Tuberc Respir Dis.

2012 Jan;72(1):30-36.

Role of Microbiologic Culture Results of Specimens Prior to Onset of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia in the Patients Admitted to Intensive Care Unit

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Konyang University College of Medicine, Daejon, Korea. sjoongkwon@hanmail.net

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) in intensive care unit (ICU) have a high mortality rate. The routine surveillance cultures obtained previously or an ATS guideline for hospital-acquired pneumonia was used in selecting initial antimicrobials. The object of this study was to compare the respiratory samples before VAP and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) culture.

METHODS

54 patients underwent fiberoptic bronchoscopy to obtain BAL samples. We reviewed microbiologic specimen results of prior respiratory specimens (pre-VAP) and BAL.

RESULTS

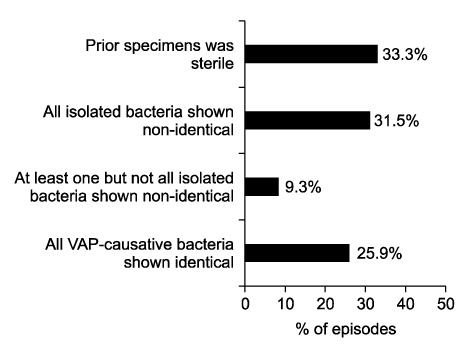

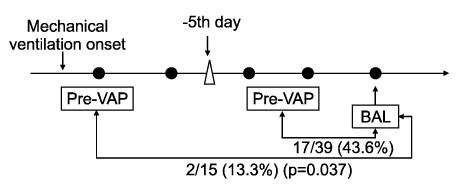

Among 51 patients with 54 VAP episodes, 52 microorganisms of pre-VAP and 56 BAL samples were isolated. Pre-VAP included 21.2% of MRSA, and 32.6% of multidrug resistant-Acinetobacter baumannii (MDR-AB). BAL samples comprised 25.0% of MRSA, 26.7% of MDR-AB, 14.3% of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and 3.6% of Klebsiella pneumonia in order. In pre-VAP samples compared to BAL samples, only 35.2% were identical. In BAL samples compared to pre-VAP samples obtained in 5 days before the onset of VAP, only 43.6% were identical. However, among BAL samples compared to pre-VAP samples obtained after more than 5 days, 13.3% were identical (p=0.037).

CONCLUSION

Based on these data, pre-VAP samples obtained prior to 5 day onset of VAP may help to predict the causative microorganisms and to select appropriate initial antimicrobials.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) system report, data summary from January 1992-April 2000, issued June 2000. Am J Infect Control. 2000. 28:429–448.2. Richards MJ, Edwards JR, Culver DH, Gaynes RP. Nosocomial infections in medical intensive care units in the United States. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Crit Care Med. 1999. 27:887–892.3. Fagon JY, Chastre J, Vuagnat A, Trouillet JL, Novara A, Gibert C. Nosocomial pneumonia and mortality among patients in intensive care units. JAMA. 1996. 275:866–869.4. Papazian L, Bregeon F, Thirion X, Gregoire R, Saux P, Denis JP, et al. Effect of ventilator-associated pneumonia on mortality and morbidity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996. 154:91–97.5. Rello J, Quintana E, Ausina V, Castella J, Luquin M, Net A, et al. Incidence, etiology, and outcome of nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients. Chest. 1991. 100:439–444.6. Iregui M, Ward S, Sherman G, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. Clinical importance of delays in the initiation of appropriate antibiotic treatment for ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2002. 122:262–268.7. American Thoracic Society. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005. 171:388–416.8. Bouza E, Pérez A, Muñoz P, Jesús Pérez M, Rincón C, Sánchez C, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia after heart surgery: a prospective analysis and the value of surveillance. Crit Care Med. 2003. 31:1964–1970.9. Joseph NM, Sistla S, Dutta TK, Badhe AS, Parija SC. Ventilator-associated pneumonia: role of colonizers and value of routine endotracheal aspirate cultures. Int J Infect Dis. 2010. 14:e723–e729.10. Jung B, Sebbane M, Chanques G, Courouble P, Verzilli D, Perrigault PF, et al. Previous endotracheal aspirate allows guiding the initial treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2009. 35:101–107.11. Sanders KM, Adhikari NK, Friedrich JO, Day A, Jiang X, Heyland D, et al. Previous cultures are not clinically useful for guiding empiric antibiotics in suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia: secondary analysis from a randomized trial. J Crit Care. 2008. 23:58–63.12. Michel F, Franceschini B, Berger P, Arnal JM, Gainnier M, Sainty JM, et al. Early antibiotic treatment for BAL-confirmed ventilator-associated pneumonia: a role for routine endotracheal aspirate cultures. Chest. 2005. 127:589–597.13. Hayon J, Figliolini C, Combes A, Trouillet JL, Kassis N, Dombret MC, et al. Role of serial routine microbiologic culture results in the initial management of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002. 165:41–46.14. Lucet JC, Decré D, Fichelle A, Joly-Guillou ML, Pernet M, Deblangy C, et al. Control of a prolonged outbreak of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing enterobacteriaceae in a university hospital. Clin Infect Dis. 1999. 29:1411–1418.15. Meduri GU, Chastre J. The standardization of bronchoscopic techniques for ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 1992. 102:5 Suppl 1. 557S–564S.16. Delclaux C, Roupie E, Blot F, Brochard L, Lemaire F, Brun-Buisson C. Lower respiratory tract colonization and infection during severe acute respiratory distress syndrome: incidence and diagnosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997. 156:1092–1098.17. Sirvent JM, Torres A, Vidaur L, Armengol J, de Batlle J, Bonet A. Tracheal colonisation within 24 h of intubation in patients with head trauma: risk factor for developing early-onset ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2000. 26:1369–1372.18. Hospital-acquired pneumonia in adults: diagnosis, assessment of severity, initial antimicrobial therapy, and preventive strategies. A consensus statement, American Thoracic Society, November 1995. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996. 153:1711–1725.19. Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Griffith L, Keenan SP, Brun-Buisson C. The Canadian Critical Trials Group. The attributable morbidity and mortality of ventilator-associated pneumonia in the critically ill patient. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999. 159:1249–1256.20. Garnacho-Montero J, Ortiz-Leyba C, Fernández-Hinojosa E, Aldabó-Pallás T, Cayuela A, Marquez-Vácaro JA, et al. Acinetobacter baumannii ventilator-associated pneumonia: epidemiological and clinical findings. Intensive Care Med. 2005. 31:649–655.21. Rahal JJ, Urban C, Horn D, Freeman K, Segal-Maurer S, Maurer J, et al. Class restriction of cephalosporin use to control total cephalosporin resistance in nosocomial Klebsiella. JAMA. 1998. 280:1233–1237.22. Trouillet JL, Chastre J, Vuagnat A, Joly-Guillou ML, Combaux D, Dombret MC, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by potentially drug-resistant bacteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998. 157:531–539.23. Kollef MH, Fraser VJ. Antibiotic resistance in the intensive care unit. Ann Intern Med. 2001. 134:298–314.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Impact of the Ventilator-associated Pneumonia Bundle in a Medical Intensive Care Unit

- Prevention and Management of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

- Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit : Clinical Manifestations, Ddiagnostic Availability of Endotracheal Tip Culture

- Incidence of Colonization, Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia as Related to the Type of Endotracheal Suction System in Mechanically Ventilated Patients

- Clinical Features and Outcomes of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Patients