Tuberc Respir Dis.

2015 Oct;78(4):401-407. 10.4046/trd.2015.78.4.401.

Different Responses to Clarithromycin in Patients with Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Allergy and Respiratory Medicine, Soonchunhyang University Hospital, Seoul, Korea. uhs@schmc.ac.kr

- 2Department of Thoracic Surgery, Soonchunhyang University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Pathology, Soonchunhyang University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2320715

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4046/trd.2015.78.4.401

Abstract

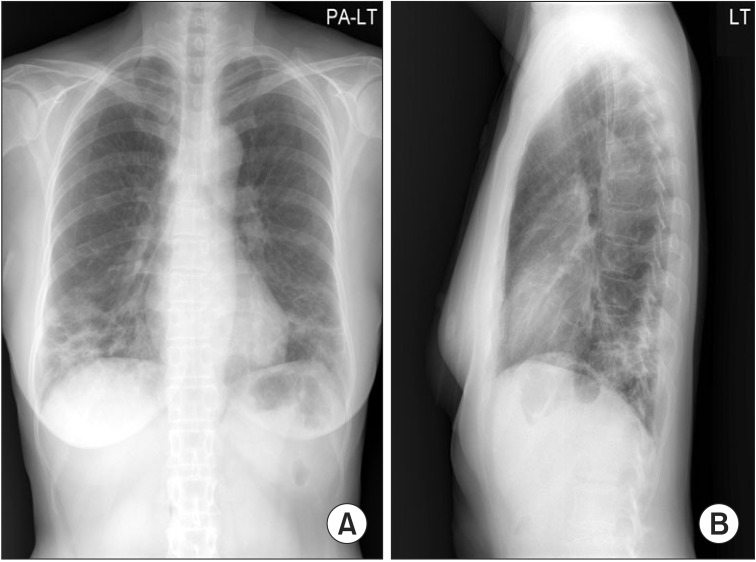

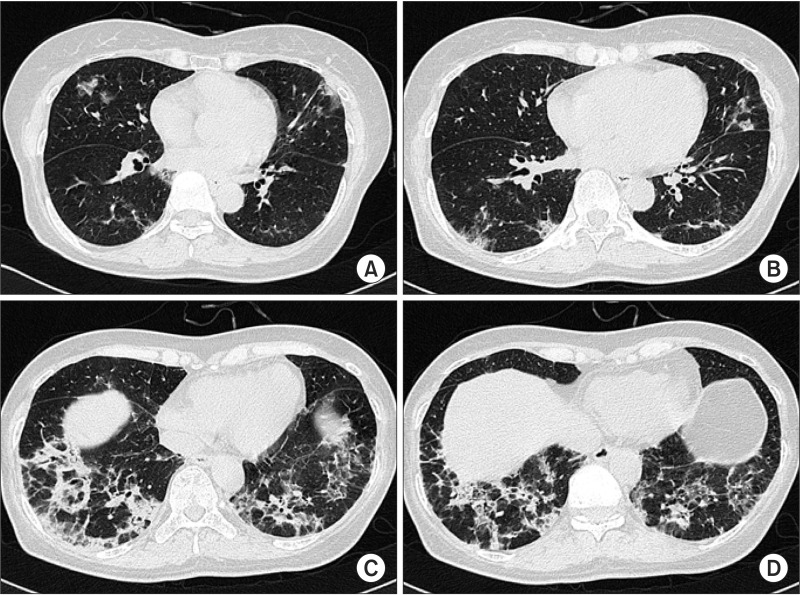

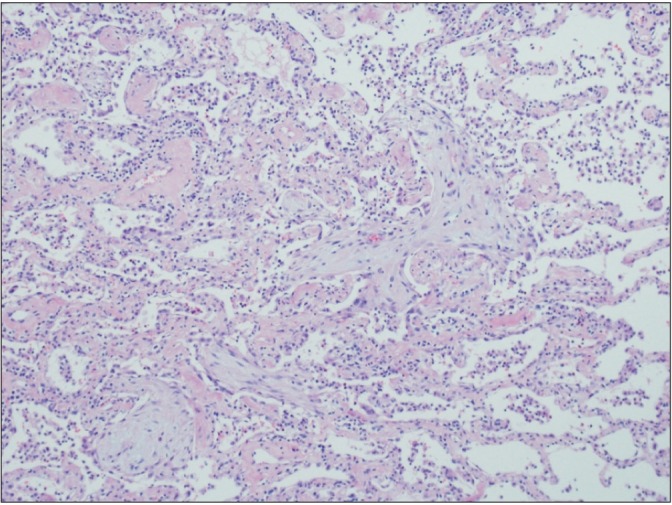

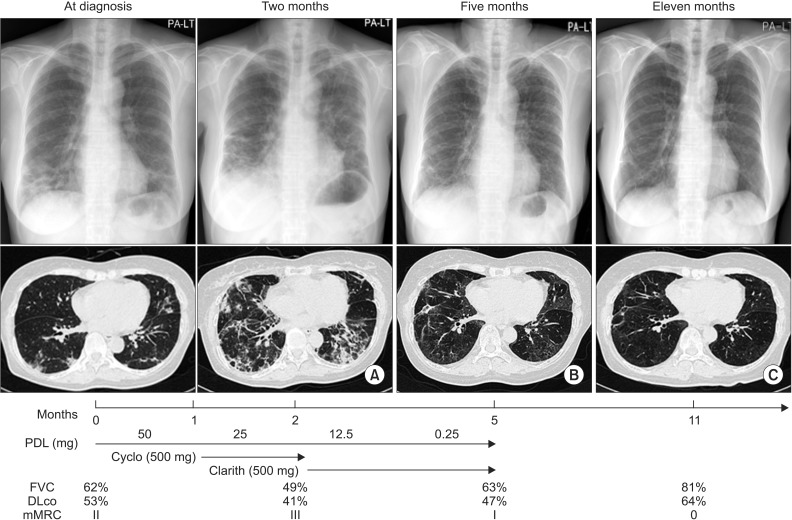

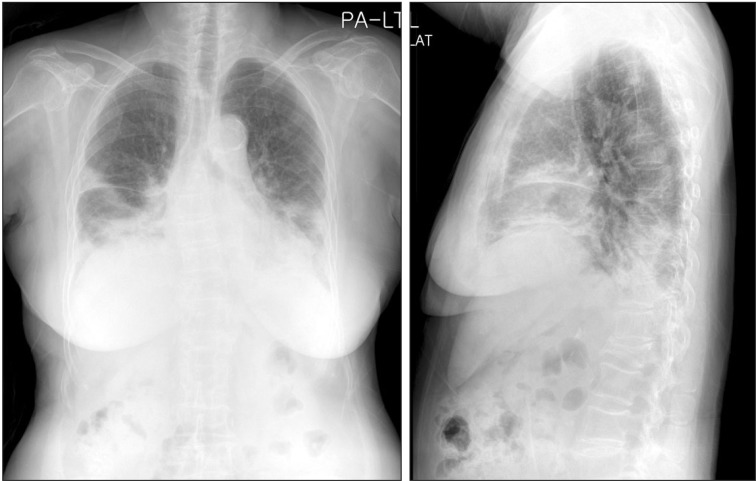

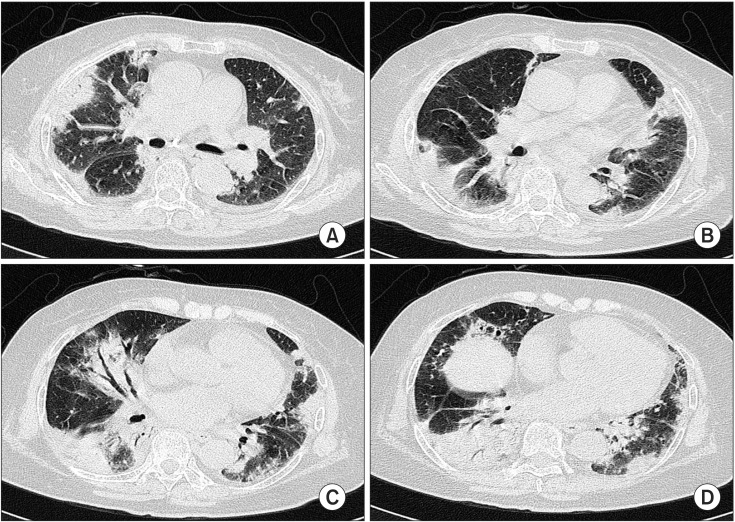

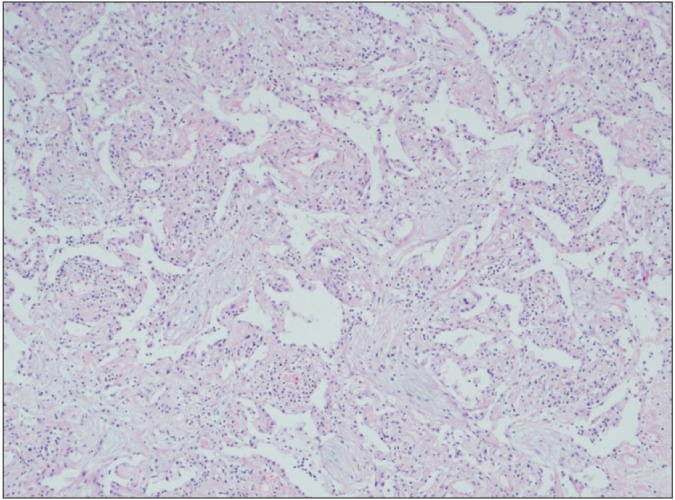

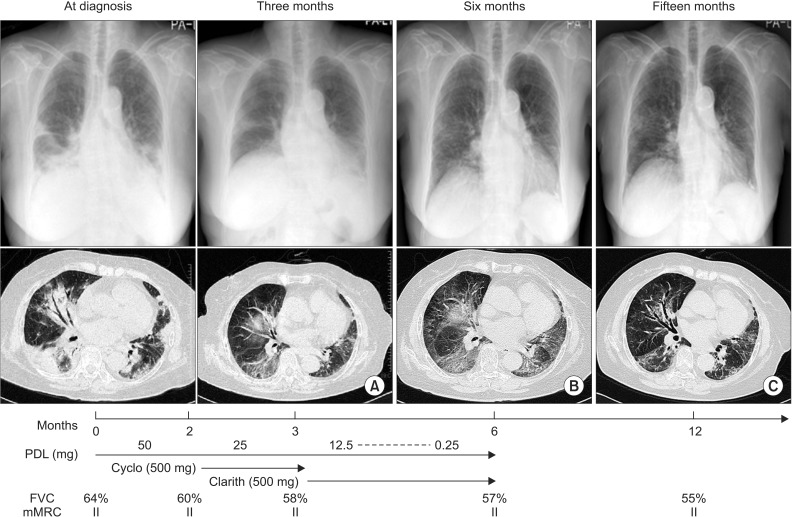

- Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) is an idiopathic interstitial pneumonia characterized by a subacute course and favorable prognosis with corticosteroids. However, some patients show resistance to steroids. Macrolides have been used with success in those patients showing resistance to steroids. A few reports showed treatment failure with macrolides in patients with COP who were resistant to steroids. In this report, we described two cases of COP who showed different responses to clarithromycin. One recovered completely, but the other gradually showed lung fibrosis with clarithromycin.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Drakopanagiotakis F, Paschalaki K, Abu-Hijleh M, Aswad B, Karagianidis N, Kastanakis E, et al. Cryptogenic and secondary organizing pneumonia: clinical presentation, radiographic findings, treatment response, and prognosis. Chest. 2011; 139:893–900. PMID: 20724743.2. Yousem SA, Lohr RH, Colby TV. Idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia/cryptogenic organizing pneumonia with unfavorable outcome: pathologic predictors. Mod Pathol. 1997; 10:864–871. PMID: 9310948.3. Chang WJ, Lee EJ, Lee SY, In KH, Kim CH, Kim HK, et al. Successful salvage treatment of steroid-refractory bronchiolar COP with low-dose macrolides. Pathol Int. 2012; 62:144–148. PMID: 22243785.

Article4. Ichikawa Y, Ninomiya H, Katsuki M, Hotta M, Tanaka M, Oizumi K. Low-dose/long-term erythromycin for treatment of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP). Kurume Med J. 1993; 40:65–67. PMID: 8231065.

Article5. Lee J, Cha SI, Park TI, Park JY, Jung TH, Kim CH. Adjunctive effects of cyclosporine and macrolide in rapidly progressive cryptogenic organizing pneumonia with no prompt response to steroid. Intern Med. 2011; 50:475–479. PMID: 21372463.

Article6. Adibelli Z, Dilek M, Kocak B, Tulek N, Uzun O, Akpolat T. An unusual presentation of sirolimus associated cough in a renal transplant recipient. Transplant Proc. 2007; 39:3463–3464. PMID: 18089408.

Article7. Stover DE, Mangino D. Macrolides: a treatment alternative for bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia? Chest. 2005; 128:3611–3617. PMID: 16304320.8. Radzikowska E, Wiatr E, Gawryluk D, Langfort R, Bestry I, Chabowski M, et al. Organizing pneumonia: clarithromycin treatment. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2008; 76:334–339. PMID: 19003763.9. Nizami IY, Kissner DG, Visscher DW, Dubaybo BA. Idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia: an acute and life-threatening syndrome. Chest. 1995; 108:271–277. PMID: 7606970.10. Ichikawa Y, Ninomiya H, Koga H, Tanaka M, Kinoshita M, Tokunaga N, et al. Erythromycin reduces neutrophils and neutrophil-derived elastolytic-like activity in the lower respiratory tract of bronchiolitis patients. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992; 146:196–203. PMID: 1626803.

Article11. Sakito O, Kadota J, Kohno S, Abe K, Shirai R, Hara K. Interleukin 1 beta, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin 8 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with diffuse panbronchiolitis: a potential mechanism of macrolide therapy. Respiration. 1996; 63:42–48. PMID: 8833992.12. Nelson S, Summer WR, Terry PB, Warr GA, Jakab GJ. Erythromycin-induced suppression of pulmonary antibacterial defenses: a potential mechanism of superinfection in the lung. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987; 136:1207–1212. PMID: 3314615.

Article13. Aoki Y, Kao PN. Erythromycin inhibits transcriptional activation of NF-kappaB, but not NFAT, through calcineurin-independent signaling in T cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999; 43:2678–2684. PMID: 10543746.14. Cohen AJ, King TE Jr, Downey GP. Rapidly progressive bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994; 149:1670–1675. PMID: 8004328.

Article15. Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011; 183:788–824. PMID: 21471066.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Rheumatoid Arthritis accompanied by Organizing Pneumonia Successfully Treated with Prednisolone, Clarithromycin and Tacrolimus

- A Case of Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia after Transarterial Chemoembolization for the Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

- Korean Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Interstitial Lung Diseases: Part 4. Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia

- Development of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia during standard treatment of hepatitis C with Peg-IFNα2b

- A Case of Organizing Pneumonia Associated with FOLFIRI Chemotherapy