Restor Dent Endod.

2017 Aug;42(3):240-252. 10.5395/rde.2017.42.3.240.

Management of large class II lesions in molars: how to restore and when to perform surgical crown lengthening?

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Endodontics, University of Santiago de Compostela Facultad de OdontologÃa, Santiago de Compostela, Spain. dablanca.91@gmail.com

- KMID: 2386778

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2017.42.3.240

Abstract

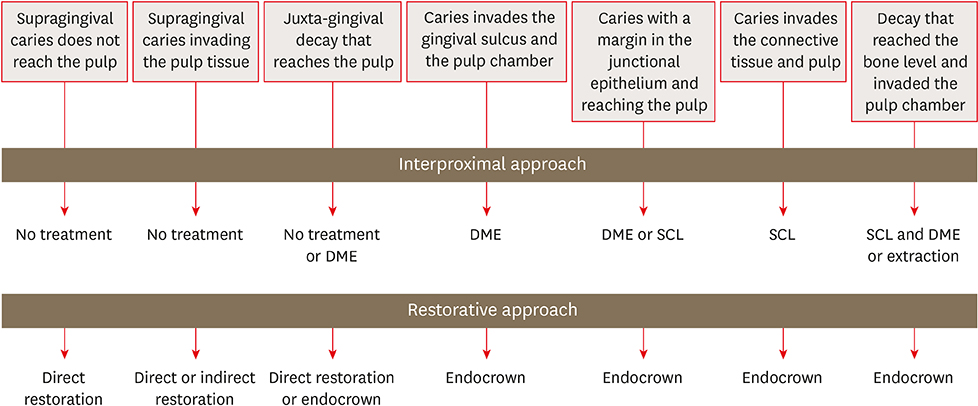

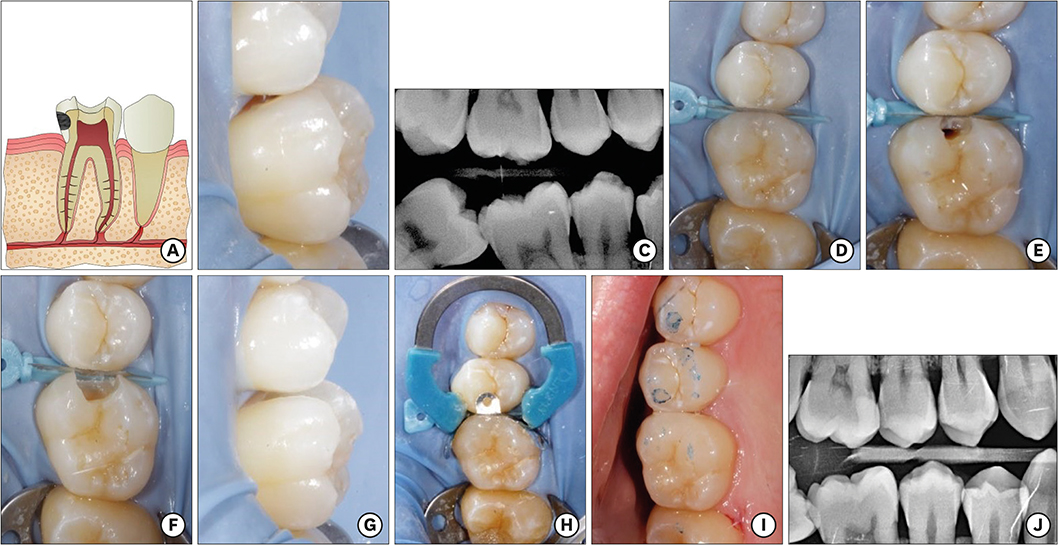

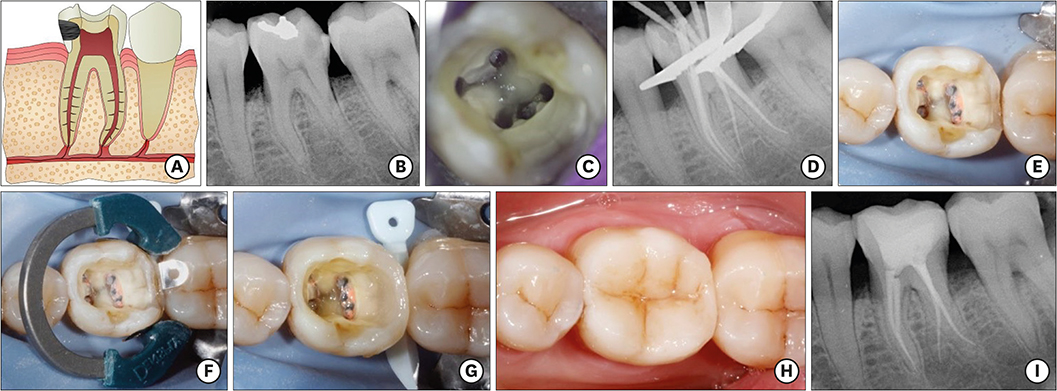

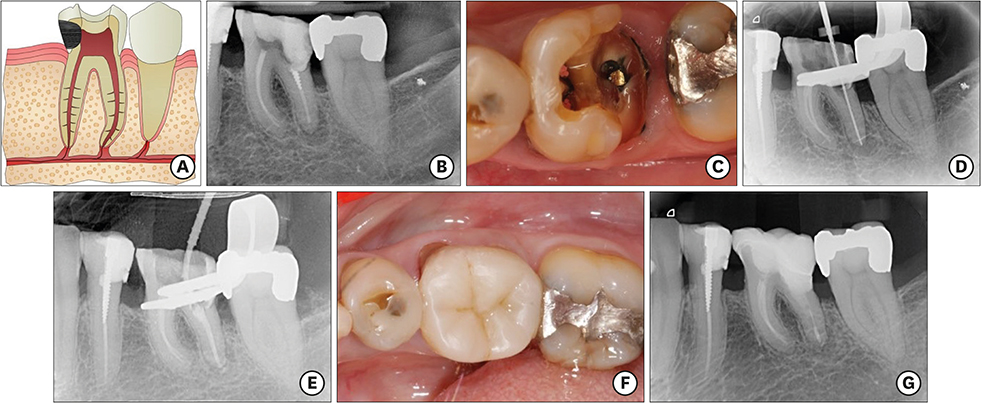

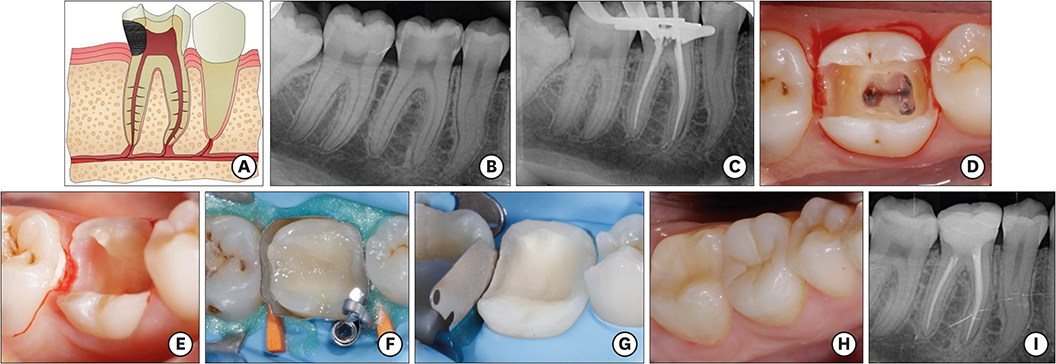

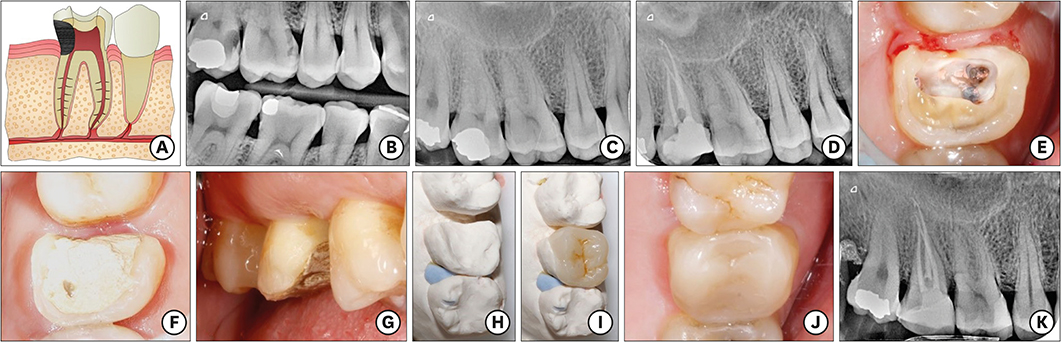

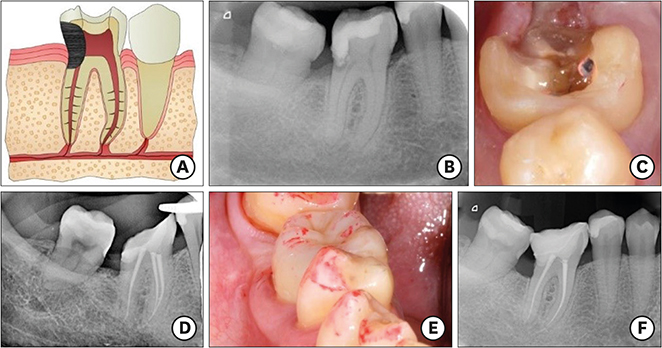

- The restoration of endodontic tooth is always a challenge for the clinician, not only due to excessive loss of tooth structure but also invasion of the biological width due to large decayed lesions. In this paper, the 7 most common clinical scenarios in molars with class II lesions ever deeper were examined. This includes both the type of restoration (direct or indirect) and the management of the cavity margin, such as the need for deep margin elevation (DME) or crown lengthening. It is necessary to have the DME when the healthy tooth remnant is in the sulcus or at the epithelium level. For caries that reaches the connective tissue or the bone crest, crown lengthening is required. Endocrowns are a good treatment option in the endodontically treated tooth when the loss of structure is advanced.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Padbury A Jr, Eber R, Wang HL. Interactions between the gingiva and the margin of restorations. J Clin Periodontol. 2003; 30:379–385.

Article2. Sedgley CM, Messer HH. Are endodontically treated teeth more brittle? J Endod. 1992; 18:332–335.

Article3. Fichera G, Devoto W, Re D. Cavity configurations for indirect partial-coverage adhesive-cemented restorations. Quintessence Dent Technol. 2006; 29:55–67.4. Veneziani M. Adhesive restorations in the posterior area with subgingival cervical margins: new classification and differentiated treatment approach. Eur J Esthet Dent. 2010; 5:50–76.5. Magne P, Spreafico RC. Deep margin elevation: a paradigm shift. Am J Esthet Dent. 2012; 2:86–96.6. García Barbero J. Pathology and dental therapeutics: operative dentistry and endodontics. 2nd ed. Barcelona: Elsevier;2015. p. 341–351.7. Asgary S, Fazlyab M, Sabbagh S, Eghbal MJ. Outcomes of different vital pulp therapy techniques on symptomatic permanent teeth: a case series. Iran Endod J. 2014; 9:295–300.8. Dietschi D, Duc O, Krejci I, Sadan A. Biomechanical considerations for the restoration of endodontically treated teeth: a systematic review of the literature, part II (evaluation of fatigue behavior, interfaces, and in vivo studies). Quintessence Int. 2008; 39:117–129.9. Plotino G, Buono L, Grande NM, Lamorgese V, Somma F. Fracture resistance of endodontically treated molars restored with extensive composite resin restorations. J Prosthet Dent. 2008; 99:225–232.

Article10. Biacchi GR, Mello B, Basting RT. The endocrown: an alternative approach for restoring extensively damaged molars. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2013; 25:383–390.

Article11. Linn J, Messer HH. Effect of restorative procedures on the strength of endodontically treated molars. J Endod. 1994; 20:479–485.

Article12. Planciunas L, Puriene A, Mackeviciene G. Surgical lengthening of the clinical tooth crown. Stomatologija. 2006; 8:88–95.13. Magne P, Belser U. Bonded porcelain restorations in the anterior dentition: a biomimetic approach. Chicago (IL): Quintessence;2002. p. 23–25.14. Magne P, Knezevic A. Influence of overlay restorative materials and load cusps on the fatigue resistance of endodontically treated molars. Quintessence Int. 2009; 40:729–737.15. Lander E, Dietschi D. Endocrowns: a clinical report. Quintessence Int. 2008; 39:99–106.16. Dietschi D, Bouillaguet S, Sadan A. Restoration of the endodontically treated tooth. In : Hargreaves KM, Cohen S, Berman LH, editors. Cohen's pathways of the pulp. 10th ed. St. Louis (MA): Mosby Elsevier;2011. p. 777–807.17. Robbins JW. Restoration of the endodontically treated tooth. Dent Clin North Am. 2002; 46:367–384.

Article18. Bindl A, Mörmann WH. Clinical evaluation of adhesively placed Cerec endo-crowns after 2 years--preliminary results. J Adhes Dent. 1999; 1:255–265.19. Rocca GT, Rizcalla N, Krejci I, Dietschi D. Evidence-based concepts and procedures for bonded inlays and onlays. Part II. Guidelines for cavity preparation and restoration fabrication. Int J Esthet Dent. 2015; 10:392–413.20. Santos-Filho PC, Veríssimo C, Raposo LH. Noritomi MecEng PY, Marcondes Martins LR. Influence of ferrule, post system, and length on stress distribution of weakened root-filled teeth. J Endod. 2014; 40:1874–1878.

Article21. Boyle WD Jr, Via WF Jr, McFall WT Jr. Radiographic analysis of alveolar crest height and age. J Periodontol. 1973; 44:236–243.

Article22. Mishkin DJ, Gellin RG. Re: Biologic width and crown lengthening. J Periodontol. 1993; 64:920.23. Martins TM, Bosco AF, Nóbrega FJ, Nagata MJ, Garcia VG, Fucini SE. Periodontal tissue response to coverage of root cavities restored with resin materials: a histomorphometric study in dogs. J Periodontol. 2007; 78:1075–1082.

Article24. Pama-Benfenati S, Fugazzotto PA, Ferreira PM, Ruben MP, Kramer GM. The effect of restorative margins on the postsurgical development and nature of the periodontium. Part II. Anatomical considerations. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1986; 6:64–75.25. Block PL. Restorative margins and periodontal health: a new look at an old perspective. J Prosthet Dent. 1987; 57:683–689.

Article26. Lee JH, Yoon SM. Surgical extrusion of multiple teeth with crown-root fractures: a case report with 18-months follow up. Dent Traumatol. 2015; 31:150–155.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Considerations in the selection of method for clinical crown lengthening

- A study on the calcification of second molars in skeletal Class II malocclusion

- A study of the calcification of the second and the third molars in skeletal Class II and III malocclusions

- Full mouth rehabilitation of partially and fully edentulous patient with crown lengthening procedure: a case report

- Clinical crown lengthening procedure using surgical extrusion in esthetic region