J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2015 Jun;56(6):891-899. 10.3341/jkos.2015.56.6.891.

Intraocular Pressure Elevation after 0.7 mg Intravitreal Dexamethasone (Ozurdex(R)) Implantation: A One Year Follow-Up

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. wismile@schmc.ac.kr

- KMID: 2339154

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2015.56.6.891

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To investigate the percentage and time of intraocular pressure (IOP) elevation and the factors influencing IOP elevation and treatment.

METHODS

Thirty patients (33 eyes) who received intravitreal dexamethasone implantation from July 2012 to December 2013 and followed up more than 1 year were evaluated by measuring Goldmann IOP and confirming changes in IOP. The definition of IOP elevation was IOP above 20 mm Hg or IOP increase greater than 6 mm Hg.

RESULTS

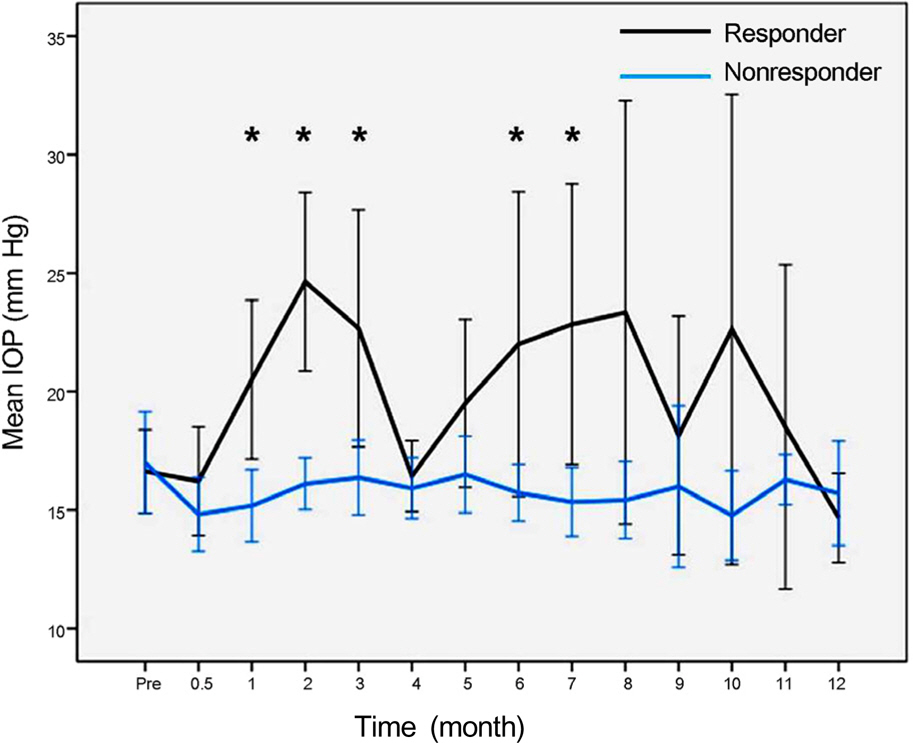

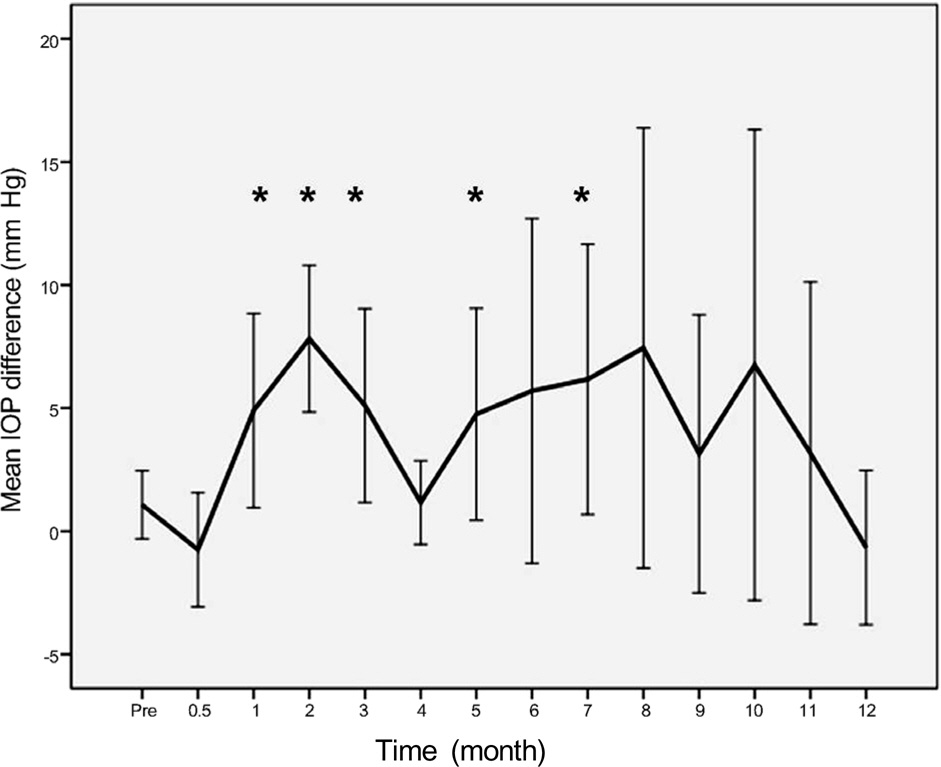

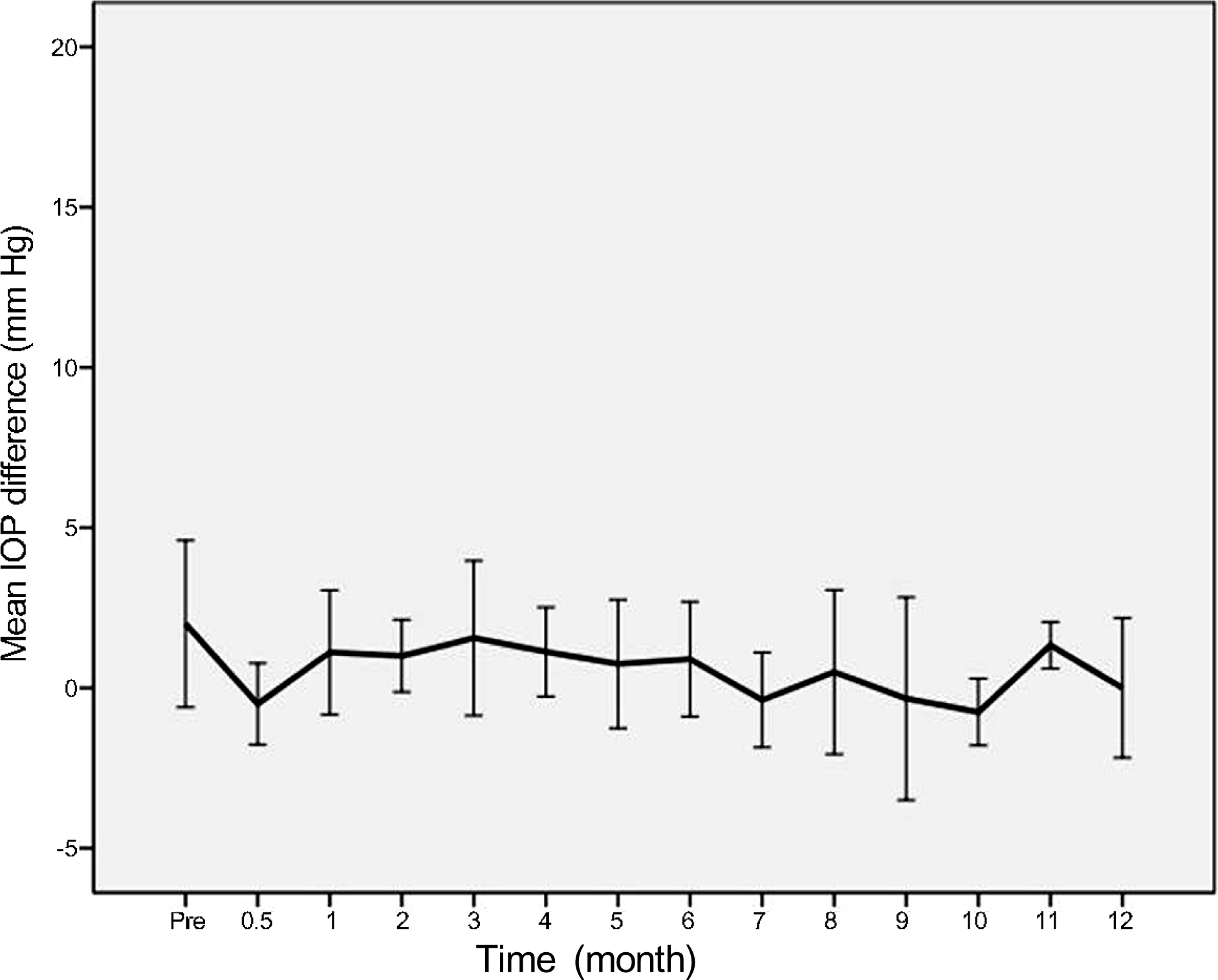

In 16 eyes (48.5%), IOP was elevated after intravitreal dexamethasone implantation. The first IOP elevation was mean 2.0 +/- 0.7 months. In 21 eyes which received intravitreal dexamethasone implantation more than twice, the mean intervals of implantation were 4.5 months. In steroid responders, IOP after dexamethasone implantation was significantly increased at 1, 2, 3, 6, and 7 months. IOP increase in the treated eye was significant at 1, 2, 3, 5, and 7 months after dexamethasone implantation.

CONCLUSIONS

After intravitreal dexamethasone implantation, IOP was highest at 2 months. Additionally, IOP was elevated in approximately half of the patients (48.5%). Although the intravitreal dexamethasone implantation is effective against various diseases which occur due to macular edema, thorough identification of suitable patients and frequent IOP control is necessary for long-term treatment.

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

One-year Outcome of Intravitreal Dexamethasone Implant for Diabetic Macular Edema Patients

No Hae Park, Hyun Duck Kwak, Chang Ki Yoon, Ji Eun Lee, Min Sagong, Sang Joon Lee, Joo Eun Lee, Kun Hyung Kim, Hyun Woong Kim

J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2019;60(2):135-143. doi: 10.3341/jkos.2019.60.2.135.

Reference

-

References

1. Campochiaro PA, Hafiz G, Shah SM, et al. Ranibizumab for macular edema due to retinal vein occlusions: implication of VEGF as a critical stimulator. Mol Ther. 2008; 16:791–9.

Article2. Chen KH, Wu CC, Roy S, et al. Increased interleukin-6 in aqueous humor of neovascular glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999; 40:2627–32.3. Owen LA, Hartnett ME. Soluble mediators of diabetic macular edema: the diagnostic role of aqueous VEGF and cytokine levels in diabetic macular edema. Curr Diab Rep. 2013; 13:476–80.

Article4. Rogers S, McIntosh RL, Cheung N, et al. The prevalence of retinal vein occlusion: pooled data from population studies from the United States, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Ophthalmology. 2010; 117:313–9.e1.

Article5. Mitchell P, Smith W, Chang A. Prevalence and associations of retinal vein occlusion in Australia. The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996; 114:1243–7.

Article6. Rehak J, Rehak M. Branch retinal vein occlusion: pathogenesis, visual prognosis, and treatment modalities. Curr Eye Res. 2008; 33:111–31.

Article7. Lowder C, Belfort R Jr, Lightman S, et al. Dexamethasone intravitreal implant for noninfectious intermediate or posterior uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011; 129:545–53.

Article8. Freeman G, Matos K, Pavesio CE. Cystoid macular oedema in uveitis: an unsolved problem. Eye (Lond). 2001; 15(Pt 1):12–7.

Article9. Hunter RS, Lobo AM. Dexamethasone intravitreal implant for the treatment of noninfectious uveitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011; 5:1613–21.10. Yeh PC, Ramanathan S. Latanoprost and clinically significant cystoid macular edema after uneventful phacoemulsification with intraocular lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002; 28:1814–8.

Article11. Arcieri ES, Santana A, Rocha FN, et al. Blood-aqueous barrier changes after the use of prostaglandin analogues in patients with pseudophakia and aphakia: a 6-month randomized trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005; 123:186–92.12. Boyer DS, Yoon YH, Belfort R Jr, et al. Three-year, randomized, sham-controlled trial of dexamethasone intravitreal implant in patients with diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2014; 121:1904–14.

Article13. Haller JA, Bandello F, Belfort R Jr, et al. Dexamethasone intravitreal implant in patients with macular edema related to branch or central retinal vein occlusion twelve-month study results. Ophthalmology. 2011; 118:2453–60.14. Leopold IH. Update on antibiotics in ocular infections. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985; 100:134–40.

Article15. Zalewski D, Raczyńska D, Raczyńska K. Five-month observation of persistent diabetic macular edema after intravitreal injection of Ozurdex implant. Mediators Inflamm. 2014; 2014:364143.

Article16. Guigou S, Hajjar C, Parrat E, et al. Multicenter Ozurdex(R) assessment for diabetic macular edema: MOZART study. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2014; 37:480–5.17. Furino C, Boscia F, Recchimurzo N, et al. Intravitreal dexamethasone implant for macular edema following uncomplicated phacoemulsification. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2014; 24:387–91.

Article18. Gallego-Pinazo R, Marín-Lambíes C, Marín-Olmos F, et al. Intravitreal dexamethasone as an enhancer for the anti-VEGF treatment in neovascular ARMD: recovering an old ally. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2010; 85:79–80.

Article19. Latronico ME, Rigante D, Caso F, et al. Bilateral dexamethasone intravitreal implant in a young patient with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease and refractory uveitis. Clin Rheumatol. 2014 Apr 25; [Epub].

Article20. Kapoor KG, Wagner MG, Wagner AL. The sustained-release dexamethasone implant: expanding indications in vitreoretinal disease. Semin Ophthalmol. 2014 Mar 21; [Epub ahead of print].

Article21. Saatci AO, Doruk HC, Yaman A. Intravitreal dexamethasone implant (ozurdex) in coats' disease. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2013; 4:122–8.

Article22. Haller JA, Bandello F, Belfort R Jr, et al. Randomized, sham-con-trolled trial of dexamethasone intravitreal implant in patients with macular edema due to retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 2010; 117:1134–46.e3.

Article23. Becker B. Intraocular pressure response to topical corticosteroids. Invest Ophthalmol. 1965; 4:198–205.24. Armaly MF. Statistical attributes of the steroid hypertensive response in the clinically normal eye. I. The demonstration of three levels of response. Invest Ophthalmol. 1965; 4:187–97.25. Meyer LM, Schönfeld CL. Secondary glaucoma after intravitreal dexamethasone 0.7 mg implant in patients with retinal vein occlusion: a one-year follow-up. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2013; 29:560–5.26. Kubota T, Okabe H, Hisatomi T, et al. Ultrastructure of the trabecular meshwork in secondary glaucoma eyes after intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide. J Glaucoma. 2006; 15:117–9.

Article27. Jones R 3rd, Rhee DJ. Corticosteroid-induced ocular hypertension and glaucoma: a brief review and update of the literature. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006; 17:163–7.28. Wordinger RJ, Clark AF. Effects of glucocorticoids on the trabecular meshwork: towards a better understanding of glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999; 18:629–67.

Article29. Kersey JP, Broadway DC. Corticosteroid-induced glaucoma: a review of the literature. Eye (Lond). 2006; 20:407–16.

Article30. Kiddee W, Trope GE, Sheng L, et al. Intraocular pressure monitoring post intravitreal steroids: a systematic review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013; 58:291–310.

Article31. Kang HK, Chin HS. Complications after intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide injection: incidence and risk factors. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2012; 53:76–86.

Article32. Rubin B, Taglienti A, Rothman RF, et al. The effect of selective laser trabeculoplasty on intraocular pressure in patients with intravitreal steroid-induced elevated intraocular pressure. J Glaucoma. 2008; 17:287–92.

Article33. Lee JH, Seong MC, Cho HY, Lee YJ. The effectiveness of selective laser trabeculoplasty in steroid-induced ocular hypertension. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2011; 52:876–80.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Repeated Intravitreal Dexamethasone Implantation for Treatment of Macular Edema after Scleral Fixation of Intraocular Lens

- Risk Factors and Incidence of Elevated Intraocular Pressure after Dexamethasone Intravitreal Implant

- Intraocular Pressure Changes in Patients with Retinal Vein Occlusion Treated with Intravitreal Dexamethasone Implant Insertion

- Suspected Bacterial Endophthalmitis Following Sustained-release Dexamethasone Intravitreal Implant: A Case Report

- Clinical Manifestations of Intraocular Pressure Elevation after Intravitreal Injection of Triamcinolone Acetonide