Ann Lab Med.

2017 Jan;37(1):53-57. 10.3343/alm.2017.37.1.53.

Fecal Calprotectin Level Reflects the Severity of Clostridium difficile Infection

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Laboratory Medicine and Research Institute of Bacterial Resistance, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. deyong@yuhs.ac

- 2Brain Korea 21 PLUS Project for Medical Science, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2373614

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3343/alm.2017.37.1.53

Abstract

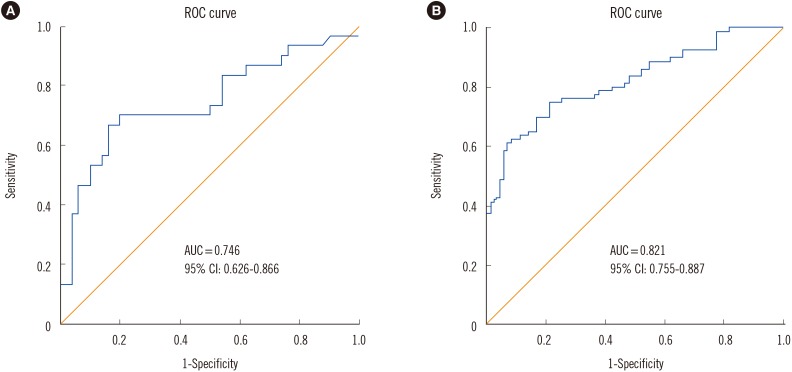

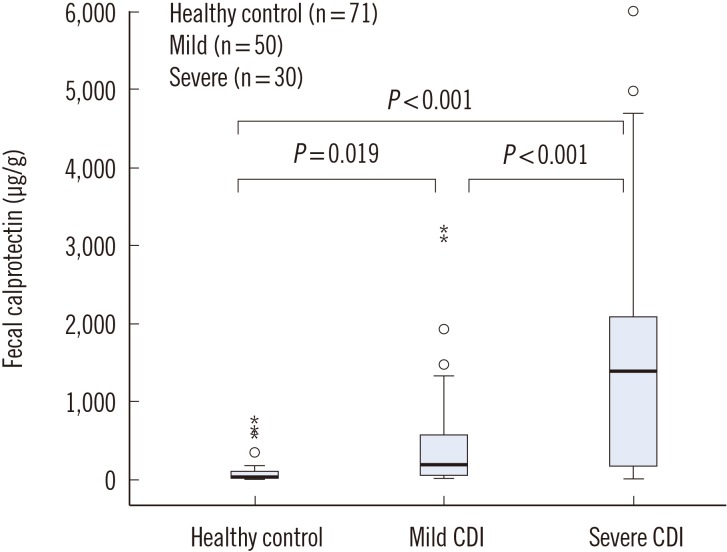

- Clostridium difficile is a significant nosocomial and community-acquired pathogen, and is the leading cause of antibiotic-induced diarrhea associated with high morbidity and mortality. Given that the treatment outcome depends on the severity of C. difficile infection (CDI), we aimed to establish an efficient method of assessing severity, and focused on the stool biomarker fecal calprotectin (FC). FC directly reflects the intestinal inflammation status of a patient, and can aid in interpreting the current guidelines, which requires the integration of indirect laboratory parameters. The distinction of 80 patients with CDI versus 71 healthy controls and 30 severe infection cases versus 50 mild cases was possible using FC as a marker. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curves were 0.821 and 0.746 with a sensitivity of 75% and 70% and specificity of 79% and 80%, for severe versus mild cases, respectively. We suggest FC as a predictive marker for assessing CDI severity, which is expected to improve the clinical management of CDI.

MeSH Terms

-

Aged

Area Under Curve

Biomarkers/analysis

Clostridium difficile/*isolation & purification

Enterocolitis, Pseudomembranous/diagnosis/microbiology/*pathology

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Feces/*chemistry

Female

Humans

Leukocyte L1 Antigen Complex/*analysis

Male

Middle Aged

ROC Curve

Severity of Illness Index

Biomarkers

Leukocyte L1 Antigen Complex

Figure

Reference

-

1. Kim YA, Rim JH, Choi MH, Kim H, Lee K. Increase of Clostridium difficile in community; another worrisome burden for public health. Ann Clin Microbiol. 2016; 19:7–12.2. Poutanen SM, Simor AE. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults. CMAJ. 2004; 171:51–58. PMID: 15238498.3. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Kelly CP, Loo VG, McDonald LC, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010; 31:431–455. PMID: 20307191.4. Debast SB, Bauer MP, Kuijper EJ. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: update of the treatment guidance document for Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014; 20(S2):1–26.5. Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, Ananthakrishnan AN, Curry SR, Gilligan PH, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013; 108:478–498. quiz 499. PMID: 23439232.6. Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, Davis MB. A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 45:302–307. PMID: 17599306.7. Aradhyula S, Manian FA, Hafidh SA, Bhutto SS, Alpert MA. Significant absorption of oral vancomycin in a patient with Clostridium difficile colitis and normal renal function. South Med J. 2006; 99:518–520. PMID: 16711316.8. Kim H, Kim WH, Kim M, Jeong SH, Lee K. Evaluation of a rapid membrane enzyme immunoassay for the simultaneous detection of glutamate dehydrogenase and toxin for the diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection. Ann Lab Med. 2014; 34:235–239. PMID: 24790912.9. Boone JH, DiPersio JR, Tan MJ, Salstrom SJ, Wickham KN, Carman RJ, et al. Elevated lactoferrin is associated with moderate to severe Clostridium difficile disease, stool toxin, and 027 infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013; 32:1517–1523. PMID: 23771554.10. El Feghaly RE, Stauber JL, Deych E, Gonzalez C, Tarr PI, Haslam DB. Markers of intestinal inflammation, not bacterial burden, correlate with clinical outcomes in Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2013; 56:1713–1721. PMID: 23487367.11. Shastri YM, Bergis D, Povse N, Schäfer V, Shastri S, Weindel M, et al. Prospective multicenter study evaluating fecal calprotectin in adult acute bacterial diarrhea. Am J Med. 2008; 121:1099–1106. PMID: 19028207.12. Lee KM. Fecal biomarkers in inflammatory bowel disease. Intest Res. 2013; 11:73–78.13. Steinbakk M, Naess-Andresen CF, Lingaas E, Dale I, Brandtzaeg P, Fagerhol MK. Antimicrobial actions of calcium binding leucocyte L1 protein, calprotectin. Lancet. 1990; 336:763–765. PMID: 1976144.14. Caccaro R, D'Incá R, Sturniolo GC. Clinical utility of calprotectin and lactoferrin as markers of inflammation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2010; 6:551–558. PMID: 20594128.15. Whitehead SJ, Shipman KE, Cooper M, Ford C, Gama R. Is there any value in measuring faecal calprotectin in Clostridium difficile positive faecal samples? J Med Microbiol. 2014; 63:590–593. PMID: 24464697.16. van Rheenen PF, Van de Vijver E, Fidler V. Faecal calprotectin for screening of patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease: diagnostic meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010; 341:c3369. PMID: 20634346.17. Leekha S, Terrell CL, Edson RS. General principles of antimicrobial therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011; 86:156–167. PMID: 21282489.18. Crobach MJ, Dekkers OM, Wilcox MH, Kuijper EJ. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID): data review and recommendations for diagnosing Clostridium difficile-infection (CDI). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009; 15:1053–1066. PMID: 19929972.19. Waugh N, Cummins E, Royle P, Kandala NB, Shyangdan D, Arasaradnam R, et al. systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2013; 17:xv–xix. 1–211. PMID: 24286461.20. Swale A, Miyajima F, Roberts P, Hall A, Little M, Beadsworth MB, et al. Calprotectin and lactoferrin faecal levels in patients with Clostridium difficile infection (CDI): a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e106118. PMID: 25170963.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Clinical Utility of Fecal Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin and Calprotectin as Biomarkers of Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile Infection

- Refractory Clostridium difficile Infection Cured With Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus Colonized Patient

- A Case of Toxic Megacolon Caused by Clostridium difficile Infection and Treated with Fecal Microbiota Transplantation

- Fecal Microbiota Transplantation as a Treatment of Recurrent Clostridium difficile Infection: Where Are We Now and Where Are We Heading?

- Clostridium difficile Infection: What's New?