Korean Circ J.

2017 Jan;47(1):65-71. 10.4070/kcj.2016.0039.

The Role of Intravenous Dopamine on Hemodynamic Support during Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation of Poorly Tolerated Idiopathic Ventricular Tachycardia

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. yhkmd@unitel.co.kr

- KMID: 2365284

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2016.0039

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

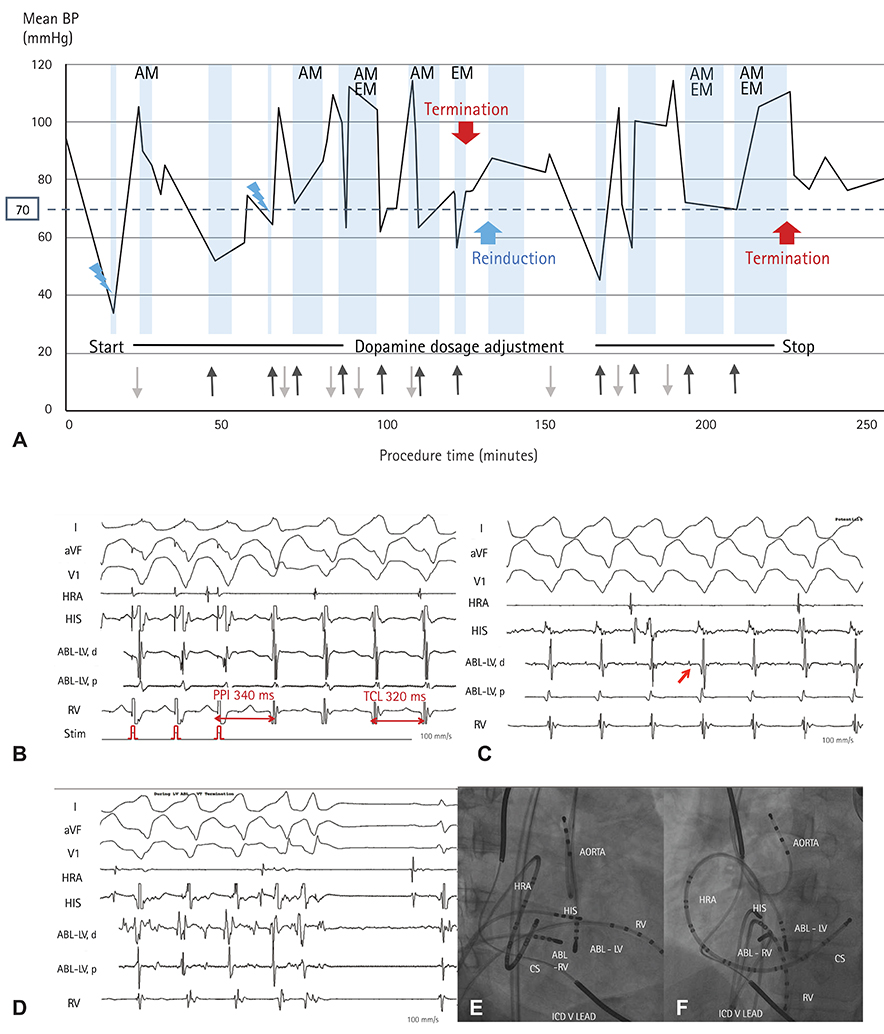

Hemodynamically unstable idiopathic ventricular tachycardias (VTs) are a challenge for activation or entrainment mapping technique. Mechanical circulatory support is an option, but is not always readily available. In this study, we investigated the safety and efficacy of hemodynamic support using intravenous (IV) dopamine solely during radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA) of hemodynamically unstable VT.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Seven out of 86 patients with hemodynamically unstable idiopathic VT underwent de novo RFCA using dopamine in our single center. They were included in the study and reviewed retrospectively to investigate the procedural characteristics and outcomes.

RESULTS

All patients were male, and the mean age was 50.7±5.3 years. One patient had implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for the secondary prevention. No evidence of myocardial ischemia was found in all patients. During the procedure, the mean blood pressure during VT without dopamine was 52.3±4.1 mmHg and increased to 82.6±3.8 mmHg after administering dopamine (Δ28.8±3.2 mmHg; total average dopamine dosage was 1266.1±389.6 mcg/kg). In all patients, activation mapping was safely applied, and VTs were terminated during energy delivery. Non-inducibility of clinical VT was achieved in all cases. There was no evidence of deterioration due to hypoperfusion during the peri-procedural period. No recurrence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias was observed in any of the patients, during a median follow-up of 23.0±6.1 months.

CONCLUSION

Hemodynamic support using IV dopamine during RFCA of hemodynamically unstable idiopathic VT facilitated detailed mapping to guide successful ablation.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Pedersen CT, Kay GN, Kalman J, et al. EHRA/HRS/APHRS Expert consensus on ventricular arrhythmias. Europace. 2014; 16:1257–1283.2. Lü F, Eckman PM, Liao KK, et al. Catheter ablation of hemodynamically unstable ventricular tachycardia with mechanical circulatory support. Int J Cardiol. 2013; 168:3859–3865.3. Aryana A, Gearoid O'Neill P, Gregory D, et al. Procedural and clinical outcomes after catheter ablation of unstable ventricular tachycardia supported by a percutaneous left ventricular assist device. Heart Rhythm. 2014; 11:1122–1130.4. Miller MA, Dukkipati SR, Chinitz JS, et al. Percutaneous hemodynamic support with Impella 2.5 during scar-related ventricular tachycardia ablation (PERMIT 1). Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013; 6:151–159.5. Rizkallah J, Shen S, Tischenko A, Zieroth S, Freed DH, Khadem A. Successful ablation of idiopathic left ventricular tachycardia in an adult patient during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment. Can J Cardiol. 2013; 29:1741.e17–1741.e19.6. Nazer B, Gerstenfeld EP. Catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in patients with post-infarction cardiomyopathy. Korean Circ J. 2014; 44:210–217.7. Marchlinski FE, Callans DJ, Gottlieb CD, Zado E. Linear ablation lesions for control of unmappable ventricular tachycardia in patients with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2000; 101:1288–1296.8. Jais P, Maury P, Khairy P, et al. Elimination of local abnormal ventricular activities. A new end point for substrate modification in patients with scar-related ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2012; 125:2184–2196.9. Vergara P, Trevisi N, Ricco A, et al. Late potentials abolition as an additional technique for reduction of arrhythmia recurrence in scar related ventricular tachycardia ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012; 23:621–627.10. Letsas KP, Charalampous C, Weber R, et al. Methods and indications for ablation of ventricular tachycardia. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2011; 52:427–436.11. Miller MA, Reddy VY. Percutaneous hemodynamic support during scar-ventricular tachycardia ablation: Is the juice worth the squeeze? Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014; 7:192–194.12. Stevenson WG, Soejima K. Catheter ablation for ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2007; 115:2750–2760.13. Issa ZF, Miller JM, Zipes DP. Clinical arrhythmology and electrophysiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier;2012. p. 573–576.14. Tabatabaei N, Asirvatham SJ. Supravalvular arrhythmia. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009; 2:316–326.15. Della Bella P, Baratto F, Tsiachris D, et al. Management of ventricular tachycardia in the setting of a dedicated unit for the treatment of complex ventricular arrhythmias. Circulation. 2013; 127:1359–1368.16. Bunch TJ, Darby A, May HT, et al. Efficacy and safety of ventricular tachycardia ablation with mechanical circulatory support compared with substrate-based ablation techniques. Europace. 2012; 14:709–714.17. Reddy YM, Chinitz L, Mansour M, et al. Percutaneous left ventricular assist devices in ventricular tachycardia ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014; 7:244–250.18. Miller MA, Dukkipati SR, Mittnacht AJ, et al. Activation and entrainment mapping of hemodynamically unstable ventricular tachycardia using a percutaneous left ventricular assist device. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 58:1363–1371.19. Bella PD, Maccabelli G. Temporary percutaneous left ventricular support for ablation of untolerated ventricular tachycardias. Is it worth the trouble? Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012; 5:1056–1058.20. Tisdale JE, Patel R, Webb CR, Borzak S, Zarowitz BJ. Electrophysiologic and proarrhythmic effects of intravenous inotropic agents. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1995; 38:167–180.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia in Patients without Structural Heart Disease

- Successful Treatment of Tachycardia-induced Cardiomyopathy with Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation

- Catheter ablation for treatment of tachyarrhythmia

- Successful Control of Double Tarchycardia Using Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation

- Mid-Septal Hypertrophy and Apical Ballooning; Potential Mechanism of Ventricular Tachycardia Storm in Patients with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy