Korean J Crit Care Med.

2017 Feb;32(1):9-21. 10.4266/kjccm.2016.00969.

Management of Critical Burn Injuries: Recent Developments

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Surgery and Anesthesiology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA. david.j.dries@healthpartners.com

- 2Department of Medicine, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA.

- KMID: 2371149

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4266/kjccm.2016.00969

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Burn injury and its subsequent multisystem effects are commonly encountered by acute care practitioners. Resuscitation is the major component of initial burn care and must be managed to restore and preserve vital organ function. Later complications of burn injury are dominated by infection. Burn centers are often called to manage problems related to thermal injury, including lightning and electrical injuries.

METHODS

A selected review is provided of key management concepts as well as of recent reports published by the American Burn Association.

RESULTS

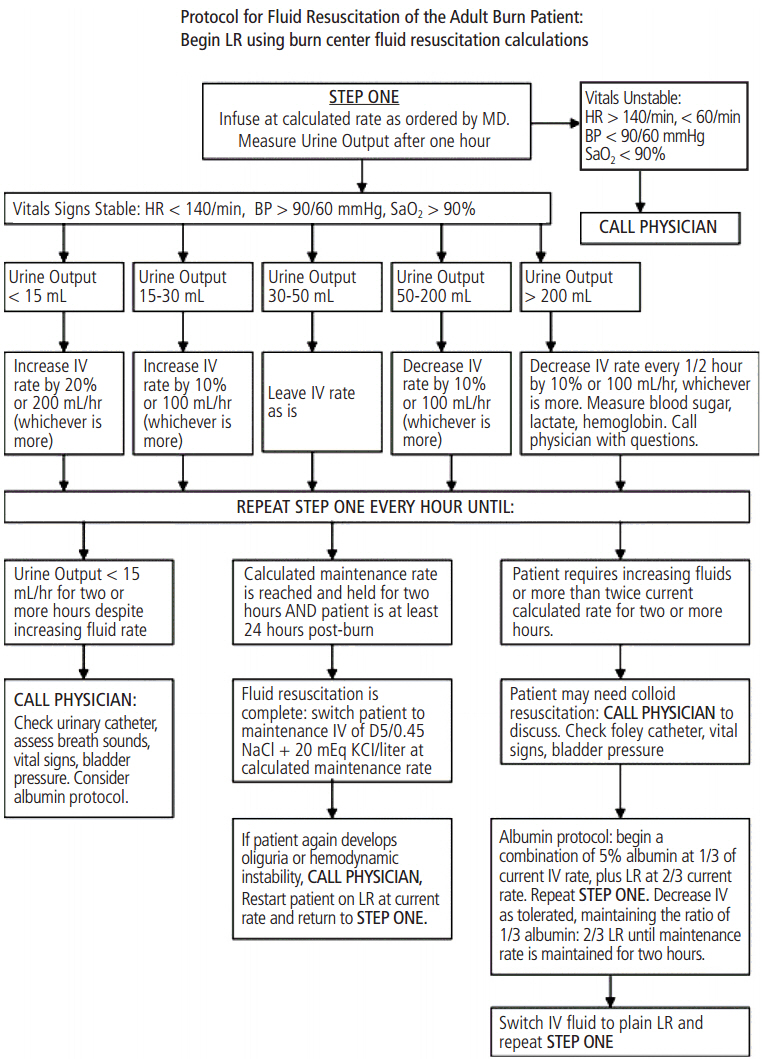

The burn-injured patient is easily and frequently over resuscitated, with ensuing complications that include delayed wound healing and respiratory compromise. A feedback protocol designed to limit the occurrence of excessive resuscitation has been proposed, but no new "gold standard" for resuscitation has replaced the venerated Parkland formula. While new medical therapies have been proposed for patients sustaining inhalation injury, a paradigm-shifting standard of medical therapy has not emerged. Renal failure as a specific contributor to adverse outcome in burns has been reinforced by recent data. Of special problems addressed in burn centers, electrical injuries pose multisystem physiologic challenges and do not fit typical scoring systems.

CONCLUSION

Recent reports emphasize the dangers of over resuscitation in the setting of burn injury. No new medical therapy for inhalation injury has been generally adopted, but new standards for description of burn-related infections have been presented. The value of the burn center in care of the problems of electrical exposure, both manmade and natural, is demonstrated in recent reports.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Latenser BA. Critical care of the burn patient: the first 48 hours. Crit Care Med. 2009; 37:2819–26.

Article2. Baxter CR. Fluid volume and electrolyte changes of the early postburn period. Clin Plast Surg. 1974; 1:693–703.

Article3. Saffle JR. The phenomenon of “fluid creep” in acute burn resuscitation. J Burn Care Res. 2007; 28:382–95.

Article4. Pham TN, Cancio LC, Gibran NS; American Burn Association. American Burn Association practice guidelines burn shock resuscitation. J Burn Care Res. 2008; 29:257–66.

Article5. Blumetti J, Hunt JL, Arnoldo BD, Parks JK, Purdue GF. The Parkland formula under fire: is the criticism justified? J Burn Care Res. 2008; 29:180–6.

Article6. Greenhalgh DG, Saffle JR, Holmes JH 4th, Gamelli RL, Palmieri TL, Horton JW, et al. American Burn Association consensus conference to define sepsis and infection in burns. J Burn Care Res. 2007; 28:776–90.

Article7. Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Doig GS, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA. 2005; 294:813–8.8. Koumbourlis AC. Electrical injuries. Crit Care Med. 2002; 30(11 Suppl):S424–30.

Article9. Ivy ME, Atweh NA, Palmer J, Possenti PP, Pineau M, D’Aiuto M. Intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome in burn patients. J Trauma. 2000; 49:387–91.

Article10. Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992; 101:1644–55.11. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, et al. Surviving sepsis guidelines: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013; 41:580–637.12. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016; 315:801–10.

Article13. Hubmayr RD, Burchardi H, Elliot M, Fessler H, Georgopoulos D, Jubran A, et al. Statement of the 4th international consensus conference in critical care on ICU-acquired pneumonia--Chicago, Illinois, May 2002. Intensive Care Med. 2002; 28:1521–36.14. Rello J, Paiva JA, Baraibar J, Barcenilla F, Bodi M, Castander D, et al. International conference for the development of consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2001; 120:955–70.

Article15. Mosier MJ, Pham TN. American Burn Association practice guidelines for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) in burn patients. J Burn Care Res. 2009; 30:910–28.

Article16. Sen S, Johnston C, Greenhalgh D, Palmieri T. Ventilator-associated pneumonia prevention bundle significantly reduces the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill burn patients. J Burn Care Res. 2016; 37:166–71.

Article17. Chung KK, Rhie RY, Lundy JB, Cartotto R, Henderson E, Pressman MA, et al. A survey of mechanical ventilator practices across burn centes in North America. J Burn Care Res. 2016; 37:e131–9.18. Peck MD, Weber J, McManus A, Sheridan R, Heimbach D. Surveillance of burn wound infections: a proposal for definitions. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1998; 19:386–9.

Article19. Arnoldo BD, Purdue GF, Kowalske K, Helm PA, Burris A, Hunt JL. Electrical injuries: a 20-year review. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2004; 25:479–84.

Article20. Lichtenberg R, Dries D, Ward K, Marshall W, Scanlon P. Cardiovascular effects of lightning strikes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993; 21:531–6.

Article21. Arnoldo B, Klein M, Gibran NS. Practice guidelines for the management of electrical injuries. J Burn Care Res. 2006; 27:439–47.

Article22. Singerman J, Gomez M, Fish JS. Long-term sequelae of low-voltage electrical injury. J Burn Care Res. 2008; 29:773–7.

Article23. ARDS Definition Task Force, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012; 307:2526–33.24. Dries DJ, Endorf FW. Inhalation injury: epidemiology, pathology, treatment strategies. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2013; 21:31.

Article25. Jeng JC. Patrimonie de Docteur Baux--Baux Scores >> 100 gleaned from 170,791 admissions: a glimmer from the National Burn repository. J Burn Care Res. 2007; 28:380–1.26. American Burn Association. 2016 National Burn Repository. Report of data from 2006-2015 [Internet]. Chicago: American Burn Association;c2017. [cited 2017 Jan 12]. Available from: www.ameriburn.org/NBR.php.27. Ryan CM, Schoenfeld DA, Thorpe WP, Sheridan RL, Cassem EH, Tompkins RG. Objective estimates of the probability of death from burn injuries. N Engl J Med. 1998; 338:362–6.

Article28. Paratz JD, Lipman J, Boots RJ, Muller MJ, Paterson DL. A new marker for sepsis post burn injury?*. Crit Care Med. 2014; 42:2029–36.29. Yang HT, Yim H, Cho YS, Kym D, Hur J, Kim JH, et al. Assessment of biochemical markers in the early post-burn period for predicting acute kidney injury and mortality inpatients with major burn injury: comparison of serum creatinine, serum cystatiC, plasma and urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin. Crit Care. 2014; 18:R151.30. Palmieri TL, London JA, O’Mara MS, Greenhalgh DG. Analysis of admissions and outcomes in verified and nonverified burn centers. J Burn Care Res. 2008; 29:208–12.

Article31. Ehrlich PF, Rockwell S, Kincaid S, Mucha P Jr. American College of Surgeons, Committee on Trauma Verification Review: does it really make a difference? J Trauma. 2002; 53:811–6.

Article32. Sheridan RL. Burn care: results of technical and organizational progress. JAMA. 2003; 290:719–22.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Management of Major Burn Patients with Multiple Rib Fractures: 2 Case Report

- Deep Burn Injuries on the Lower Abdomen after HIFU Treatment for Uterine Myoma

- Roles of the Burn Clinical Nurse Specialist (BCNS) in Burn Center

- Concurrent Two Types of Burn with Airbag in an Upper Extremity: Case Report

- Herpes Zoster Manifestation in the Treatment of a Facial Scald Burn: A Case Report