Tuberc Respir Dis.

2010 Dec;69(6):411-417.

Asthma Year in Review

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea. sanghakim@yonsei.ac.kr

Abstract

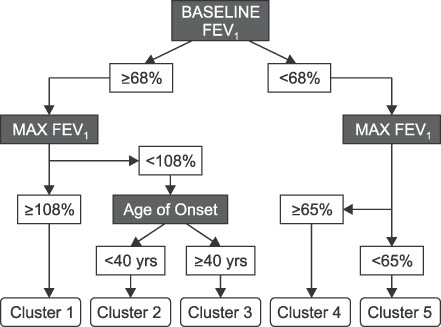

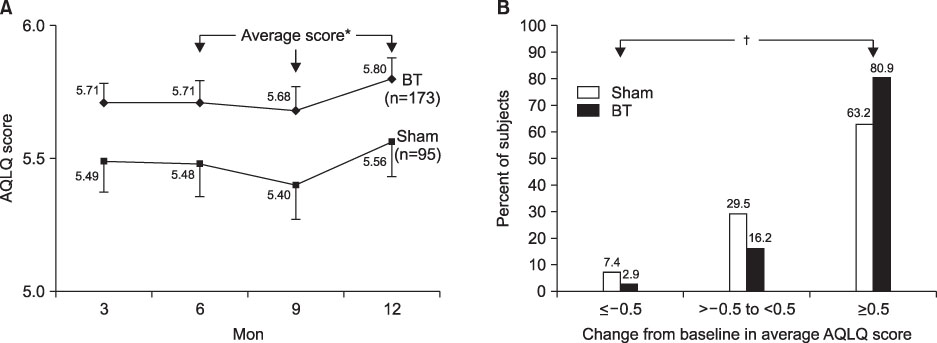

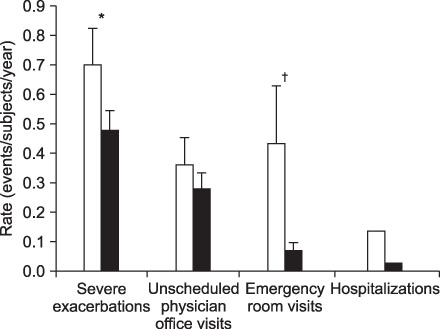

- This review highlights articles pertaining to the following 5 topics: the relationship between asthma, allergic and non-allergic rhinitis; the novel asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis; the diagnostic properties of inhaled dry-powder mannitol for the diagnosis of asthma; the value of mepolizumab therapy in exacerbations of refractory eosinophilic asthma; the role of bronchial thermoplasty in the treatment of severe asthma.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Shaaban R, Zureik M, Soussan D, Neukirch C, Heinrich J, Sunyer J, et al. Rhinitis and onset of asthma: a longitudinal population-based study. Lancet. 2008. 372:1049–1057.2. Bousquet J, Van Cauwenberge P, Khaltaev N. Aria Workshop Group. World Health Organization. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001. 108:S147–S334.3. Guerra S, Sherrill DL, Martinez FD, Barbee RA. Rhinitis as an independent risk factor for adult-onset asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002. 109:419–425.4. Plaschke PP, Janson C, Norrman E, Björnsson E, Ellbjär S, Järvholm B. Onset and remission of allergic rhinitis and asthma and the relationship with atopic sensitization and smoking. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000. 162:920–924.5. Leynaert B, Neukirch C, Kony S, Guénégou A, Bousquet J, Aubier M, et al. Association between asthma and rhinitis according to atopic sensitization in a population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004. 113:86–93.6. Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, Teague WG, Li H, Li X, et al. Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010. 181:315–323.7. Moore WC, Bleecker ER, Curran-Everett D, Erzurum SC, Ameredes BT, Bacharier L, et al. Characterization of the severe asthma phenotype by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Severe Asthma Research Program. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007. 119:405–413.8. Sverrild A, Porsbjerg C, Thomsen SF, Backer V. Diagnostic properties of inhaled mannitol in the diagnosis of asthma: a population study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009. 124:928–932.9. Brusasco V, Crimi E. Methacholine provocation test for diagnosis of allergic respiratory diseases. Allergy. 2001. 56:1114–1120.10. de Meer G, Marks GB, Postma DS. Direct or indirect stimuli for bronchial challenge testing: what is the relevance for asthma epidemiology? Clin Exp Allergy. 2004. 34:9–16.11. Anderson SD. Provocative challenges to help diagnose and monitor asthma: exercise, methacholine, adenosine, and mannitol. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2008. 14:39–45.12. Porsbjerg C, Brannan JD, Anderson SD, Backer V. Relationship between airway responsiveness to mannitol and to methacholine and markers of airway inflammation, peak flow variability and quality of life in asthma patients. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008. 38:43–50.13. Haldar P, Brightling CE, Hargadon B, Gupta S, Monteiro W, Sousa A, et al. Mepolizumab and exacerbations of refractory eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2009. 360:973–984.14. Jatakanon A, Lim S, Barnes PJ. Changes in sputum eosinophils predict loss of asthma control. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000. 161:64–72.15. Deykin A, Lazarus SC, Fahy JV, Wechsler ME, Boushey HA, Chinchilli VM, et al. Sputum eosinophil counts predict asthma control after discontinuation of inhaled corticosteroids. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005. 115:720–727.16. Green RH, Brightling CE, McKenna S, Hargadon B, Parker D, Bradding P, et al. Asthma exacerbations and sputum eosinophil counts: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002. 360:1715–1721.17. Jayaram L, Pizzichini MM, Cook RJ, Boulet LP, Lemière C, Pizzichini E, et al. Determining asthma treatment by monitoring sputum cell counts: effect on exacerbations. Eur Respir J. 2006. 27:483–494.18. Nair P, Pizzichini MM, Kjarsgaard M, Inman MD, Efthimiadis A, Pizzichini E, et al. Mepolizumab for prednisone-dependent asthma with sputum eosinophilia. N Engl J Med. 2009. 360:985–993.19. Castro M, Rubin AS, Laviolette M, Fiterman J, De Andrade Lima M, Shah PL, et al. Effectiveness and safety of bronchial thermoplasty in the treatment of severe asthma: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010. 181:116–124.20. Cox PG, Miller J, Mitzner W, Leff AR. Radiofrequency ablation of airway smooth muscle for sustained treatment of asthma: preliminary investigations. Eur Respir J. 2004. 24:659–663.21. Danek CJ, Lombard CM, Dungworth DL, Cox PG, Miller JD, Biggs MJ, et al. Reduction in airway hyperresponsiveness to methacholine by the application of RF energy in dogs. J Appl Physiol. 2004. 97:1946–1953.22. Pavord ID, Cox G, Thomson NC, Rubin AS, Corris PA, Niven RM, et al. Safety and efficacy of bronchial thermoplasty in symptomatic, severe asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007. 176:1185–1191.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Treatment of Severe Asthma

- Clinical Year in Review of Asthma for Pulmonary Physicians : The Epidemiologic Hypothesis for the Relationship between Asthma and Infectious Disease

- The association between smoking and asthma

- Comparison and review of international guidelines for treating asthma in children

- Atopy is an important determinant to the development of asthma