Yonsei Med J.

2015 Nov;56(6):1613-1618. 10.3349/ymj.2015.56.6.1613.

Idiom Comprehension Deficits in High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder Using a Korean Autism Social Language Task

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry and Institute of Behavioral Science in Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. kacheon@yuhs.ac

- 2Department of Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2345890

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2015.56.6.1613

Abstract

- PURPOSE

High-functioning autism spectrum disorder (ASD) involves pragmatic impairment of language skills. Among numerous tasks for assessing pragmatic linguistic skills, idioms are important to evaluating high-functioning ASD. Nevertheless, no assessment tool has been developed with specific consideration of Korean culture. Therefore, we designed the Korean Autism Social Language Task (KASLAT) to test idiom comprehension in ASD. The aim of the current study was to introduce this novel psychological tool and evaluate idiom comprehension deficits in high-functioning ASD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The participants included 42 children, ages 6-11 years, who visited our child psychiatric clinic between April 2014 and May 2015. The ASD group comprised 16 children; the attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) group consisted of 16 children. An additional 10 normal control children who had not been diagnosed with either disorder participated in this study. Idiom comprehension ability was assessed in these three groups using the KASLAT.

RESULTS

Both ASD and ADHD groups had significantly lower scores on the matched and mismatched tasks, compared to the normal control children (matched tasks mean score: ASD 11.56, ADHD 11.56, normal control 14.30; mismatched tasks mean score: ASD 6.50, ADHD 4.31, normal control 11.30). However, no significant differences were found in scores of KASLAT between the ADHD and ASD groups.

CONCLUSION

These findings suggest that children with ASD exhibit greater impairment in idiom comprehension, compared to normal control children. The KASLAT may be useful in evaluating idiom comprehension ability.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

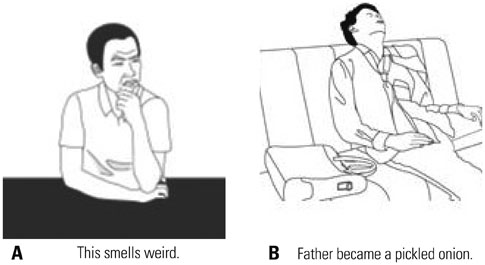

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Aberrant Neural Activation Underlying Idiom Comprehension in Korean Children with High Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder

Namwook Kim, Uk-Su Choi, Sungji Ha, Seul Bee Lee, Seung Ha Song, Dong Ho Song, Keun-Ah Cheon

Yonsei Med J. 2018;59(7):897-903. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2018.59.7.897.

Reference

-

1. Morey LC, Bender DS, Skodol AE. Validating the proposed diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition, severity indicator for personality disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013; 201:729–735.2. Brook SL, Bowler DM. Autism by another name? Semantic and pragmatic impairments in children. J Autism Dev Disord. 1992; 22:61–81.3. Baron-Cohen S. Social and pragmatic deficits in autism: cognitive or affective? J Autism Dev Disord. 1988; 18:379–402.4. Myles BS, Hilgenfeld TD, Barnhill GP, Griswold DE, Hagiwara T, Simpson RL. Analysis of reading skills in individuals with Asperger syndrome. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabil. 2002; 17:44–47.

Article5. Wahlberg T, Magliano JP. The ability of high function individuals with autism to comprehend written discourse. Discourse Process. 2004; 38:119–144.

Article6. Rapin I, Dunn M. Update on the language disorders of individuals on the autistic spectrum. Brain Dev. 2003; 25:166–172.

Article7. Bates E. Language and context: Studies in the acquisition of pragmatics. Chicago: University of Chicago, Committee on Human Development;1974.8. Levorato MC, Cacciari C. Children's comprehension and production of idioms: the role of context and familiarity. J Child Lang. 1992; 19:415–433.

Article9. Wiig EH, Secord W. Test of Language Competence (TLC), Expanded Edition. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation;1989.10. Happé FG. Communicative competence and theory of mind in autism: a test of relevance theory. Cognition. 1993; 48:101–119.

Article11. Kerbel D, Grunwell P. A study of idiom comprehension in children with semantic-pragmatic difficulties. Part II: Between-groups results and discussion. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 1998; 33:23–44.

Article12. Ozonoff S, Miller JN. An exploration of right-hemisphere contributions to the pragmatic impairments of autism. Brain Lang. 1996; 52:411–434.

Article13. Happé FG. Understanding minds and metaphors: insights from the study of figurative language in autism. Metaphor Symb Act. 1995; 10:275–295.

Article14. Dennis M, Lazenby AL, Lockyer L. Inferential language in high-function children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001; 31:47–54.15. Choi KJ. The study of Metaphor. Metonymy of Korean Pragmatics;2010.16. Attwood T. Asperger's syndrome: a guide for parents and professionals. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers;1997.17. Nippold MA, Martin ST. Idiom interpretation in isolation versus context: a developmental study with adolescents. J Speech Hear Res. 1989; 32:59–66.18. Levorato MC, Cacciari C. Idiom comprehension in children: are the effects of semantic analysability and context separable? Eur J Cogn Psychol. 1999; 11:51–66.19. Rescorla L, Mirak J. Normal language acquisition. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 1997; 4:70–76.20. Paul R. Language disorders from infancy through adolescence: assessment and intervention. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Health Sciences;2007.21. Silagi ML, Romero VU, Mansur LL, Radanovic M. Inference comprehension during reading: influence of age and education in normal adults. Codas. 2014; 26:407–414.

Article22. Seol KI, Song SH, Kim KL, Oh ST, Kim YT, Im WY, et al. A comparison of receptive-expressive language profiles between toddlers with autism spectrum disorder and developmental language delay. Yonsei Med J. 2014; 55:1721–1728.23. Rapin I, Dunn M. Language disorders in children with autism. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 1997; 4:86–92.

Article24. Camarata SM, Gibson T. Pragmatic language deficits in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 1999; 5:207–214.

Article25. Nigg JT. The ADHD response-inhibition deficit as measured by the stop task: replication with DSM-IV combined type, extension, and qualification. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1999; 27:393–402.26. Aman CJ, Roberts RJ Jr, Pennington BF. A neuropsychological examination of the underlying deficit in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: frontal lobe versus right parietal lobe theories. Dev Psychol. 1998; 34:956–969.

Article27. Oosterlaan J, Logan GD, Sergeant JA. Response inhibition in AD/HD, CD, comorbid AD/HD + CD, anxious, and control children: a meta-analysis of studies with the stop task. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1998; 39:411–425.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Aberrant Neural Activation Underlying Idiom Comprehension in Korean Children with High Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Clinical Implications of Social Communication Disorder

- The Relationship of Clinical Symptoms with Social Cognition in Children Diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Specific Learning Disorder or Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Environmental Factors in Autism and Autistic Spectrum Disorder

- Comparison of the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule and Childhood Autism Rating Scale in the Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Preliminary Study