J Gynecol Oncol.

2011 Jun;22(2):76-82. 10.3802/jgo.2011.22.2.76.

Cervical cancer in the screening era: who fell victim in spite of successful screening programs?

- Affiliations

-

- 1Gynecological Oncology, Radiumhemmet, Department of Oncology, Karolinska University Hospital, Solna, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden. kristina.hellman@ki.se

- 2Division of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Institute for Clinical Science, Karolinska University Hospital, Solna, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden.

- KMID: 2288570

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3802/jgo.2011.22.2.76

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To compare profiles of a prescreening and screening cohort of women with cervical cancer regarding histopathology and clinical variables in order to identify those remaining at risk despite successful screening programs. By analyzing these profiles we hope to improve future screening methods.

METHODS

The prescreening and screening cohorts consisted of 5,046 and 1,174 women, respectively, treated for cervical cancer at the Department of Gynecological Oncology at Radiumhemmet, Karolinska University Hospital, during the periods 1944-1957 and 1990-2004.

RESULTS

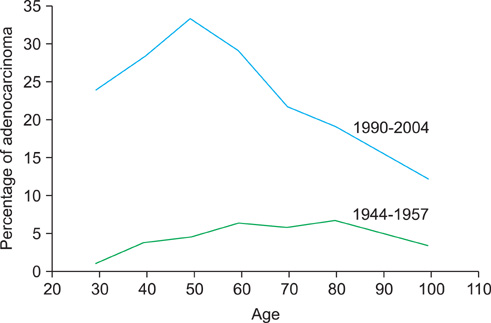

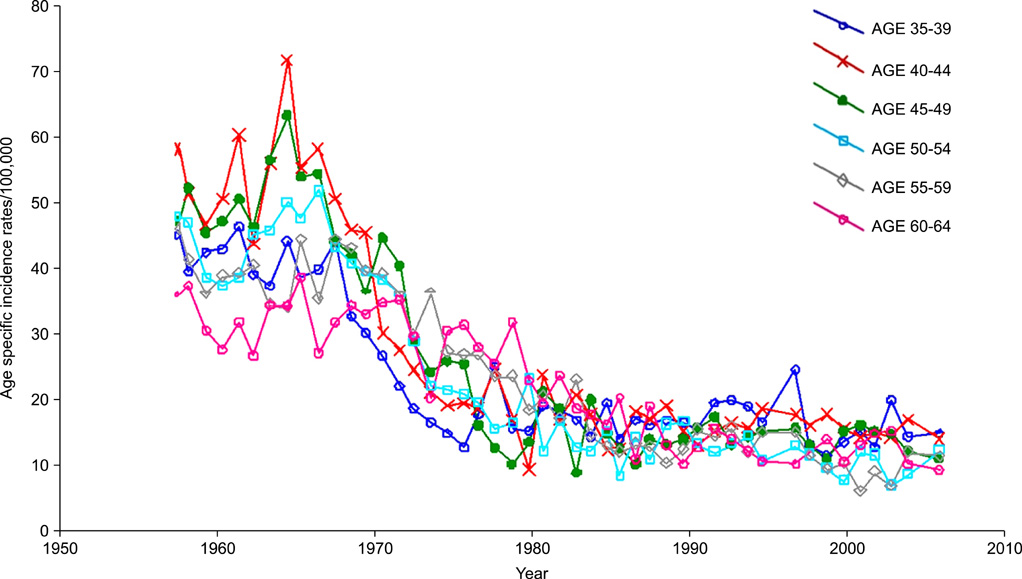

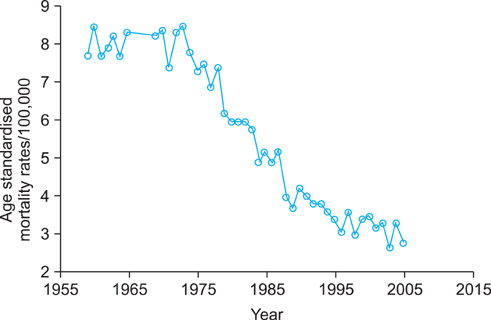

Mean age increased from 48.9 years to 55.3 years in the cohorts treated 1944-1957 and 1990-2004, respectively. The percentage of patients older than 69 years was 5.4% and 27.3% in the prescreening and screening period, respectively. A shift towards earlier stages at diagnosis, a reduction of squamous cervical cancer and an increase of adenocarcinoma were observed in the screening cohort. The percentage of adenocarcinoma was about 6 times higher among younger patients. Cases of stump cancer and cervical cancer associated with pregnancy have declined. Eighty-seven women in the screening cohort had a history of treatment for in situ carcinoma by conization; 28% of these cases developed cervical cancer within one year after conization.

CONCLUSION

The profile changed in the screening era indicating a need to refine screening for improved detection of in older women. This study, one of the largest clinical series of cervical cancer, provides an important baseline with which later studies can be compared to evaluate the effects of human papillomavirus vaccine and other important changes in this field.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Tailoring radicality in early cervical cancer: how far can we go?

Jacobus van der Velden, Constantijne H. Mom

J Gynecol Oncol. 2019;30(1):. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2019.30.e30.

Reference

-

1. Boyes DA, Knowelden J, Phillips AJ. The evaluation of cancer control measures. Br J Cancer. 1973. 28:105–107.2. Christopherson WM, Parker JE, Mendez WM, Lundin FE Jr. Cervix cancer death rates and mass cytologic screening. Cancer. 1970. 26:808–811.3. Dillner J. Cervical cancer screening in Sweden. Eur J Cancer. 2000. 36:2255–2259.4. Pettersson F, Bjorkholm E, Naslund I. Evaluation of screening for cervical cancer in Sweden: trends in incidence and mortality 1958-1980. Int J Epidemiol. 1985. 14:521–527.5. Pettersson F, Naslund I, Malker B. Evaluation of the effect of Papanicolaou screening in Sweden: record linkage between a central screening registry and the National Cancer Registry. IARC Sci Publ. 1986. (76):91–105.6. The National Board of Health and Welfare. Statistics Sweden. 1976. Stockholm: The National Board of Health and Welfare.7. Pettersson F. Kavanagh JJ, Singletary SE, Einhorn N, DePetrillo AD, editors. Secondary prevention: screening for carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Cancer in women. 1998. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Science;240–250.8. The National Board of Health and Welfare. Cancer Incidence in Sweden 2008. 2009. Stockholm: The National Board of Health and Welfare.9. Pettersson F. Annual report on the results of treatment in gynecologic cancer FIGO 1994. 1995. Stockholm: Radiumhemmet.10. World Health Organization. Use of screening for cervical cancer: cervical cancer screening. 2005. Lyon: IARC Press.11. Bulk S, Visser O, Rozendaal L, Verheijen RH, Meijer CJ. Cervical cancer in the Netherlands 1989-1998: decrease of squamous cell carcinoma in older women, increase of adenocarcinoma in younger women. Int J Cancer. 2005. 113:1005–1009.12. Socialstyrelsen: Statistics of Sweden [Internet]. The National Board of Health and Welfare. cited 2011 May 20. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen;Available from: http://www.sos.se.13. International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer. Appleby P, Beral V, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Colin D, Franceschi S, et al. Carcinoma of the cervix and tobacco smoking: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 13,541 women with carcinoma of the cervix and 23,017 women without carcinoma of the cervix from 23 epidemiological studies. Int J Cancer. 2006. 118:1481–1495.14. Berrington de Gonzalez A, Sweetland S, Green J. Comparison of risk factors for squamous cell and adenocarcinomas of the cervix: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2004. 90:1787–1791.15. Plummer M, Herrero R, Franceschi S, Meijer CJ, Snijders P, Bosch FX, et al. Smoking and cervical cancer: pooled analysis of the IARC multi-centric case-control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2003. 14:805–814.16. Pettersson BF. Adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Changes in incidence. A cancer registry study [abstract]. Paper presented at: 38th Annual Meeting of the Society of Pelvic Surgeons. October 5-8, 1988; Toronto, ON.17. Bergstrom R, Sparen P, Adami HO. Trends in cancer of the cervix uteri in Sweden following cytological screening. Br J Cancer. 1999. 81:159–166.18. Sasieni P, Adams J. Changing rates of adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma of the cervix in England. Lancet. 2001. 357:1490–1493.19. Sasieni P, Castanon A, Cuzick J. Screening and adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Int J Cancer. 2009. 125:525–529.20. Bray F, Carstensen B, Moller H, Zappa M, Zakelj MP, Lawrence G, et al. Incidence trends of adenocarcinoma of the cervix in 13 European countries. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005. 14:2191–2199.21. Babes A. Diagnostic du cancer du col uterin par Les-Frottis. Presse Med. 1928. 36:451–454.22. Naslund I, Auer G, Pettersson F, Sjovall K. Evaluation of the pulse wash sampling technique for screening of uterine cervical carcinoma. Acta Radiol Oncol. 1986. 25:131–136.23. Zielinski GD, Snijders PJ, Rozendaal L, Daalmeijer NF, Risse EK, Voorhorst FJ, et al. The presence of high-risk HPV combined with specific p53 and p16INK4a expression patterns points to high-risk HPV as the main causative agent for adenocarcinoma in situ and adenocarcinoma of the cervix. J Pathol. 2003. 201:535–543.24. Brismar S, Johansson B, Borjesson M, Arbyn M, Andersson S. Follow-up after treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia by human papillomavirus genotyping. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009. 201:17.e1–17.e8.25. Gustafsson L, Sparen P, Gustafsson M, Pettersson B, Wilander E, Bergstrom R, et al. Low efficiency of cytologic screening for cancer in situ of the cervix in older women. Int J Cancer. 1995. 63:804–809.26. Gyllensten U, Lindell M, Gustafsson I, Wilander E. HPV test shows low sensitivity of Pap screen in older women. Lancet Oncol. 2010. 11:509–510.27. Andrae B, Kemetli L, Sparen P, Silfverdal L, Strander B, Ryd W, et al. Screening-preventable cervical cancer risks: evidence from a nationwide audit in Sweden. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008. 100:622–629.28. Anttila A, Ronco G. Working Group on the Registration and Monitoring of Cervical Cancer Screening Programmes in the European Union; within the European Network for Information on Cancer (EUNICE). Description of the national situation of cervical cancer screening in the member states of the European Union. Eur J Cancer. 2009. 45:2685–2708.29. Clegg LX, Reichman ME, Miller BA, Hankey BF, Singh GK, Lin YD, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status on cancer incidence and stage at diagnosis: selected findings from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results: National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2009. 20:417–435.30. Jensen KE, Hannibal CG, Nielsen A, Jensen A, Nohr B, Munk C, et al. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from cancer of the female genital organs in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer. 2008. 44:2003–2017.31. van der Aa MA, Siesling S, Louwman MW, Visser O, Pukkala E, Coebergh JW. Geographical relationships between sociodemographic factors and incidence of cervical cancer in the Netherlands 1989-2003. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008. 17:453–459.32. Eaker S, Adami HO, Sparen P. Reasons women do not attend screening for cervical cancer: a population-based study in Sweden. Prev Med. 2001. 32:482–491.33. Idestrom M, Milsom I, Andersson-Ellstrom A. Knowledge and attitudes about the Pap-smear screening program: a population-based study of women aged 20-59 years. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002. 81:962–967.34. Pettersson F, Malker B. Invasive carcinoma of the uterine cervix following diagnosis and treatment of in situ carcinoma: record linkage study within a National Cancer Registry. Radiother Oncol. 1989. 16:115–120.35. Hellstrom AC, Sigurjonson T, Pettersson F. Carcinoma of the cervical stump. The radiumhemmet series 1959-1987: treatment and prognosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001. 80:152–157.36. Pettersson BF, Andersson S, Hellman K, Hellstrom AC. Invasive carcinoma of the uterine cervix associated with pregnancy: 90 years of experience. Cancer. 2010. 116:2343–2349.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Cost-benefit issues about human papillomavirus (HPV) testing

- Proposal for cervical cancer screening in the era of HPV vaccination

- New insights into cervical cancer screening

- Epidemiologic characteristics of cervical cancer in Korean women

- Cervical screening among Chinese females in the era of HPV vaccination: a population-based survey on screening uptake and regular screening following an 18-year organized screening program