Cancer Res Treat.

2016 Jul;48(3):1010-1019. 10.4143/crt.2015.279.

Cost Effectiveness of Colorectal Cancer Screening Interventions with Their Effects on Health Disparity Being Considered

- Affiliations

-

- 1Health Insurance Policy Research Institute, Korea National Health Insurance Service, Wonju, Korea.

- 2Department of Preventive Medicine and Institute of Health Services Research, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea. ecpark@yuhs.ac

- KMID: 2344074

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2015.279

Abstract

- PURPOSE

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the cost effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening interventions with their effects on health disparity being considered.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

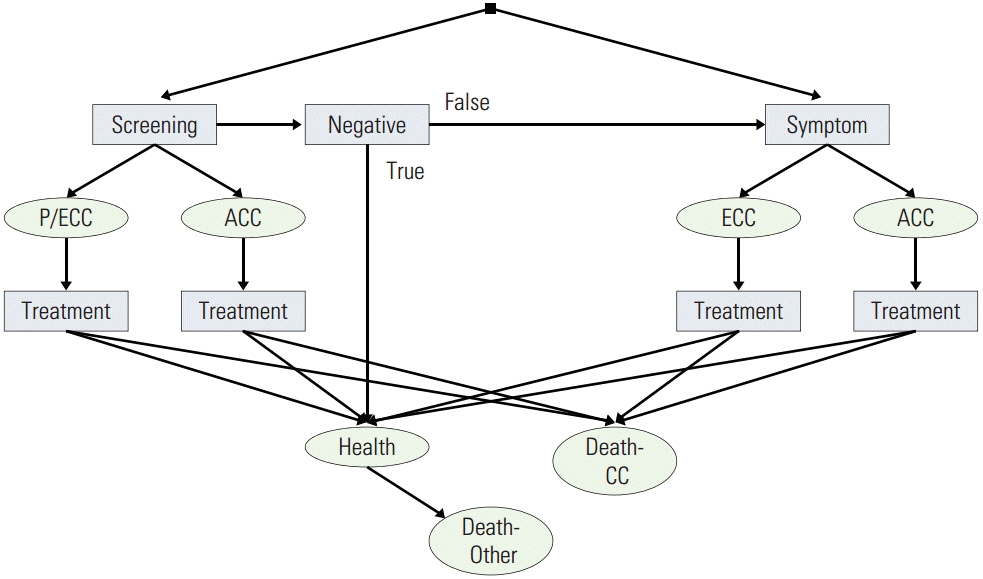

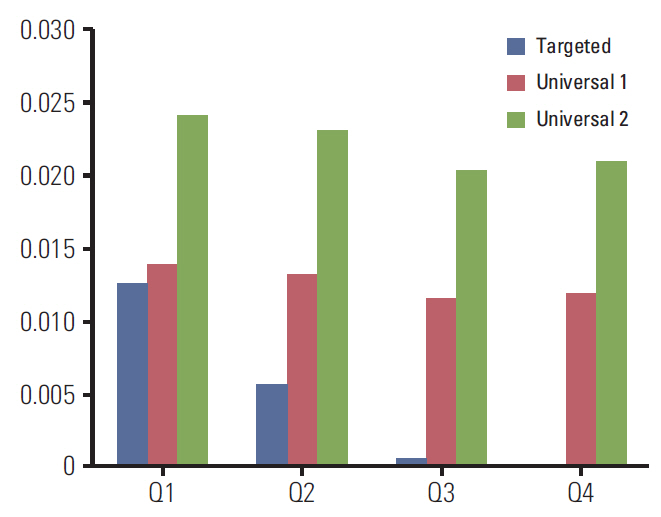

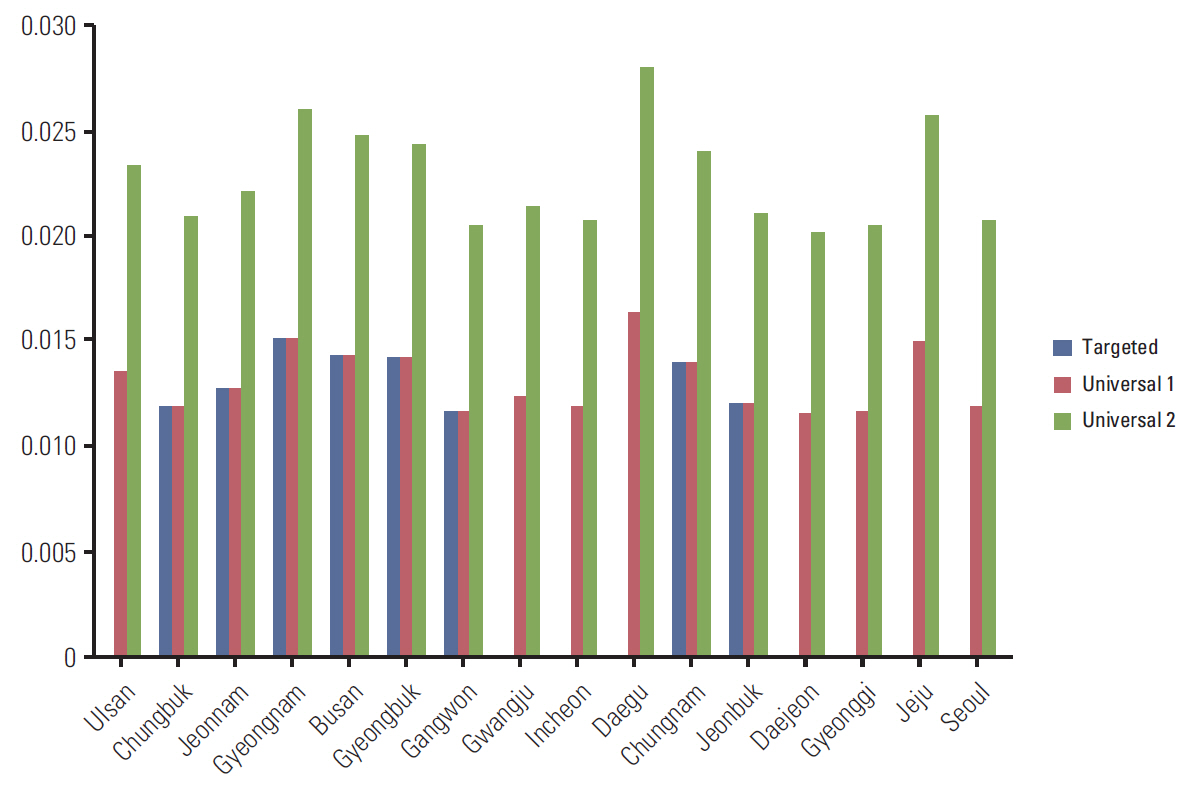

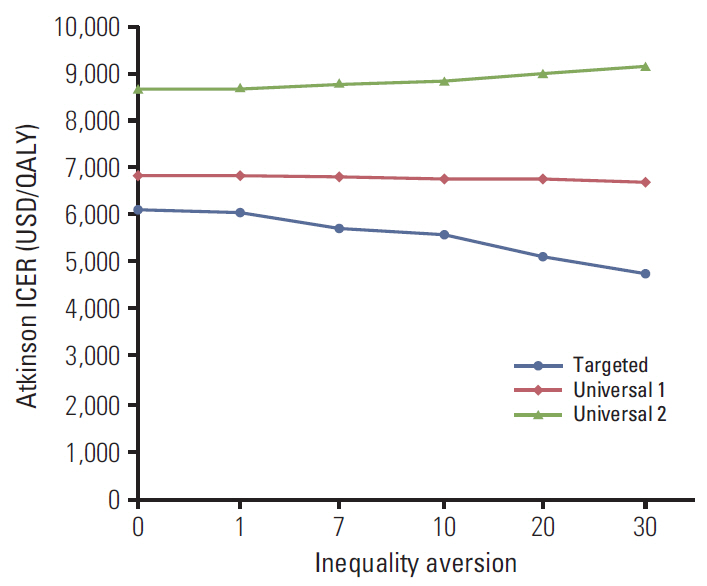

Markov cohort simulation was conducted with the cycle/duration of 1/40 year(s). Data came from the results of randomized trials and others. Participants were hypothetical cohorts aged 50 years as of year 2013 in 16 Korean provinces. The interventions until the age of 80 were annual organized fecal occult blood test (FOBT) (standard screening), annual FOBT with basic reminders for provinces with higher mortalities than the national average (targeted reminder) and annual FOBT with basic/enhanced reminders for all provinces (universal reminder 1 and 2). The comparison was non-screening, the outcome was quality-adjusted life years, and only medical costs for screening and treatment were considered from a societal perspective. The Atkinson incremental cost effectiveness ratio (Atkinson ICER), the incremental cost effectiveness ratio adjusted by the Atkinson Inequality Index, was used to evaluate the cost effectiveness of the four interventions with their impacts on regional health disparity being considered.

RESULTS

Health disparity was smallest (or greatest) in non-screening (or the standard screening). The targeted reminder had smaller health disparity, and smaller Atkinson ICER with respect to standard screening, than did the universal reminder 1 and 2.

CONCLUSION

The targeted reminder might be more cost effective than the universal reminders with their effects on health disparity being considered. This study helps to develop promotional effort for colorectal cancer screening with both the greatest cost effectiveness and the smallest health disparity.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Strategic Distributional Cost-Effectiveness Analysis for Improving National Cancer Screening Uptake in Cervical Cancer: A Focus on Regional Inequality in South Korea

Tae-Hoon Lee, Woorim Kim, Jaeyong Shin, Eun-Cheol Park, Sohee Park, Tae Hyun Kim

Cancer Res Treat. 2018;50(1):212-221. doi: 10.4143/crt.2016.525.

Reference

-

References

1. International Agency for Research on Cancer. GLOBOCAN 2012: estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012 [Internet]. Lyon: IARC;2015. [cited 2015 Jul 26]. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Default.aspx.2. American Cancer Society. Colorectal cancer facts and figures 2011-2013. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society;2011.3. Logan RF, Patnick J, Nickerson C, Coleman L, Rutter MD, von Wagner C. Outcomes of the Bowel Cancer Screening Programme (BCSP) in England after the first 1 million tests. Gut. 2012; 61:1439–46.

Article4. Korean National Cancer Center. Korea cancer facts and figures 2014. Goyang: Korean National Cancer Center;2014.5. Asaria M, Griffin S, Cookson R, Whyte S, Tappenden P. Distributional cost-effectiveness analysis of health care programmes: a methodological case study of the UK Bowel Cancer Screening Programme. Health Econ. 2015; 24:742–54.6. Korean Statistical Information Service [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2015. [cited 2015 Feb 28]. Available from: http://kosis.kr/.7. Park SM, Yun YH, Kwon S. Feasible economic strategies to improve screening compliance for colorectal cancer in Korea. World J Gastroenterol. 2005; 11:1587–93.

Article8. Markowitz AJ, Winawer SJ. Management of colorectal polyps. CA Cancer J Clin. 1997; 47:93–112.

Article9. Brenner H, Altenhofen L, Katalinic A, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Hoffmeister M. Sojourn time of preclinical colorectal cancer by sex and age: estimates from the German national screening colonoscopy database. Am J Epidemiol. 2011; 174:1140–6.

Article10. Djalalov S, Rabeneck L, Tomlinson G, Bremner KE, Hilsden R, Hoch JS. A review and meta-analysis of colorectal cancer utilities. Med Decis Making. 2014; 34:809–18.

Article11. Ladabaum U, Allen J, Wandell M, Ramsey S. Colorectal cancer screening with blood-based biomarkers: cost-effectiveness of methylated septin 9 DNA versus current strategies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013; 22:1567–76.

Article12. Shin A, Choi KS, Jun JK, Noh DK, Suh M, Jung KW, et al. Validity of fecal occult blood test in the national cancer screening program, Korea. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e79292.

Article13. Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Knudsen AB, Brenner H. Cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening. Epidemiol Rev. 2011; 33:88–100.

Article14. Whyte S, Walsh C, Chilcott J. Bayesian calibration of a natural history model with application to a population model for colorectal cancer. Med Decis Making. 2011; 31:625–41.

Article15. Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, Snover DC, Bradley GM, Schuman LM, et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study. N Engl J Med. 1993; 328:1365–71.16. Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, Lederle FA, Bond JH, Mandel JS, et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369:1106–14.

Article17. Shankaran V, McKoy JM, Dandade N, Nonzee N, Tigue CA, Bennett CL, et al. Costs and cost-effectiveness of a low-intensity patient-directed intervention to promote colorectal cancer screening. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25:5248–53.

Article18. Hewitson P, Ward AM, Heneghan C, Halloran SP, Mant D. Primary care endorsement letter and a patient leaflet to improve participation in colorectal cancer screening: results of a factorial randomised trial. Br J Cancer. 2011; 105:475–80.

Article19. Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare. Notification 2014-2: National medicial checkup guideline. Sejong: Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare;2014.20. World Bank. World development indicators [Internet]. Washington, DC: World Bank;2015. [cited 2015 Feb 28]. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators.21. Korea National Health Insurance Corporation. Korea national insurance statistical yearbook 2012. Wonju: Korea National Health Insurance Corporation;2013.22. Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011; 103:117–28.

Article23. Atkinson AB. On the measure of inequality. J Econ Theor. 1970; 2:244–63.24. Pirttila J, Uusitalo R. A ‘Leaky Bucket’ in the real world: estimating inequality aversion using survey data. Economica. 2010; 77:60–76.25. Lambert PJ, Millimet DL, Slottje D. Inequality aversion and the natural rate of subjective inequality. J Public Econ. 2003; 87:1061–90.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Cost Effectiveness of Interventions to Promote Screening for Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Trial

- Methodological Review of Cost Effectiveness Analysis of Cancer Screening

- Establishing Cancer Screening Recommendations for Major Cancers in Korea

- Cost-Utility Analysis for Colorectal Cancer Screening According to the Initiating Age of National Cancer Screening Program in Korea

- Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Colon Cancer Screening by Colonosopic Examination in Korea