Obstet Gynecol Sci.

2013 Jul;56(4):209-216.

The role of placental indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in human pregnancy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan. yoshkudo@hiroshima-u.ac.jp

Abstract

- Munn et al. made a scientific observation of major biological importance. For the first time they showed that in the mammal the fetus does survive an immune attack mounted by the mother, and that the mechanism responsible for the survival depends on the fetus and placenta 'actively' defending itself from attack by maternal T cells by means of an enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (EC 1.13.11.42) dependent localised depletion of L-tryptophan. These findings raise critical questions for disease and its prevention during human pregnancy. Specifically, the role of this mechanism (discovered in mouse) in the human, and the extent to which defective activation of this process is responsible for major clinical diseases are unknown. Therefore some key facts about this enzyme expressed in the human placenta have been studied in order to test whether Munn et al.'s findings in mouse are met for human pregnancy. This short review attempts to describe our experimental work on human placental indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Medawar PB. Some immunological and endocrinological problems raised by the evolution of viviparity in vertebrates. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1953; 7:320–338.2. Bonney EA, Matzinger P. The maternal immune system's interaction with circulating fetal cells. J Immunol. 1997; 158:40–47. PMID: 8977173.3. Hutter H, Hammer A, Dohr G, Hunt JS. HLA expression at the maternal-fetal interface. Dev Immunol. 1998; 6:197–204. PMID: 9814593.

Article4. Munn DH, Zhou M, Attwood JT, Bondarev I, Conway SJ, Marshall B, et al. Prevention of allogeneic fetal rejection by tryptophan catabolism. Science. 1998; 281:1191–1193. PMID: 9712583.

Article5. Yoshida R, Hayaishi O. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Methods Enzymol. 1987; 142:188–195. PMID: 3298973.6. Yamazaki F, Kuroiwa T, Takikawa O, Kido R. Human indolylamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Its tissue distribution, and characterization of the placental enzyme. Biochem J. 1985; 230:635–638. PMID: 3877502.

Article7. Yoshida R, Urade Y, Tokuda M, Hayaishi O. Induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in mouse lung during virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979; 76:4084–4086. PMID: 291064.

Article8. Dai W, Pan H, Kwok O, Dubey JP. Human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase inhibits Toxoplasma gondii growth in fibroblast cells. J Interferon Res. 1994; 14:313–317. PMID: 7897249.9. Dai W, Gupta SL. Molecular cloning, sequencing and expression of human interferon-gamma-inducible indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase cDNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990; 168:1–8. PMID: 2109605.10. Moffett JR, Namboodiri MA. Tryptophan and the immune response. Immunol Cell Biol. 2003; 81:247–265. PMID: 12848846.

Article11. Steckel NK, Kuhn U, Beelen DW, Elmaagacli AH. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in patients with acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation and in pregnant women: association with the induction of allogeneic immune tolerance? Scand J Immunol. 2003; 57:185–191. PMID: 12588666.

Article12. Cady SG, Sono M. 1-Methyl-DL-tryptophan, beta-(3-benzofuranyl)-DL-alanine (the oxygen analog of tryptophan), and beta-[3-benzo(b)thienyl]-DL-alanine (the sulfur analog of tryptophan) are competitive inhibitors for indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991; 291:326–333. PMID: 1952947.13. Pijnenborg R, Anthony J, Davey DA, Rees A, Tiltman A, Vercruysse L, et al. Placental bed spiral arteries in the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991; 98:648–655. PMID: 1883787.

Article14. Davidge ST. Oxidative stress and altered endothelial cell function in preeclampsia. Semin Reprod Endocrinol. 1998; 16:65–73. PMID: 9654609.

Article15. Roberts JM, Taylor RN, Musci TJ, Rodgers GM, Hubel CA, McLaughlin MK. Preeclampsia: an endothelial cell disorder. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989; 161:1200–1204. PMID: 2589440.

Article16. Barden A, Graham D, Beilin LJ, Ritchie J, Baker R, Walters BN, et al. Neutrophil CD11B expression and neutrophil activation in pre-eclampsia. Clin Sci (Lond). 1997; 92:37–44. PMID: 9038589.

Article17. Oian P, Omsjo I, Maltau JM, Osterud B. Increased sensitivity to thromboplastin synthesis in blood monocytes from pre-eclamptic patients. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985; 92:511–517. PMID: 3922396.

Article18. von Dadelszen P, Wilkins T, Redman CW. Maternal peripheral blood leukocytes in normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999; 106:576–581. PMID: 10426616.19. Sacks GP, Studena K, Sargent K, Redman CW. Normal pregnancy and preeclampsia both produce inflammatory changes in peripheral blood leukocytes akin to those of sepsis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998; 179:80–86. PMID: 9704769.

Article20. Kudo Y, Boyd CA, Spyropoulou I, Redman CW, Takikawa O, Katsuki T, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase: distribution and function in the developing human placenta. J Reprod Immunol. 2004; 61:87–98. PMID: 15063632.

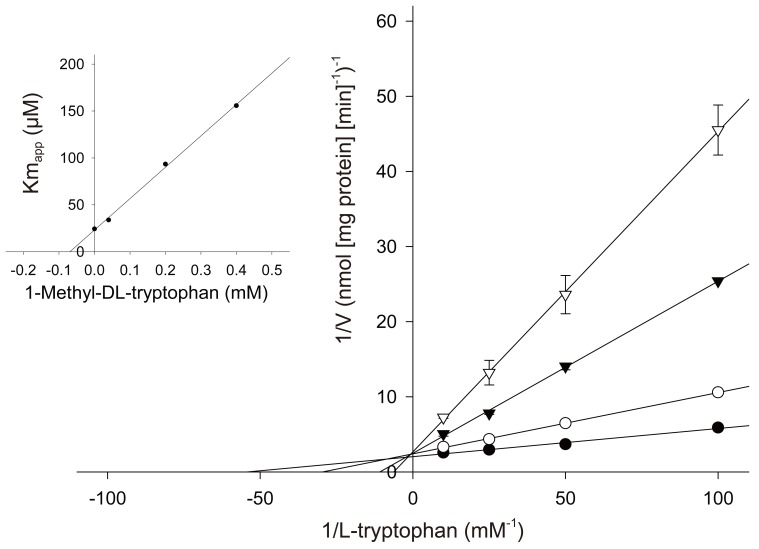

Article21. Kudo Y, Boyd CA. Human placental indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase: cellular localization and characterization of an enzyme preventing fetal rejection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000; 1500:119–124. PMID: 10564724.

Article22. Takikawa O, Habara-Ohkubo A, Yoshida R. IFN-gamma is the inducer of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in allografted tumor cells undergoing rejection. J Immunol. 1990; 145:1246–1250. PMID: 2116480.23. Musso T, Gusella GL, Brooks A, Longo DL, Varesio L. Interleukin-4 inhibits indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in human monocytes. Blood. 1994; 83:1408–1411. PMID: 8118042.

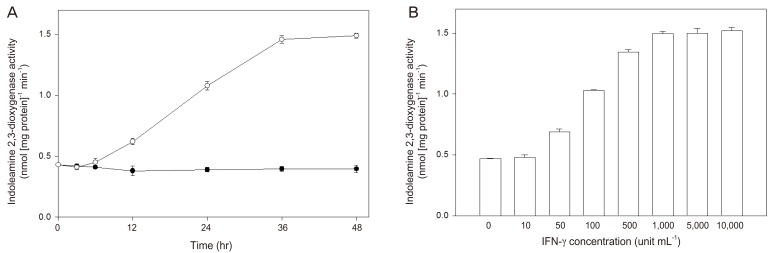

Article24. Kudo Y, Boyd CA, Sargent IL, Redman CW. Modulation of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase by interferon-gamma in human placental chorionic villi. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000; 6:369–374. PMID: 10729320.

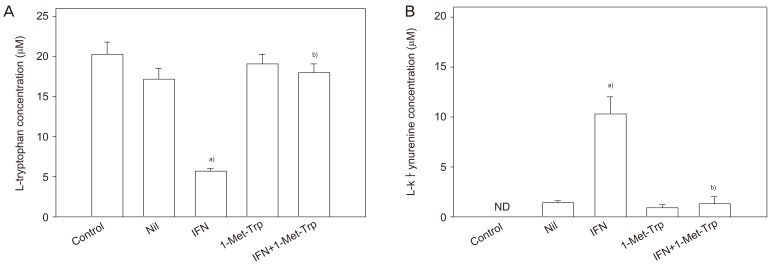

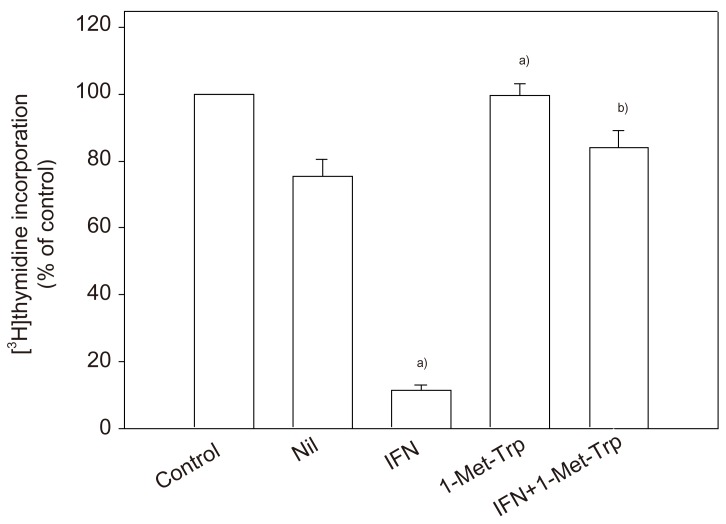

Article25. Kudo Y, Boyd CA. The role of L-tryptophan transport in L-tryptophan degradation by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in human placental explants. J Physiol. 2001; 531:417–423. PMID: 11230514.26. Kudo Y, Boyd CA, Sargent IL, Redman CW. Tryptophan degradation by human placental indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase regulates lymphocyte proliferation. J Physiol. 2001; 535:207–215. PMID: 11507170.

Article27. Redman CW, Sacks GP, Sargent IL. Preeclampsia: an excessive maternal inflammatory response to pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999; 180:499–506. PMID: 9988826.

Article28. Kudo Y, Boyd CA, Sargent IL, Redman CW. Decreased tryptophan catabolism by placental indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 188:719–726. PMID: 12634647.

Article29. Munn DH, Shafizadeh E, Attwood JT, Bondarev I, Pashine A, Mellor AL. Inhibition of T cell proliferation by macrophage tryptophan catabolism. J Exp Med. 1999; 189:1363–1372. PMID: 10224276.

Article30. Thellin O, Coumans B, Zorzi W, Igout A, Heinen E. Tolerance to the foeto-placental 'graft': ten ways to support a child for nine months. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000; 12:731–737. PMID: 11102780.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Expression of Local Immunosuppressive Factor, Indoleamine 2,3-dixygenase, in Human Coreal Cells

- The tryptophan utilization concept in pregnancy

- Suppression of in vitro murine T cell proliferation by human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells is dependent mainly on cyclooxygenase-2 expression

- Proposed Pathway Linking Respiratory Infections with Depression

- Heme-binding-mediated negative regulation of the tryptophan metabolic enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) by IDO2