Endocrinol Metab.

2017 Sep;32(3):339-349. 10.3803/EnM.2017.32.3.339.

Calcium and Cardiovascular Disease

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Medicine, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand. i.reid@auckland.ac.nz

- 2Department of Endocrinology, Auckland District Health Board, Auckland, New Zealand.

- KMID: 2389814

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2017.32.3.339

Abstract

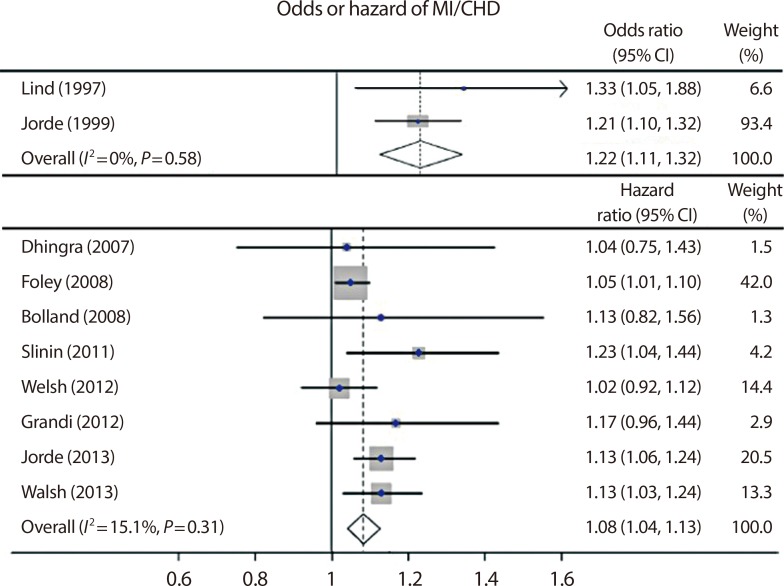

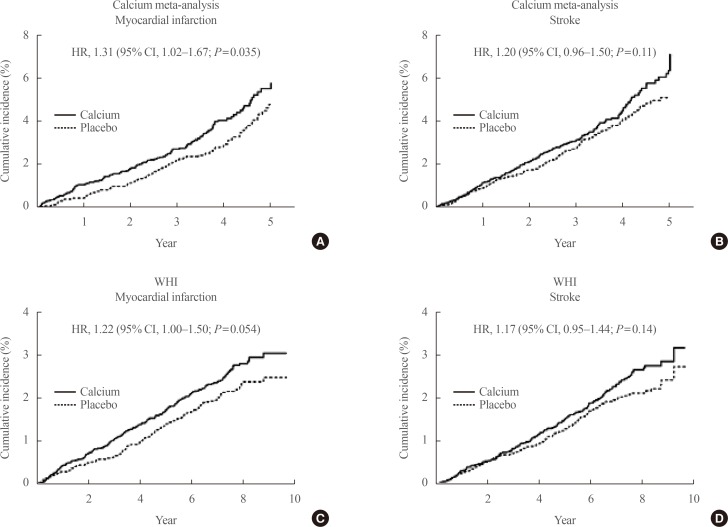

- Circulating calcium is a risk factor for vascular disease, a conclusion arising from prospective studies involving hundreds of thousands of participants and extending over periods of up to 30 years. These associations may be partially mediated by other cardiovascular risk factors such as circulating lipid levels, blood pressure, and body mass index, but there appears to be a residual independent effect of serum calcium. Polymorphisms of the calcium-sensing receptor associated with small elevations of serum calcium are also associated with cardiovascular disease, suggesting that calcium plays a causative role. Trials of calcium supplements in patients on dialysis and those with less severe renal failure demonstrate increased mortality and/or acceleration of vascular disease, and meta-analyses of trials in those without overt renal disease suggest a similar adverse effect. Interpretation of the latter trials is complicated by a significant interaction between baseline use of calcium supplements and the effect of randomisation to calcium in the largest trial. Restriction of analysis to those who are calcium-naive demonstrates a consistent adverse effect. Observational studies of dietary calcium do not demonstrate a consistent adverse effect on cardiovascular health, though very high or very low intakes may be deleterious. Thus, obtaining calcium from the diet rather than supplements is to be encouraged.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Effects of Altered Calcium Metabolism on Cardiac Parameters in Primary Aldosteronism

Jung Soo Lim, Namki Hong, Sungha Park, Sung Il Park, Young Taik Oh, Min Heui Yu, Pil Yong Lim, Yumie Rhee

Endocrinol Metab. 2018;33(4):485-492. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2018.33.4.485.

Reference

-

1. Reid IR, Gamble GD, Bolland MJ. Circulating calcium concentrations, vascular disease and mortality: a systematic review. J Intern Med. 2016; 279:524–540. PMID: 26749423.

Article2. Jorde R, Sundsfjord J, Fitzgerald P, Bonaa KH. Serum calcium and cardiovascular risk factors and diseases: the Tromso study. Hypertension. 1999; 34:484–490. PMID: 10489398.3. Foley RN, Collins AJ, Ishani A, Kalra PA. Calcium-phosphate levels and cardiovascular disease in community-dwelling adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am Heart J. 2008; 156:556–563. PMID: 18760141.

Article4. Yu N, Donnan PT, Flynn RW, Murphy MJ, Smith D, Rudman A, et al. Increased mortality and morbidity in mild primary hyperparathyroid patients. The Parathyroid Epidemiology and Audit Research Study (PEARS). Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010; 73:30–34. PMID: 20039887.5. Procopio M, Barale M, Bertaina S, Sigrist S, Mazzetti R, Loiacono M, et al. Cardiovascular risk and metabolic syndrome in primary hyperparathyroidism and their correlation to different clinical forms. Endocrine. 2014; 47:581–589. PMID: 24287796.

Article6. Shin S, Kim KJ, Chang HJ, Cho I, Kim YJ, Choi BW, et al. Impact of serum calcium and phosphate on coronary atherosclerosis detected by cardiac computed tomography. Eur Heart J. 2012; 33:2873–2881. PMID: 22719023.

Article7. Kwak SM, Kim JS, Choi Y, Chang Y, Kwon MJ, Jung JG, et al. Dietary intake of calcium and phosphorus and serum concentration in relation to the risk of coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic adults. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014; 34:1763–1769. PMID: 24925973.

Article8. Bolland MJ, Wang TK, van Pelt NC, Horne AM, Mason BH, Ames RW, et al. Abdominal aortic calcification on vertebral morphometry images predicts incident myocardial infarction. J Bone Miner Res. 2010; 25:505–512. PMID: 19821777.

Article9. Ishizaka N, Ishizaka Y, Takahashi E, Tooda E, Hashimoto H, Nagai R, et al. Serum calcium concentration and carotid artery plaque: a population-based study. J Cardiol. 2002; 39:151–157. PMID: 11912949.10. Rubin MR, Rundek T, McMahon DJ, Lee HS, Sacco RL, Silverberg SJ. Carotid artery plaque thickness is associated with increased serum calcium levels: the Northern Manhattan study. Atherosclerosis. 2007; 194:426–432. PMID: 17030035.

Article11. Piovesan A, Molineri N, Casasso F, Emmolo I, Ugliengo G, Cesario F. Left ventricular hypertrophy in primary hyperparathyroidism. Effects of successful parathyroidectomy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1999; 50:321–328. PMID: 10435057.

Article12. Nilsson IL, Aberg J, Rastad J, Lind L. Endothelial vasodilatory dysfunction in primary hyperparathyroidism is reversed after parathyroidectomy. Surgery. 1999; 126:1049–1055. PMID: 10598187.

Article13. Palmer M, Adami HO, Krusemo UB, Ljunghall S. Increased risk of malignant diseases after surgery for primary hyperparathyroidism. A nationwide cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 1988; 127:1031–1040. PMID: 3358404.14. Luigi P, Chiara FM, Laura Z, Cristiano M, Giuseppina C, Luciano C, et al. Arterial hypertension, metabolic syndrome and subclinical cardiovascular organ damage in patients with asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism before and after parathyroidectomy: preliminary results. Int J Endocrinol. 2012; 2012:408295. PMID: 22719761.

Article15. Hagstrom E, Lundgren E, Lithell H, Berglund L, Ljunghall S, Hellman P, et al. Normalized dyslipidaemia after parathyroidectomy in mild primary hyperparathyroidism: population-based study over five years. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2002; 56:253–260. PMID: 11874418.16. Khaleeli AA, Johnson JN, Taylor WH. Prevalence of glucose intolerance in primary hyperparathyroidism and the benefit of parathyroidectomy. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2007; 23:43–48. PMID: 16703622.

Article17. Vestergaard P, Mollerup CL, Frokjaer VG, Christiansen P, Blichert-Toft M, Mosekilde L. Cardiovascular events before and after surgery for primary hyperparathyroidism. World J Surg. 2003; 27:216–222. PMID: 12616440.

Article18. Neunteufl T, Heher S, Prager G, Katzenschlager R, Abela C, Niederle B, et al. Effects of successful parathyroidectomy on altered arterial reactivity in patients with hypercalcaemia: results of a 3-year follow-up study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2000; 53:229–233. PMID: 10931105.

Article19. Bernini G, Moretti A, Lonzi S, Bendinelli C, Miccoli P, Salvetti A. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in primary hyperparathyroidism before and after surgery. Metabolism. 1999; 48:298–300. PMID: 10094103.

Article20. Bollerslev J, Rosen T, Mollerup CL, Nordenstrom J, Baranowski M, Franco C, et al. Effect of surgery on cardiovascular risk factors in mild primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009; 94:2255–2261. PMID: 19351725.

Article21. Marz W, Seelhorst U, Wellnitz B, Tiran B, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Renner W, et al. Alanine to serine polymorphism at position 986 of the calcium-sensing receptor associated with coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, all-cause, and cardiovascular mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007; 92:2363–2369. PMID: 17374704.22. Lamas GA, Goertz C, Boineau R, Mark DB, Rozema T, Nahin RL, et al. Effect of disodium EDTA chelation regimen on cardiovascular events in patients with previous myocardial infarction: the TACT randomized trial. JAMA. 2013; 309:1241–1250. PMID: 23532240.23. Kamycheva E, Jorde R, Haug E, Sager G, Sundsfjord J. Effects of acute hypercalcaemia on blood pressure in subjects with and without parathyroid hormone secretion. Acta Physiol Scand. 2005; 184:113–119. PMID: 15916671.

Article24. Nilsson IL, Rastad J, Johansson K, Lind L. Endothelial vasodilatory function and blood pressure response to local and systemic hypercalcemia. Surgery. 2001; 130:986–990. PMID: 11742327.

Article25. Bristow SM, Gamble GD, Stewart A, Horne AM, Reid IR. Acute effects of calcium supplements on blood pressure and blood coagulation: secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial in post-menopausal women. Br J Nutr. 2015; 114:1868–1874. PMID: 26420590.

Article26. Billington EO, Bristow SM, Gamble GD, de Kwant JA, Stewart A, Mihov BV, et al. Acute effects of calcium supplements on blood pressure: randomised, crossover trial in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2017; 28:119–125. PMID: 27543500.

Article27. Daly R, Ebeling P, Khan B, Nowson C. Effects of calcium-vitamin D3 fortified milk on abdominal aortic calcification in older men: retrospective analysis of a 2-year randomised controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2009; 24(Suppl 1):S65–S66.28. Li S, Na L, Li Y, Gong L, Yuan F, Niu Y, et al. Long-term calcium supplementation may have adverse effects on serum cholesterol and carotid intima-media thickness in postmenopausal women: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013; 98:1353–1359. PMID: 24047919.

Article29. Anderson JJ, Kruszka B, Delaney JA, He K, Burke GL, Alonso A, et al. Calcium intake from diet and supplements and the risk of coronary artery calcification and its progression among older adults: 10-year follow-up of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). J Am Heart Assoc. 2016; 5:e003815. PMID: 27729333.

Article30. House MG, Kohlmeier L, Chattopadhyay N, Kifor O, Yamaguchi T, Leboff MS, et al. Expression of an extracellular calcium-sensing receptor in human and mouse bone marrow cells. J Bone Miner Res. 1997; 12:1959–1970. PMID: 9421228.

Article31. Hilgard P. Experimental hypercalcaemia and whole blood clotting. J Clin Pathol. 1973; 26:616–619. PMID: 4200324.

Article32. James MF, Roche AM. Dose-response relationship between plasma ionized calcium concentration and thrombelastography. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2004; 18:581–586. PMID: 15578468.

Article33. Yilmaz H. Assessment of mean platelet volume (MPV) in primary hyperparathyroidism: effects of successful parathyroidectomy on MPV levels. Endocr Regul. 2014; 48:182–188. PMID: 25512191.

Article34. Bristow SM, Gamble GD, Stewart A, Kalluru R, Horne AM, Reid IR. Acute effects of calcium citrate with or without a meal, calcium-fortified juice and a dairy product meal on serum calcium and phosphate: a randomised cross-over trial. Br J Nutr. 2015; 113:1585–1594. PMID: 25851635.

Article35. Kruger MC, von Hurst PR, Booth CL, Kuhn-Sherlock B, Todd JM, Schollum LM. Postprandial metabolic responses of serum calcium, parathyroid hormone and C-telopeptide of type I collagen to three doses of calcium delivered in milk. J Nutr Sci. 2014; 3:e6. PMID: 25191614.

Article36. Bristow SM, Gamble GD, Stewart A, Horne L, House ME, Aati O, et al. Acute and 3-month effects of microcrystalline hydroxyapatite, calcium citrate and calcium carbonate on serum calcium and markers of bone turnover: a randomised controlled trial in postmenopausal women. Br J Nutr. 2014; 112:1611–1620. PMID: 25274192.

Article37. Jamal SA, Vandermeer B, Raggi P, Mendelssohn DC, Chatterley T, Dorgan M, et al. Effect of calcium-based versus non-calcium-based phosphate binders on mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013; 382:1268–1277. PMID: 23870817.

Article38. Russo D, Miranda I, Ruocco C, Battaglia Y, Buonanno E, Manzi S, et al. The progression of coronary artery calcification in predialysis patients on calcium carbonate or sevelamer. Kidney Int. 2007; 72:1255–1261. PMID: 17805238.

Article39. Di Iorio B, Bellasi A, Russo D. INDEPENDENT Study Investigators. Mortality in kidney disease patients treated with phosphate binders: a randomized study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012; 7:487–493. PMID: 22241819.

Article40. Bolland MJ, Barber PA, Doughty RN, Mason B, Horne A, Ames R, et al. Vascular events in healthy older women receiving calcium supplementation: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008; 336:262–266. PMID: 18198394.

Article41. Bolland MJ, Avenell A, Baron JA, Grey A, MacLennan GS, Gamble GD, et al. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010; 341:c3691. PMID: 20671013.

Article42. Hsia J, Heiss G, Ren H, Allison M, Dolan NC, Greenland P, et al. Calcium/vitamin D supplementation and cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2007; 115:846–854. PMID: 17309935.

Article43. Bolland MJ, Grey A, Avenell A, Gamble GD, Reid IR. Calcium supplements with or without vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular events: reanalysis of the Women's Health Initiative limited access dataset and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011; 342:d2040. PMID: 21505219.

Article44. Radford LT, Bolland MJ, Gamble GD, Grey A, Reid IR. Subgroup analysis for the risk of cardiovascular disease with calcium supplements. Bonekey Rep. 2013; 2:293. PMID: 23951541.

Article45. Lewis JR, Radavelli-Bagatini S, Rejnmark L, Chen JS, Simpson JM, Lappe JM, et al. The effects of calcium supplementation on verified coronary heart disease hospitalization and death in postmenopausal women: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Bone Miner Res. 2015; 30:165–175. PMID: 25042841.

Article46. Wang L, Manson JE, Song Y, Sesso HD. Systematic review: vitamin D and calcium supplementation in prevention of cardiovascular events. Ann Intern Med. 2010; 152:315–323. PMID: 20194238.

Article47. Bolland MJ, Grey A, Reid IR. Misclassification does not explain increased cardiovascular risks of calcium supplements. J Bone Miner Res. 2012; 27:959. PMID: 22434645.

Article48. Mao PJ, Zhang C, Tang L, Xian YQ, Li YS, Wang WD, et al. Effect of calcium or vitamin D supplementation on vascular outcomes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Cardiol. 2013; 169:106–111. PMID: 24035175.

Article49. Bolland MJ, Grey A, Avenell A, Reid IR. Calcium supplements increase risk of myocardial infarction. J Bone Miner Res. 2015; 30:389–390. PMID: 25213650.

Article50. Wang L, Manson JE, Sesso HD. Calcium intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: a review of prospective studies and randomized clinical trials. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2012; 12:105–116. PMID: 22283597.51. Larsen ER, Mosekilde L, Foldspang A. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation prevents osteoporotic fractures in elderly community dwelling residents: a pragmatic population-based 3-year intervention study. J Bone Miner Res. 2004; 19:370–378. PMID: 15040824.

Article52. Chung M, Tang AM, Fu Z, Wang DD, Newberry SJ. Calcium intake and cardiovascular disease risk: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2016; 165:856–866. PMID: 27776363.53. Reid IR, Avenell A, Grey A, Bolland MJ. Calcium intake and cardiovascular disease risk. Ann Intern Med. 2017; 166:684–685.

Article54. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Strontium ranelate (Protelos): risk of serious cardiac disorders. Restricted indications, new contraindications, and warnings. Drug Saf Update. 2013; 6:S1.55. Wang X, Chen H, Ouyang Y, Liu J, Zhao G, Bao W, et al. Dietary calcium intake and mortality risk from cardiovascular disease and all causes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Med. 2014; 12:158. PMID: 25252963.

Article56. Tai V, Leung W, Grey A, Reid IR, Bolland MJ. Calcium intake and bone mineral density: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015; 351:h4183. PMID: 26420598.

Article57. Reid IR, Bristow SM, Bolland MJ. Calcium supplements: benefits and risks. J Intern Med. 2015; 278:354–368. PMID: 26174589.

Article58. Bolland MJ, Leung W, Tai V, Bastin S, Gamble GD, Grey A, et al. Calcium intake and risk of fracture: systematic review. BMJ. 2015; 351:h4580. PMID: 26420387.

Article59. Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, Wallace RB, Robbins J, Lewis CE, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354:669–683. PMID: 16481635.60. Lewis JR, Zhu K, Prince RL. Adverse events from calcium supplementation: relationship to errors in myocardial infarction self-reporting in randomized controlled trials of calcium supplementation. J Bone Miner Res. 2012; 27:719–722. PMID: 22139587.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Cardiovascular Impact of Calcium and Vitamin D Supplements: A Narrative Review

- The Risks and Benefits of Calcium Supplementation

- What Plasma Ionized Calcium Concentration Increased by Intravenous Injection with 3% Calcium Chloride and 10 % Calcium Gluconate Is Affected on Cardiovascular System?

- The Relation of Coronary Artery Calcium Scores with Framingham Risk Scores

- Potential of Calcium Scoring CT to Identify Subclinical Coronary Artery Disease in Patients with Prior Thoracic Irradiation