Nutr Res Pract.

2011 Jun;5(3):224-229.

Effect of processed foods on serum levels of eosinophil cationic protein among children with atopic dermatitis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Food and Nutrition, Hanyang University, 17 Haengdang-dong, Seongdong-gu, Seoul 133-791, Korea. leess@hanyang.ac.kr

- 2Department of Pediatrics, Subdivision of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Chungnam National University Hospital, Daejeon 301-721, Korea.

Abstract

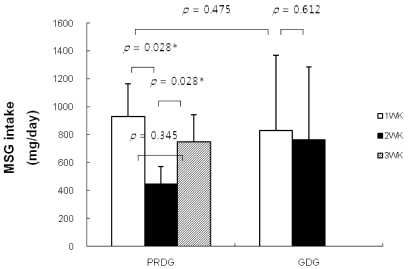

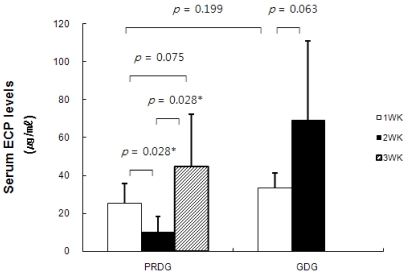

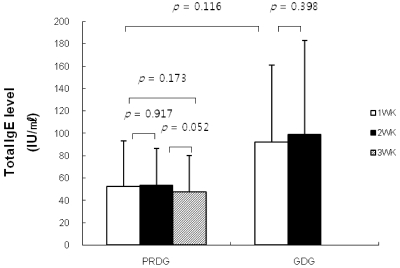

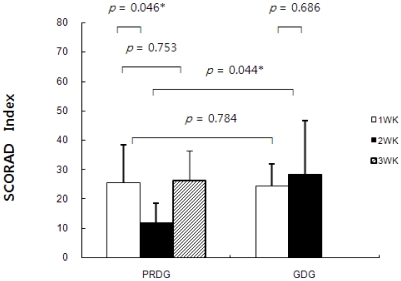

- The prevalence of atopic dermatitis (AD) in school-age children has increased in industrialized countries. As diet is one of the main factors provoking AD, some studies have suggested that food additives in processed foods could function as pseudoallergens, which comprise the non-immunoglobulin E-mediated reaction. Eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) is an eosinophil granule protein released during allergic reactions to food allergens in patients with AD. Thus, serum ECP levels may be a useful indicator of ongoing inflammatory processes in patients with AD. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of consuming MSG in processed foods on serum ECP levels among children with AD. This study was performed with 13 patients with AD (age, 7-11 years) who had a normal range of total IgE levels (< 300 IU/ml). All participants ate normal diets during the first week. Then, six patients were allocated to a processed food-restricted group (PRDG) and seven patients were in a general diet group (GDG). During the second week, children in the PRDG and their parents were asked to avoid eating all processed foods. On the third week, children in the PRDG were allowed all foods, as were the children in the GDG throughout the 3-week period. The subjects were asked to complete a dietary record during the trial period. Children with AD who received the dietary restriction showed decreased consumption of MSG and decreased serum ECP levels and an improved SCORing score on the atopic dermatitis index (P < 0.05). No differences in serum ECP levels or MSG consumption were observed in the GDG. Serum total IgE levels were not changed in either group. In conclusion, a reduction in MSG intake by restricting processed food consumption may lead to a decrease in serum ECP levels in children with AD and improve AD symptoms.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Beasley R. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee. Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. Lancet. 1998; 351:1225–1232. PMID: 9643741.

Article2. von Mutius E. The environmental predictors of allergic disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000; 105:9–19. PMID: 10629447.

Article3. Yoon SP, Kim BS, Lee JH, Lee SC, Kim YK. The environment and lifestyles of atopic dermatitis patients. Korean J Dermatol. 1999; 37:983–991.4. Wilson BG, Bahna SL. Adverse reactions to food additives. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005; 95:499–507. PMID: 16400887.

Article5. Fuglsang G, Madsen C, Saval P, Osterballe O. Prevalence of intolerance to food additives among Danish school children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1993; 4:123–129. PMID: 8220800.

Article6. Fuglsang G, Madsen G, Halken S, Jørgensen S, Ostergaard PA, Osterballe O. Adverse reactions to food additives in children with atopic symptoms. Allergy. 1994; 49:31–37. PMID: 8198237.

Article7. Bischoff S, Crowe SE. Gastrointestinal food allergy: new insights into pathophysiology and clinical perspectives. Gastroenterology. 2005; 128:1089–1113. PMID: 15825090.

Article8. Rancé F. Food allergy in children suffering from atopic eczema. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008; 19:279–284. PMID: 18397414.

Article9. Sampson HA. Update on food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004; 113:805–819. PMID: 15131561.

Article10. Williams AN, Woessner KM. Monosodium glutamate 'allergy': menace or myth? Clin Exp Allergy. 2009; 39:640–646. PMID: 19389112.

Article11. Randhawa S, Bahna SL. Hypersensitivity reactions to food additives. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009; 9:278–283. PMID: 19390435.

Article12. Beyreuther K, Biesalski HK, Fernstrom JD, Grimm P, Hammes WP, Heinemann U, Kempski O, Stehle P, Steinhart H, Walker R. Consensus meeting: monosodium glutamate - an update. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007; 61:304–313. PMID: 16957679.

Article13. Kwok R. Chinese-restaurant syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1968; 278:796.

Article14. Raiten DJ, Talbot JM, Fisher KD. Executive summary from the report: analysis of adverse reactions to monosodium glutamate (MSG). J Nutr. 1995; 125:2891S–2906S. PMID: 7472671.15. Zanda G, Franciosi P, Tognoni G, Rizzo M, Standen SM, Morselli PL, Garattini S. A double blind study on the effects of monosodium glutamate in man. Biomedicine. 1973; 19:202–204.16. Sampson HA, McCaskill CC. Food hypersensitivity and atopic dermatitis: evaluation of 113 patients. J Pediatr. 1985; 107:669–675. PMID: 4056964.

Article17. Johansson SG, Hourihane JO, Bousquet J, Bruijnzeel-Koomen C, Dreborg S, Haahtela T, Kowalski ML, Mygind N, Ring J, van Cauwenberge P, van Hage-Hamsten M, Wüthrich B. EAACI (the European Academy of Allergology and Cinical Immunology) nomenclature task force. A revised nomenclature for allergy. An EAACI position statement from the EAACI nomenclature task force. Allergy. 2001; 56:813–824. PMID: 11551246.

Article18. Johansson SG, Bieber T, Dahl R, Friedmann PS, Lanier BQ, Lockey RF, Motala C, Ortega Martell JA, Platts-Mills TA, Ring J, Thien F, Van Cauwenberge P, Williams HC. Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: Report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004; 113:832–836. PMID: 15131563.

Article19. Warrington RJ, Sauder PJ, McPhillips S. Cell-mediated immune responses to artificial food additives in chronic urticaria. Clin Allergy. 1986; 16:527–533. PMID: 3539408.

Article20. Wardlaw AJ. Eosinophils in the 1990s: new perspectives on their role in health and disease. Postgrad Med J. 1994; 70:536–552. PMID: 7937446.

Article21. Czech W, Krutmann J, Schöpf E, Kapp A. Serum eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) is a sensitive measure for disease activity in atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1992; 126:351–355. PMID: 1571256.

Article22. Furue M, Sugiyama H, Tsukamoto K, Ohtake N, Tamaki K. Serum soluble IL-2 receptor (sIL-2R) and eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) levels in atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 1994; 7:89–95. PMID: 8060919.

Article23. Halmerbauer G, Frischer T, Koller DY. Monitoring of disease activity by measurement of inflammatory markers in atopic dermatitis in childhood. Allergy. 1997; 52:765–769. PMID: 9265994.

Article24. Kägi MK, Joller-Jemelka H, Wüthrich B. Correlation of eosinophils, eosinophil cationic protein and soluble interleukin-2 receptor with the clinical activity of atopic dermatitis. Dermatology. 1992; 185:88–92. PMID: 1421636.25. Paganelli R, Fanales-Belasio E, Carmini D, Scala E, Meglio P, Businco L, Aiuti F. Serum eosinophil cationic protein in patients with atopic dermatitis. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1991; 96:175–178. PMID: 1769747.

Article26. Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1980; 92:44–47.27. Jackola DR, Pierson-Mullany LK, Daniels LR, Corazalla E, Rosenberg A, Blumenthal MN. Robustness into advanced age of atopy-specific mechanisms in atopy-prone families. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003; 58:99–107. PMID: 12586846.

Article28. Zuberbier T, Chantraine-Hess S, Hartmann K, Czarnetzki BM. Pseudoallergen-free diet in the treatment of chronic urticaria. A prospective study. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995; 75:484–487. PMID: 8651031.29. Stalder JF, Taieb A, Atherton DJ, Bieber T, Bonifazi E, Broberg A, Calza A, Coleman R, De Prost Y, Diepgen TL, Gelmetti C, Giannetti A, Harper J, Kunz B, Lachapelle JM, Langeland T, Lever R, Oranje AP, Queille-Roussel C. Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Consensus Report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology. 1993; 186:23–31. PMID: 8435513.30. Juhlin L. Recurrent urticaria: clinical investigation of 330 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1981; 104:369–381. PMID: 7236502.

Article31. Magerl M, Pisarevskaja D, Scheufele R, Zuberbier T, Maurer M. Effects of a pseudoallergen-free diet on chronic spontaneous urticaria: a prospective trial. Allergy. 2010; 65:78–83. PMID: 19796222.

Article32. Yang SH, Kim EJ, Kim YN, Seong KS, Kim SS, Han CK, Lee BH. Comparison of eating habits and dietary intake patterns between people with and without Allergy. Korean J Nutr. 2009; 42:523–535.

Article33. Worm M, Ehlers I, Sterry W, Zuberbier T. Clinical relevance of food additives in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000; 30:407–414. PMID: 10691900.

Article34. Murdoch RD, Pollock I, Young E, Lessof MH. Food additive-induced urticaria: studies of mediator release during provocation tests. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1987; 21:262–266. PMID: 2445986.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Eosinophil Cationic Protein in atopic dermatitis

- Eosinophil Counts in Peripheral Blood, Serum Total IgE, Eosinophil Cationic Protein, IL-4 and Soluble E-selectin in Atopic Dermatitis

- Correlation between the Level of Urinary Leukotriene E4 and Seurm Eosinophil Cationic Protein and Clinical Severity of Atopic Dermatitis in Children

- Comparison of Clinical Severity and Laboratory Results between Atopic and Non-atopic Eczema in Children

- Serum eosinophil cationic protein(ECP) in children with atopic asthma