Korean J Urol.

2009 Sep;50(9):848-853.

Predictive Factors for Female Bladder Outlet Obstruction Defined by Pressure-Flow Study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Urology, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seongnam, Korea. urojsj@snubh.org

- 2Department of Urology, Seoul Metropolitan Dongbu Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Urology, National Police Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Department of Urology, East-West Neo Medical Center, Kyung Hee University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Abstract

- PURPOSE

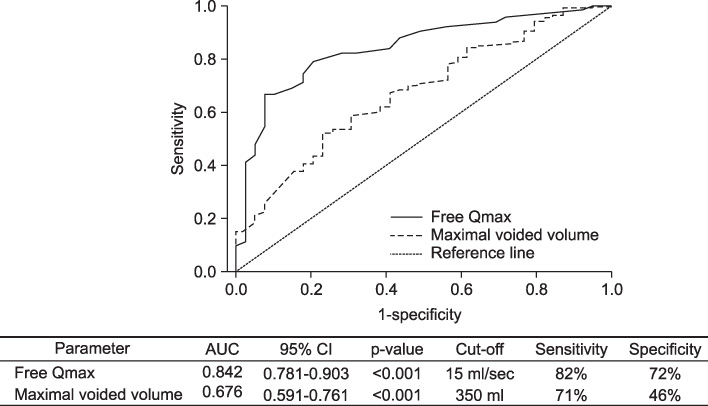

We investigated pre-urodynamic study parameters of bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) defined by pressure-flow study (PFS) in female patients without anatomical obstruction. MATERIALS AND METHODS: The cohort of this study consisted of 320 women who did not have anatomical BOO in whom urodynamic study was conducted for lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). BOO was defined when the PFS maximal flow rate (Qmax) was < or =12 ml/sec and Pdet Qmax was > or =25 cmH2O. The main outcomes were the incidence of BOO and its predictive factors in our cohort. RESULTS: Of the total patients, 39 (12.2%) were diagnosed with BOO in the PFS. Free Qmax and maximal voided volume (MVV) were significant predictors of BOO (p<0.001, p=0.011, respectively) in the multivariate logistic regression. When free Qmax was set to < or =15 ml/sec, its sensitivity and specificity predicting BOO were 82% and 72%, respectively; when MVV was set to < or =350 ml, its values were 71% and 46%, respectively. However, the positive predictive values (PPVs) of free Qmax and MVV were low (34.4% and 28.2%, respectively), whereas the negative predictive values (NPVs) of these parameters were relatively high (96.5% and 91.2%, respectively). CONCLUSIONS: Factors predicting BOO defined by PFS in female patients complaining LUTS without anatomical obstruction were free Qmax and MVV. The PPV of these factors was low, and the NPV was high. Therefore, if free Qmax is >15 ml/sec or MVV is >350 ml, PFS may be not essential. On the contrary, if free Qmax and MVV are below these levels, PFS may be indicated to evaluate the presence of BOO.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Corrin B, Mayor D, Moor T. The pathology of bladder neck obstruction in the female patient. J Urol. 1963. 90:434–439.2. Farrar DJ, Osborne JL, Stephenson TP, Whiteside CG, Weir J, Berry J, et al. A urodynamic view of bladder outflow obstruction in the female: factors influencing the results of treatment. Br J Urol. 1975. 47:815–822.3. Nitti VW, Tu LM, Gitlin J. Diagnosing bladder outlet obstruction in women. J Urol. 1999. 161:1535–1540.4. Kaufman MR, Scarpero H, Dmochowski RR. Diagnosis and management of outlet obstruction in the female. Curr Opin Urol. 2008. 18:365–369.5. Carr LK, Webster GD. Voiding dysfunction following incontinence surgery: diagnosis and treatment with retropubic or vaginal urethrolysis. J Urol. 1997. 157:821–823.6. Groutz A, Blaivas JG, Chaikin DC. Bladder outlet obstruction in women: definition and characteristics. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000. 19:213–220.7. Schäfer W, Abrams P, Liao L, Mattiasson A, Pesce F, Spangberg A, et al. Good urodynamic practices: uroflowmetry, filling cystometry, and pressure-flow studies. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002. 21:261–274.8. Defreitas GA, Zimmern PE, Lemack GE, Shariat SF. Refining diagnosis of anatomic female bladder outlet obstruction: comparison of pressure-flow study parameters in clinically obstructed women with those of normal controls. Urology. 2004. 64:675–679.9. Griffiths DJ. Pressure-flow studies of micturition. Urol Clin North Am. 1996. 23:279–297.10. Chassagne S, Bernier PA, Haab F, Roehrborn CG, Reisch JS, Zimmern PE. Proposed cutoff values to define bladder outlet obstruction in women. Urology. 1998. 51:408–411.11. Lemack GE, Zimmern PE. Pressure flow analysis may aid in identifying women with outflow obstruction. J Urol. 2000. 163:1823–1828.12. Blaivas JG, Groutz A. Bladder outlet obstruction nomogram for women with lower urinary tract symptomatology. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000. 19:553–564.13. Akikwala TV, Fleischman N, Nitti VW. Comparison of diagnostic criteria for female bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol. 2006. 176:2093–2097.14. Kim H, Lee U, Lee M, Choo MS. Cut-off value for bladder outlet obstruction in pressure-flow study in female: a prospective study. Korean J Urol. 2001. 42:1146–1151.15. Raz S, Smith RB. External sphincter spasticity syndrome in female patients. J Urol. 1976. 115:443–446.16. Oelke M, Baard J, Wijkstra H, de la Rosette JJ, Jonas U, Höfner K. Age and bladder outlet obstruction are independently associated with detrusor overactivity in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol. 2008. 54:419–426.17. Im JG, Kim JC, Seo SI, Park YH, Hwang TK. Bladder outlet obstruction in female patients with lower urinary tract symptom. Korean J Urol. 2003. 44:1116–1120.18. Kessler TM, Studer UE, Burkhard FC. The effect of terazosin on functional bladder outlet obstruction in women: a pilot study. J Urol. 2006. 176:1487–1492.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Bladder Outlet Obstruction in the Female Overactive Bladder: Correct Diagnostic Criteria for Bladder Outlet Obstruction?

- Effect of Bladder Outlet Obstruction on Blood Flow and Tissue Collagen in Rat Bladder

- The Clinical Significance of Detrusor Contraction Duration as a Predicting Parameter for Evaluaing Bladder Outlet Obstruction with Lower Urinary Symptoms in Men

- Cut-off Value for Bladder Outlet Obstruction in Pressure-Flow Study in Female: A Prospective Study

- Urodynamic Study on Bladder Outlet Obstruction