Korean Circ J.

2016 Sep;46(5):719-726. 10.4070/kcj.2016.46.5.719.

Retrospective Multicenter Study of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Prophylaxis in Korean Children with Congenital Heart Diseases

- Affiliations

-

- 1Yonsei University Severance Cardiovascular, Seoul, Korea. jwjung@yuhs.ac

- 2Seoul National University Children's Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Ulsan University Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Gangwon National University, Chuncheon, Korea.

- 5Sungkyunkwan University Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2389631

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2016.46.5.719

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

We conducted a review of current data on respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) prophylaxis with palivizumab, in Korean children with congenital heart diseases (CHD). In 2009, the Korean guideline for RSV prophylaxis had established up to five shots monthly per RSV season, only for children <1 year of age with hemodynamic significance CHD (HS-CHD).

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

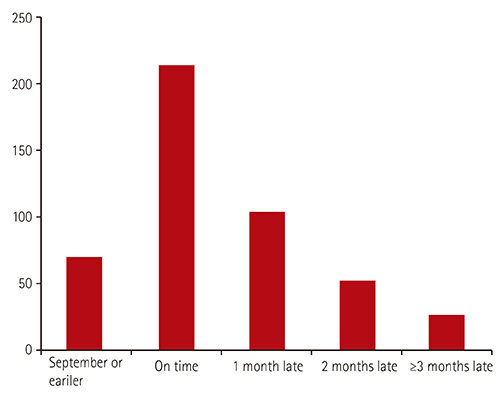

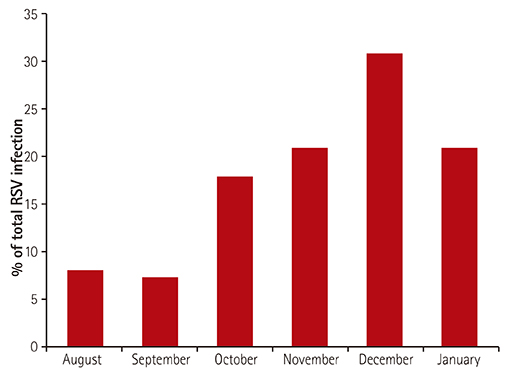

During the RSV seasons in 2009-2015, we performed a retrospective review of data for 466 infants with CHD, examined at six centers in Korea.

RESULTS

Infants received an average of 3.7±1.9 (range, 1-10) injections during the RSV season. Fifty-seven HS-CHD patients (12.2%) were hospitalized with breakthrough RSV bronchiolitis, with a recurrence in three patients, one year after the initial check-up. Among patients with simple CHD, only five (1.1%) patients received one additional dose postoperatively, as per the limitations set by the Korean guideline. Among the 30 deaths (6.4%), five (1.1%) were attributed to RSV infection; three to simple CHD, one to Tetralogy of Fallot, and one to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Of the three HCM patients that exceeded guidelines for RSV prophylaxis, two (66.6%) were hospitalized, and one died of RSV infection (33.3%).

CONCLUSION

In accordance to the Korean guideline, minimal injections of palivizumab were administered to patients having HS-CHD

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Schanzer DL, Langley JM, Tam TW. Hospitalization attributable to influenza and other viral respiratory illnesses in Canadian children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006; 25:795–800.2. Nair H, Nokes DJ, Gessner BD, et al. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010; 375:1545–1555.3. Welliver RC. Review of epidemiology and clinical risk factors for severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection. J Pediatr. 2003; 143:5 Suppl. S112–S117.4. Altman CA, Englund JA, Demmler G, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus in patients with congenital heart disease: a contemporary look at epidemiology and success of preoperative screening. Pediatr Cardiol. 2000; 21:433–438.5. Chang RK, Chen AY. Impact of palivizumab on RSV hospitalizations for children with hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010; 31:90–95.6. Cabalka AK. Physiologic risk factors for respiratory viral infections and immunoprophylaxis for respiratory syncytial virus in young children with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004; 23:1 Suppl. S41–S45.7. Feltes TF, Cabalka AK, Meissner HC, et al. Palivizumab prophylaxis reduces hospitalization due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children with hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease. J Pediatr. 2003; 143:532–540.8. Resch B, Michel-Behnke I. Respiratory syncytial virus infections in infants and children with congenital heart disease: update on the evidence of prevention with palivizumab. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2013; 28:85–91.9. Jung JW. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in children with congenital heart disease: global data and interim results of Korean RSV-CHD survey. Korean J Pediatr. 2011; 54:192–196.10. Andabaka T, Nickerson JW, Rojas-Reyes MX, Rueda JD, Bacic Vrca V, Barsic B. Monoclonal antibody for reducing the risk of respiratory syncytial virus infection in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; 4:CD006602.11. Feltes TF, Sondheimer HM, Tulloh RM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of motavizumab versus palivizumab for the prophylaxis of serious respiratory syncytial virus disease in children with hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease. Pediatr Res. 2011; 70:186–191.12. Yount LE, Mahle WT. Economic analysis of palivizumab in infants with congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2004; 114:1606–1611.13. Meissner HC, Long SS. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases and Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Revised indications for the use of palivizumab and respiratory syncytial virus immune globulin intravenous for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infections. Pediatrics. 2003; 112(6 Pt 1):1447–1452.14. Shim WS, Lee JY, Song JY, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection cases in congenital heart disease patients. Korean J Pediatr. 2010; 53:380–391.15. Saji T, Nakazawa M, Harada K. Nationwide survey of palivizumab for respiratory syncytial virus prevention in Japanese children with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008; 27:1108–1109.16. Rackham OJ, Thorburn K, Kerr SJ. The potential impact of prophylaxis against bronchiolitis due to the respiratory syncytial virus in children with congenital cardiac malformations. Cardiol Young. 2005; 15:251–255.17. Feltes TF, Sondheimer HM. Palivizumab and the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus illness in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2007; 7:1471–1480.18. Butt M, Symington A, Janes M, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus prophylaxis in children with cardiac disease: a retrospective single-centre study. Cardiol Young. 2014; 24:337–343.19. Medrano López C, García-Guereta L. CIVIC Study Group. Community-acquired respiratory infections in young children with congenital heart diseases in the palivizumab era: the Spanish 4-season civic epidemiologic study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010; 29:1077–1082.20. Alexander PM, Eastaugh L, Royle J, Daley AJ, Shekerdemian LS, Penny DJ. Respiratory syncytial virus immunoprophylaxis in high-risk infants with heart disease. J Paediatr Child Health. 2012; 48:395–401.21. Cohen SA, Zanni R, Cohen A, et al. Palivizumab use in subjects with congenital heart disease: results from the 2000-2004 Palivizumab Outcomes Registry. Pediatr Cardiol. 2008; 29:382–387.22. Mitchell I, Paes BA, Li A, Lanctôt KL. CARESS investigators. CARESS: the Canadian registry of palivizumab. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011; 30:651–655.23. Granbom E, Fernlund E, Sunnegårdh J, Lundell B, Naumburg E. Evaluating national guidelines for the prophylactic treatment of respiratory syncytial virus in children with congenital heart disease. Acta Paediatr. 2014; 103:840–845.24. Parnes C, Guillermin J, Habersang R, et al. Palivizumab prophylaxis of respiratory syncytial virus disease in 2000-2001: results from The Palivizumab Outcomes Registry. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003; 35:484–489.25. Golombek SG, Berning F, Lagamma EF. Compliance with prophylaxis for respiratory syncytial virus infection in a home setting. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004; 23:318–322.26. Khongphatthanayothin A, Wong PC, Samara Y, et al. Impact of respiratory syncytial virus infection on surgery for congenital heart disease: postoperative course and outcome. Crit Care Med. 1999; 27:1974–1981.27. Moler FW, Khan AS, Meliones JN, Custer JR, Palmisano J, Shope TC. Respiratory syncytial virus morbidity and mortality estimates in congenital heart disease patients: a recent experience. Crit Care Med. 1992; 20:1406–1413.28. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases. American Academy of Pediatrics Bronchiolitis Guidelines Committee. Updated guidance for palivizumab prophylaxis among infants and young children at increased risk of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection. Pediatrics. 2014; 134:415–420.29. Chantepie A. bureau de la Filiale de Cardiologie Pédiatrique de la Société Française de Cardiologie. Use of palivizumab for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infections in children with congenital heart disease. Recommendations from the French Paediatric Cardiac Society. Arch Pediatr. 2004; 11:1402–1405.30. Kristensen K, Stensballe LG, Bjerre J, et al. Risk factors for respiratory syncytial virus hospitalisation in children with heart disease. Arch Dis Child. 2009; 94:785–789.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Respiratory syncytial virus prevention in children with congenital heart disease: who and how?

- Outcomes of Palivizumab Prophylaxis for Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Preterm Children with Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia at a Single Hospital in Korea from 2005 to 2009

- In Hot Pursuit of the First Vaccine Against Respiratory Syncytial Virus

- Respiratory syncytial virus infection in children with congenital heart disease: global data and interim results of Korean RSV-CHD survey

- Recovery of respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, influenza virus , and parainfluenza virus from nasopharyngeal aspirates from children with acute respiratory tract infections