blood pressure and inversely associated with HDL-cholesterol. LCRPG had significantly higher intake of dietary fiber compared to HCRPG in women. High hsCRP level was associated with more dietary cholesterol intake but less omega-3 fatty acid intake among subjects aged ≥ 50y. HCRPG of obese subjects had higher intakes of fat and saturated fatty acid than LCRPG.

CONCLUSION

The hsCRP level is closely associated with several lifestyle variables and nutrient intake in healthy Korean adults. Individuals with high hsCRP level show low intakes of dietary fiber and omega-3 fatty acids but high intakes of dietary fat and cholesterol. Our findings suggest that a potential anti-inflammatory role for nutrients and lifestyle in the Korean adult population.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Adult*

American Heart Association

Blood Glucose

Blood Pressure

C-Reactive Protein*

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.)

Cholesterol

Cholesterol, Dietary

Confounding Factors (Epidemiology)

Dietary Fats

Dietary Fiber

Fasting

Fatty Acids, Omega-3

Female

Humans

Korea*

Life Style

Male

Metabolic Diseases

Nutrition Surveys*

Smoke

Smoking

Triglycerides

Waist Circumference

Blood Glucose

C-Reactive Protein

Cholesterol

Cholesterol, Dietary

Dietary Fats

Fatty Acids, Omega-3

Smoke

Triglycerides

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Effects of Korean diet control nutrition education on cardiovascular disease risk factors in patients who underwent cardiovascular disease surgery

Su-Jin Jung, Soo-Wan Chae

J Nutr Health. 2018;51(3):215-227. doi: 10.4163/jnh.2018.51.3.215.

Reference

-

1. GBD 2013 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015; 386(10010):2287–2323.2. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic disease status and issues. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2015.3. Majno G, Joris I. Cells, tissues, and disease: principles of general pathology. 2nd edition. New York (NY): Oxford University Press;2004.4. Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008; 454(7203):428–435.

Article5. Hussain SP, Hofseth LJ, Harris CC. Radical causes of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003; 3(4):276–285.

Article6. Vigushin DM, Pepys MB, Hawkins PN. Metabolic and scintigraphic studies of radioiodinated human C-reactive protein in health and disease. J Clin Invest. 1993; 91(4):1351–1357.

Article7. Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, Anderson JL, Cannon RO 3rd, Criqui M, Fadl YY, Fortmann SP, Hong Y, Myers GL, Rifai N, Smith SC Jr, Taubert K, Tracy RP, Vinicor F. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. American Heart Association. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003; 107(3):499–511.8. Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Tracy RP, Corti MC, Wacholder S, Ettinger WH Jr, Heimovitz H, Cohen HJ, Wallace R. Associations of elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly. Am J Med. 1999; 106(5):506–512.9. Kones R. Rosuvastatin, inflammation, C-reactive protein, JUPITER, and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease--a perspective. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2010; 4:383–413.10. McLaughlin T, Abbasi F, Lamendola C, Liang L, Reaven G, Schaaf P, Reaven P. Differentiation between obesity and insulin resistance in the association with C-reactive protein. Circulation. 2002; 106(23):2908–2912.

Article11. Tracy RP, Psaty BM, Macy E, Bovill EG, Cushman M, Cornell ES, Kuller LH. Lifetime smoking exposure affects the association of C-reactive protein with cardiovascular disease risk factors and subclinical disease in healthy elderly subjects. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997; 17(10):2167–2176.

Article12. Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Sharrett AR, Lindberg G, Savage PJ, Offenbacher S, Azambuja MI, Tracy RP, Heiss G. Markers of inflammation and prediction of diabetes mellitus in adults (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study): a cohort study. Lancet. 1999; 353(9165):1649–1652.

Article13. Muhammad IF, Borné Y, Hedblad B, Nilsson PM, Persson M, Engström G. Acute-phase proteins and incidence of diabetes: a population-based cohort study. Acta Diabetol. 2016; 53(6):981–989.

Article14. Albert MA, Glynn RJ, Buring J, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein levels among women of various ethnic groups living in the United States (from the Women's Health Study). Am J Cardiol. 2004; 93(10):1238–1242.

Article15. Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, Tracy RP, Hennekens CH. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med. 1997; 336(14):973–979.16. Esmaillzadeh A, Kimiagar M, Mehrabi Y, Azadbakht L, Hu FB, Willett WC. Fruit and vegetable intakes, C-reactive protein, and the metabolic syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006; 84(6):1489–1497.

Article17. Albert MA, Glynn RJ, Ridker PM. Alcohol consumption and plasma concentration of C-reactive protein. Circulation. 2003; 107(3):443–447.

Article18. Soltani S, Chitsazi MJ, Salehi-Abargouei A. The effect of dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) on serum inflammatory markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Clin Nutr. 2017; Forthcoming.

Article19. Khayyatzadeh SS, Kazemi-Bajestani SM, Bagherniya M, Mehramiz M, Tayefi M, Ebrahimi M, Ferns GA, Safarian M, Ghayour-Mobarhan M. Serum high C reactive protein concentrations are related to the intake of dietary macronutrients and fiber: findings from a large representative Persian population sample. Clin Biochem. 2017; 50(13-14):750–755.

Article20. Ajani UA, Ford ES, Mokdad AH. Dietary fiber and C-reactive protein: findings from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. J Nutr. 2004; 134(5):1181–1185.

Article21. King DE, Egan BM, Geesey ME. Relation of dietary fat and fiber to elevation of C-reactive protein. Am J Cardiol. 2003; 92(11):1335–1339.

Article22. Lee Y, Kang D, Lee SA. Effect of dietary patterns on serum C-reactive protein level. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014; 24(9):1004–1011.

Article23. WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004; 363(9403):157–163.24. Ma Y, Griffith JA, Chasan-Taber L, Olendzki BC, Jackson E, Stanek EJ 3rd, Li W, Pagoto SL, Hafner AR, Ockene IS. Association between dietary fiber and serum C-reactive protein. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006; 83(4):760–766.

Article25. Ma Y, Hébert JR, Li W, Bertone-Johnson ER, Olendzki B, Pagoto SL, Tinker L, Rosal MC, Ockene IS, Ockene JK, Griffith JA, Liu S. Association between dietary fiber and markers of systemic inflammation in the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study. Nutrition. 2008; 24(10):941–949.

Article26. Bode JG, Albrecht U, Häussinger D, Heinrich PC, Schaper F. Hepatic acute phase proteins--regulation by IL-6- and IL-1-type cytokines involving STAT3 and its crosstalk with NF-κ B-dependent signaling. Eur J Cell Biol. 2012; 91(6-7):496–505.27. Wilkins J, Gallimore JR, Moore EG, Pepys MB. Rapid automated high sensitivity enzyme immunoassay of C-reactive protein. Clin Chem. 1998; 44(6 Pt 1):1358–1361.

Article28. Ledue TB, Rifai N. High sensitivity immunoassays for C-reactive protein: promises and pitfalls. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2001; 39(11):1171–1176.

Article29. Folsom AR, Aleksic N, Catellier D, Juneja HS, Wu KK. C-reactive protein and incident coronary heart disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study. Am Heart J. 2002; 144(2):233–238.

Article30. Yang EY, Nambi V, Tang Z, Virani SS, Boerwinkle E, Hoogeveen RC, Astor BC, Mosley TH, Coresh J, Chambless L, Ballantyne CM. Clinical implications of JUPITER (Justification for the Use of statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin) in a U.S. population insights from the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 54(25):2388–2395.31. Hur M, Lee YK, Kang HJ, Lee KM. Distribution of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in Korean healthy individuals. J Clin Pathol Qual Control. 2001; 23(2):259–263.32. Lear SA, Chen MM, Birmingham CL, Frohlich JJ. The relationship between simple anthropometric indices and C-reactive protein: ethnic and gender differences. Metabolism. 2003; 52(12):1542–1546.

Article33. Anand SS, Razak F, Yi Q, Davis B, Jacobs R, Vuksan V, Lonn E, Teo K, McQueen M, Yusuf S. C-reactive protein as a screening test for cardiovascular risk in a multiethnic population. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004; 24(8):1509–1515.

Article34. Rallidis LS, Kolomvotsou A, Lekakis J, Farajian P, Vamvakou G, Dagres N, Zolindaki M, Efstathiou S, Anastasiou-Nana M, Zampelas A. Short-term effects of Mediterranean-type diet intervention on soluble cellular adhesion molecules in subjects with abdominal obesity. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2017; 17:38–43.

Article35. Brown L, Rosner B, Willett WW, Sacks FM. Cholesterol-lowering effects of dietary fiber: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999; 69(1):30–42.

Article36. Vinolo MA, Rodrigues HG, Nachbar RT, Curi R. Regulation of inflammation by short chain fatty acids. Nutrients. 2011; 3(10):858–876.

Article37. Blake GJ, Ridker PM. Inflammatory bio-markers and cardiovascular risk prediction. J Intern Med. 2002; 252(4):283–294.

Article38. Lemieux I, Pascot A, Prud’homme D, Alméras N, Bogaty P, Nadeau A, Bergeron J, Després JP. Elevated C-reactive protein: another component of the atherothrombotic profile of abdominal obesity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001; 21(6):961–967.39. Navarro SL, Kantor ED, Song X, Milne GL, Lampe JW, Kratz M, White E. Factors associated with multiple biomarkers of systemic inflammation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016; 25(3):521–531.

Article40. Jafari Salim S, Alizadeh S, Djalali M, Nematipour E, Hassan Javanbakht M. Effect of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation on body composition and circulating levels of follistatin-like 1 in males with coronary artery disease: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Am J Mens Health. 2017; 11(6):1758–1764.

Article41. Calder PC. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation, and immunity. Lipids. 2001; 36(9):1007–1024.

Article42. Fröhlich M, Sund M, Löwel H, Imhof A, Hoffmeister A, Koenig W. Independent association of various smoking characteristics with markers of systemic inflammation in men. Results from a representative sample of the general population (MONICA Augsburg Survey 1994/95). Eur Heart J. 2003; 24(14):1365–1372.43. Donges CE, Duffield R, Drinkwater EJ. Effects of resistance or aerobic exercise training on interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and body composition. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010; 42(2):304–313.

Article44. Richardson MR, Churilla JR. Sleep duration and C-reactive protein in US adults. South Med J. 2017; 110(4):314–317.

Article45. Ironson G, Banerjee N, Fitch C, Krause N. Positive emotional well-being, health behaviors, and inflammation measured by C-reactive protein. Soc Sci Med. 2017; Forthcoming.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Food and Nutrient Consumption Patterns of Korean Adults Based on their Levels of Self Reported Stress

- Nutrient Intake Patterns of Koreans by the Economic Status Using 1998 Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey

- Association between Dietary Protein Intake and Serum High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein Level in the Korean Elderly with Diabetes: Based on the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2016–2018

- Association between Carbonated Beverage Intake and High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein in Korean Adults

- Regional differences in protein intake and protein sources of Korean older adults and their association with metabolic syndrome using the 2016–2019 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys: a cross-sectional study