Pediatr Infect Vaccine.

2015 Dec;22(3):172-177. 10.14776/piv.2015.22.3.172.

Evaluation of Timeliness of Palivizumab Immunoprophylaxis Based on the Epidemic Period of Respiratory Syncytial Virus: 22 Year Experience in a Single Center

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Seoul National University Children's Hospital, Seoul, Korea. eunchoi@snu.ac.kr

- KMID: 2315682

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.14776/piv.2015.22.3.172

Abstract

- PURPOSE

This study aimed to analyze the epidemic period of RSV infection and evaluate the appropriate time of palivizumab immunoprophylaxis.

METHODS

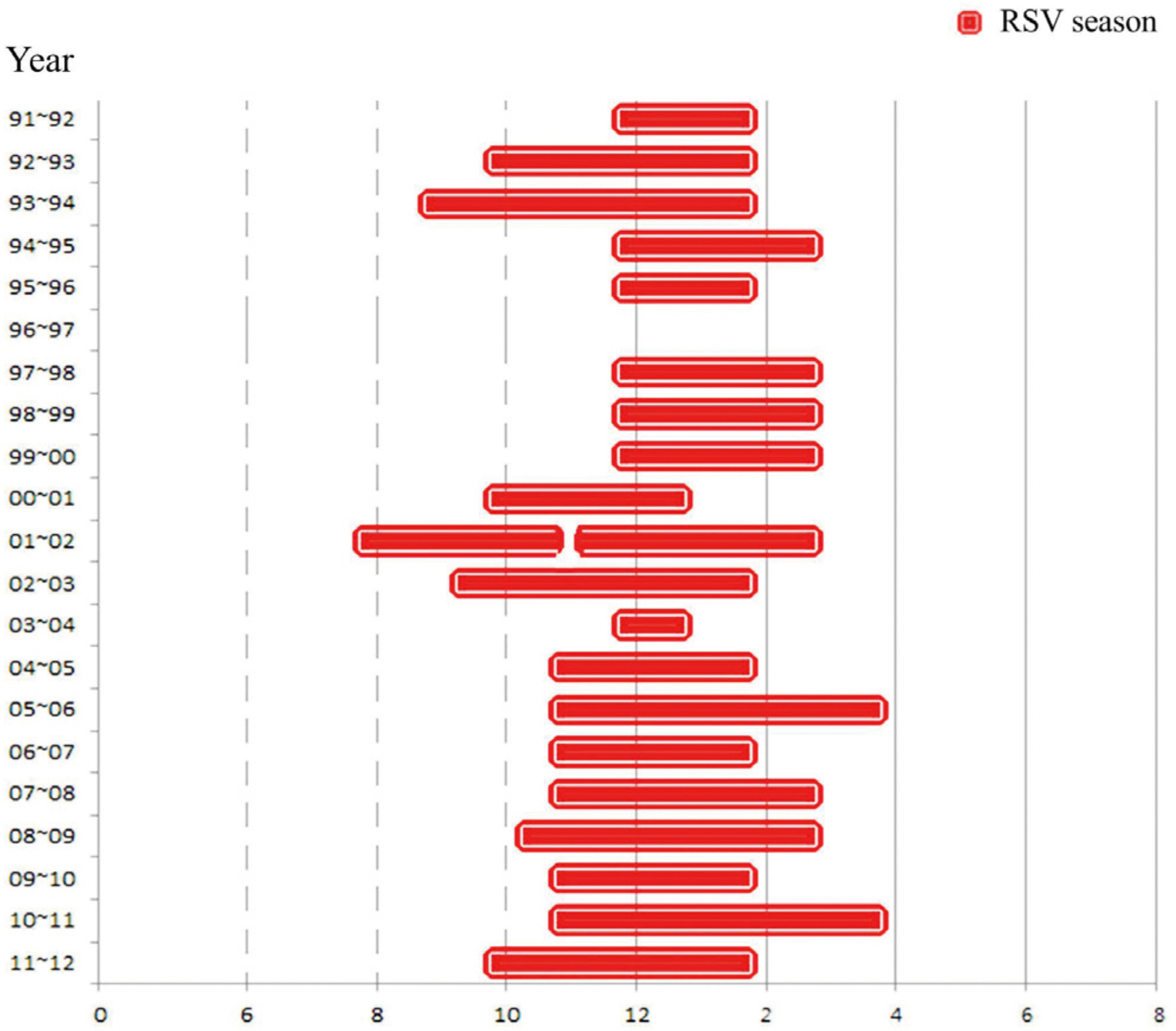

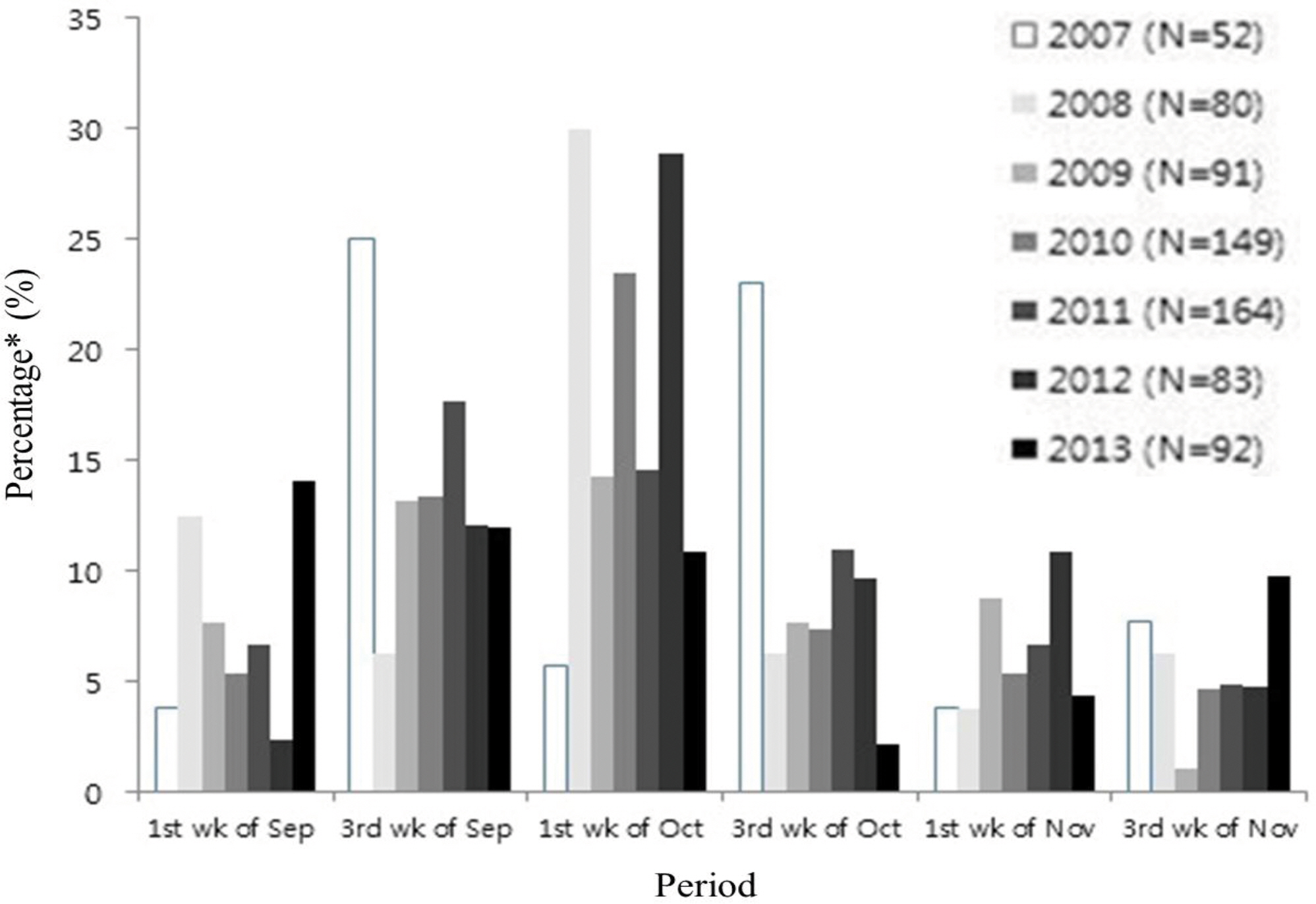

From January 1991 to July 2012, nasopharyngeal (NP) aspirates were obtained from patients who visited Seoul National University Children's Hospital for respiratory symptoms. NP samples were used to detect respiratory viruses. Among them, we analyzed the positive number and detection rate of RSV infection in two-week interval. The beginning of RSV season was defined when RSV positive number was more than 4 and RSV detection rate was over 10%. From January 2007 to March 2014, we analyzed the starting time of palivizumab immunoprophylaxis for the infants at high risk.

RESULTS

The RSV detection rate was 2,013/21,698 (9.69%) over 22 years. The median RSV season was from 2nd-3rd week of October to 1st- 2nd week of February. The earliest starting week was the 3rd week of July in year 2001, and the latest end week was the 3rd week of May in year 1990. Palivizumab immunoprophylaxis was initiated most frequently at the 3rd week of October (18.7%). However, the percentage of starting palivizumab on the 1st week of September has increased from 3.8% in the year 2007 to 14.1% in 2013.

CONCLUSIONS

The year to year variability of RSV season exists. The starting time of palivizumab immunoprophylaxis should be adjusted based on the season of RSV epidemic.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Michaud CM, Murray CI, Bloom BR. Burden of disease-implications for future research. lama. 2001; 285:535–9.

Article2. Paes BA, Mitchell L Banerji A, Lanctot KL, Langley IM. A decade of respiratory syncytial Virus epidemiology and pro—phylaxis: translating evidence into everyday clinical practice. Can Respir J. 2011; 18:610–9.

Article3. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The pre—valence of the respiratory Viruses in the patients with acute respiratory infections, 2012. Public Health Weekly Report. 2013; 6:6.4. Frogel MP, Stewart DL, Hoopes M, Fernandes AW, Mahadevia P]. A systematic review of compliance with palivizumab ad—ministration for RSV immunoprophylaxis. I Manag Care Pharm. 2010; 16:46–58.5. Johnson S, Oliver C, Prince GA, Hemming VG, Pfarr DS, Wang SC, et al. Development of a humanized monoclonal antibody (MEDI—493) with potent in Vitro and in Vivo activity against respiratory syncytial virus. I Infect Dis. 1997; 176:1215–24.

Article6. Romero IR. Palivizumab prophylaxis of respiratory syncytial Virus disease from 1998 to 2002: results from four years of palivizumab usage. Pediatr Infect Dis I. 2003; 22:846–54.7. The IMpact-RSV Study Group. Palivizumab, a humanized respiratory syncytial Virus monoclonal antibody, reduces hospitalization from respiratory syncytial Virus infection in high-risk infants. Pediatrics. 1998; 102:531–7.8. The Korean Pediatric Society. [Immunoprophylaxis for Respiratory Syncytial Virus]. Lee H], editor. Immunization Guideline. 7th ed.Seoul: The Korean Pediatric Society;2012. p. 231–3.9. Panozzo CA, Fowlkes AL, Anderson L]. Variation in timing of respiratory syncytial Virus outbreaks: lessons from national surveillance. Pediatr Infect Dis I. 2007; 26:841–5.10. Mullins IA, Lamonte AC, Bresee IS, Anderson LI. Substantial variability in community respiratory syncytial Virus season timing. Pediatr Infect Dis I. 2003; 22:857–62.

Article11. Respiratory syncytial Virus-United States, July 2007-]une 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011; 60:1203–6.12. McGuiness CB, Boron ML, Saunders B, Edelman L, Kumar VR, Rabon-Stith KM. Respiratory syncytial virus surveillance in the United States, 2007—2012: results from a national sur—veillance system. Pediatr Infect Dis I. 2014; 33:589–94.13. Tatochenko V, Uchaikin V, Gorelov A, Gudkov K, Campbell A, Schulz G, et al. Epidemiology of respiratory syncytial Virus in children ≤2 years of age hospitalized with lower respiratory tract infections in the Russian Federation: 21 pro-spective, multicenter study. Clin Epidemiol. 2010. 2z221–7.14. Fjaerli HO, Farstad T, Bratlid D. Hospitalisations for respiratory syncytial Virus bronchiolitis in Akershus, Norway, 1993-2000: a population-based retrospective study. BMC Pediatr. 2004; 4:25.

Article15. Hsu CH, Lin CY, Chi H, Chang IH, Hung HY, Kao HA, et al. Prolonged seasonality of respiratory syncytial Virus infection among preterm infants in a subtropical climate. PLoS One. 2014; 9:el 10166.

Article16. Prevention of respiratory syncytial Virus infections: indications for the use of palivizumab and update on the use of RSV-IGIV. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases and Committee of Fetus and Newborn. Pediatrics. 1998; 102:1211–6.17. Lambert M. AAP issues updated guidance on palivizumab prophylaxis for RSV infection. Am Fam Physician. 2014; 90:867–8.18. Subramanian KN, Weisman LE, Rhodes T, Ariagno R, Sanchez P], Steichen I, et 211. Safety, tolerance and pharmacokinetics of a humanized monoclonal antibody to respiratory syncytial virus in premature infants and infants with bronchopulmo-nary dysplasia. MEDI-493 Study Group. Pediatr Infect Dis I. 1998; 17:110–5.19. Weinberger DM, Warren IL, Steiner CA, Charu V, Viboud C, Pitzer VE. Reduced—dose schedule of prophylaxis based on local data provides near—optimal protection against respira—tory syncytial virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2015; 61:506–14.

Article20. Weigl IA, Puppe W, Schmitt H. Seasonality of respiratory syncytial virus-positive hospitalizations in children in Kiel, Germany, over a 7 —year period. Infection. 2002; 30:186–92.21. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Weakly occurrence of acute respiratory tract infection With 8 respiratory viruses in Korea patients. Available from:. http://WWW. cdc.g0.kr/kcdchome.22. Park KH, Shin IH, Lee EH, Seo WH, Kim YK, Song D], et al. Seasonal variations of respiratory syncytial Virus infection among the children under 60 months of age with lower re—spiratory tract infections in the capital area, the Republic of Korea, 2008—201 1. I Korean Soc Neonatol. 2012; 19:195–203.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Respiratory syncytial virus prevention in children with congenital heart disease: who and how?

- Outcomes of Palivizumab Prophylaxis for Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Preterm Children with Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia at a Single Hospital in Korea from 2005 to 2009

- Analysis of Palivizumab Prophylaxis in Patients with Acute Lower Respiratory Tract Infection Caused by Respiratory Syncytial Virus

- Clinical Features of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Neonates: A Single Center Study

- Clinical Characteristics and Severity of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Korean Children during the Post-COVID-19 Pandemic Period