Tuberc Respir Dis.

2008 Dec;65(6):512-516.

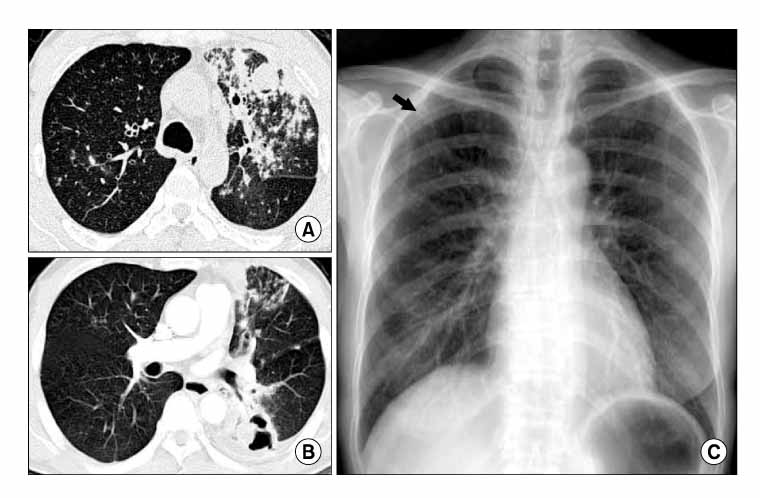

Use of Molecular Identification Analysis in a Case of Intra-familial Transmission of Tuberculosis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Respiratory and Allergy Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Soonchunhyang University, Seoul, Korea. kyklung@hosp.sch.ac.kr

- 2Korean Institute of Tuberculosis, Korean National Tuberculosis Association, Seoul, Korea.

Abstract

- No abstract available.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. American Thoracic Society. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infectious Diseases Society of America. American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America: controlling tuberculosis in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005. 172:1169–1227.2. Rose CE Jr, Zerbe GO, Lantz SO, Bailey WC. Establishing priority during investigation of tuberculosis contacts. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979. 119:603–609.3. Barnes PF, Cave MD. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2003. 349:1149–1156.4. Small PM, Hopewell PC, Singh SP, Paz A, Parsonnet J, Ruston DC, et al. The epidemiology of tuberculosis in San Francisco: a population-based study using conventional and molecular methods. N Engl J Med. 1994. 330:1703–1709.5. McNabb SJ, Kammerer JS, Hickey AC, Braden CR, Shang N, Rosenblum LS, et al. Added epidemiologic value to tuberculosis prevention and control of the investigation of clustered genotypes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. Am J Epidemiol. 2004. 160:589–597.6. Dahle UR, Nordtvedt S, Winje BA, Mannsaaker T, Heldal E, Sandven P, et al. Tuberculosis in contacts need not indicate disease transmission. Thorax. 2005. 60:136–137.7. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning, financing. WHO Report 2004. 2004. Geneva: World Health Organization.8. Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Korean Institute of Tuberculosis. Annual report on the notified tuberculosis patients in Korea. 2005. Seoul: Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Korean Institute of Tuberculosis.9. Kamat SR, Dawson JJ, Devadatta S, Fox W, Janardhanam B, Radhakrishna S, et al. A controlled study of the influence of segregation of tuberculous patients for one year on the attack rate of tuberculosis in a 5-year period in close family contacts in South India. Bull World Health Organ. 1966. 34:517–532.10. Gunnels JJ, Bates JH, Swindoll H. Infectivity of sputum-positive tuberculous patients on chemotherapy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1974. 109:323–330.11. Grzybowski S, Barnett GD, Styblo K. Contacts of cases of active pulmonary tuberculosis. Bull Int Union Tuberc. 1975. 50:90–106.12. Bailey WC, Gerald LB, Kimerling ME, Redden D, Brook N, Bruce F, et al. Predictive model to identify positive tuberculosis skin test results during contact investigations. JAMA. 2002. 287:996–1002.13. Leff A, Geppert EF. Public health and preventive aspects of pulmonary tuberculosis: infectiousness, epidemiology, risk factors, classification, and preventive therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1979. 139:1405–1410.14. Diagnostic Standards and Classification of Tuberculosis in Adults and Children. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. This statement was endorsed by the Council of the Infectious Disease Society of America, September 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000. 161:1376–1395.15. Jick SS, Lieberman ES, Rahman MU, Choi HK. Glucocorticoid use, other associated factors, and the risk of tuberculosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006. 55:19–26.16. van Embden JD, Cave MD, Crawford JT, Dale JW, Eisenach KD, Gicquel B, et al. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J Clin Microbiol. 1993. 31:406–409.17. Pai M, Zwerling A, Menzies D. Systematic review: T-cell-based assays for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: an update. Ann Intern Med. 2008. 149:177–184.18. Verver S, Warren RM, Munch Z, Richardson M, van der Spuy GD, Borgdorff MW, et al. Proportion of tuberculosis transmission that takes place in households in a high-incidence area. Lancet. 2004. 363:212–214.19. Menzies D, Pai M, Comstock G. Meta-analysis: new tests for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: areas of uncertainty and recommendations for research. Ann Intern Med. 2007. 146:340–354.20. Geng E, Kreiswirth B, Driver C, Li J, Burzynski J, DellaLatta P, et al. Changes in the transmission of tuberculosis in New York City from 1990 to 1999. N Engl J Med. 2002. 346:1453–1458.21. Park YK, Bai GH, Kim SJ. Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated from countries in the western pacific region. J Clin Microbiol. 2000. 38:191–197.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Familial Infestation of Paragonimus Westermani Diagnosed by ELISA -Report of two families-

- Laboratory Experience in Phenotypic and Molecular Identification of Blastomyces dermatitidis First Isolated in Korea

- Identification of Fastidious Mycobacteria other than M. tuberculosis ( MOTT ) by Comparative Sequence Analysis of rpoB and 16S rDNA

- Pulmonary Tuberculosis Diagnosis: Where We Are?

- New Diagnostic Methods for Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection