Obstet Gynecol Sci.

2018 May;61(3):298-308. 10.5468/ogs.2018.61.3.298.

Proposal for cervical cancer screening in the era of HPV vaccination

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Guro Hospital, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. jklee38@korea.ac.kr

- KMID: 2416117

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5468/ogs.2018.61.3.298

Abstract

- Eradication of cervical cancer involves the expansion of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine coverage and the development of efficient screening guidelines that take vaccination into account. In Korea, the HPV National Immunization Program was launched in 2016 and is expected to shift the prevalence of HPV genotypes in the country, among other effects. The experiences of another countries that implement national immunization programs should be applied to Korea. If HPV vaccines spread nationwide with broader coverage, after a few decades, cervical intraepithelial lesions or invasive cancer should become a rare disease, leading to a predictable decrease in the positive predictive value of cervical screening cytology. HPV testing is the primary screening tool for cervical cancer and has replaced traditional cytology-based guidelines. The current screening strategy in Korea does not differentiate women who have received complete vaccination from those who are unvaccinated. However, in the post-vaccination era, newly revised policies will be needed. We also discuss on how to increase the vaccination rate in adolescence.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Knowledge, attitude, practice, and self-efficacy of women regarding cervical cancer screening

Shahnaz Ghalavandi, Alireza Heidarnia, Fatemeh Zarei, Reza Beiranvand

Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2021;64(2):216-225. doi: 10.5468/ogs.20236.Type-Specific Viral Load and Physical State of HPV Type 16, 18, and 58 as Diagnostic Biomarkers for High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions or Cervical Cancer

Jongseung Kim, Bu Kyung Kim, Dongsoo Jeon, Chae Hyeong Lee, Ju-Won Roh, Joo-Young Kim, Sang-Yoon Park

Cancer Res Treat. 2020;52(2):396-405. doi: 10.4143/crt.2019.152.

Reference

-

1. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015; 65:87–108.

Article2. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012: estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012 v1.0 [Internet]. Lyon: IARC;2013. cited 2017 Aug 1. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Default.aspx.3. Vaccarella S, Franceschi S, Engholm G, Lönnberg S, Khan S, Bray F. 50 years of screening in the Nordic countries: quantifying the effects on cervical cancer incidence. Br J Cancer. 2014; 111:965–969.

Article4. Vaccarella S, Franceschi S, Zaridze D, Poljak M, Veerus P, Plummer M, et al. Preventable fractions of cervical cancer via effective screening in six Baltic, central, and eastern European countries 2017–40: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2016; 17:1445–1452.

Article5. Jung KW, Won YJ, Oh CM, Kong HJ, Lee DH, Lee KH. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2014. Cancer Res Treat. 2017; 49:292–305.

Article6. de Sanjose S, Quint WG, Alemany L, Geraets DT, Klaustermeier JE, Lloveras B, et al. Human papillomavirus genotype attribution in invasive cervical cancer: a retrospective cross-sectional worldwide study. Lancet Oncol. 2010; 11:1048–1056.7. Sycuro LK, Xi LF, Hughes JP, Feng Q, Winer RL, Lee SK, et al. Persistence of genital human papillomavirus infection in a long-term follow-up study of female university students. J Infect Dis. 2008; 198:971–978.

Article8. Koshiol J, Lindsay L, Pimenta JM, Poole C, Jenkins D, Smith JS. Persistent human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2008; 168:123–137.

Article9. Forman D, de Martel C, Lacey CJ, Soerjomataram I, Lortet-Tieulent J, Bruni L, et al. Global burden of human papillomavirus and related diseases. Vaccine. 2012; 30:Suppl 5. F12–F23.

Article10. Bouscarat F, Pelletier F, Fouere S, Janier M, Bertolloti A, Aubin F, et al. External genital warts (condylomata). Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2016; 143:741–745.11. Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, Confortini M, Dalla Palma P, Del Mistro A, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010; 11:249–257.

Article12. Leinonen M, Nieminen P, Kotaniemi-Talonen L, Malila N, Tarkkanen J, Laurila P, et al. Age-specific evaluation of primary human papillomavirus screening vs conventional cytology in a randomized setting. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009; 101:1612–1623.

Article13. Almonte M, Sasieni P, Cuzick J. Incorporating human papillomavirus testing into cytological screening in the era of prophylactic vaccines. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011; 25:617–629.

Article14. Santin AD, Bellone S, Palmieri M, Zanolini A, Ravaggi A, Siegel ER, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 and 18 E7-pulsed dendritic cell vaccination of stage IB or IIA cervical cancer patients: a phase I escalating-dose trial. J Virol. 2008; 82:1968–1979.

Article15. Mészner Z, Jankovics I, Nagy A, Gerlinger I, Katona G. Recurrent laryngeal papillomatosis with oesophageal involvement in a 2 year old boy: successful treatment with the quadrivalent human papillomatosis vaccine. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015; 79:262–266.

Article16. Yu Z. Recurrent laryngeal papillomatosis: the current treatment and future development. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2015; 29:2107–2110.17. Luxembourg A, Brown D, Bouchard C, Giuliano AR, Iversen OE, Joura EA, et al. Phase II studies to select the formulation of a multivalent HPV L1 virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015; 11:1313–1322.

Article18. Garçon N, Morel S, Didierlaurent A, Descamps D, Wettendorff M, Van Mechelen M. Development of an AS04-adjuvanted HPV vaccine with the adjuvant system approach. BioDrugs. 2011; 25:217–226.

Article19. Yokomine M, Matsueda S, Kawano K, Sasada T, Fukui A, Yamashita T, et al. Enhancement of humoral and cell mediated immune response to HPV16 L1-derived peptides subsequent to vaccination with prophylactic bivalent HPV L1 virus-like particle vaccine in healthy females. Exp Ther Med. 2017; 13:1500–1505.

Article20. Markowitz LE, Liu G, Hariri S, Steinau M, Dunne EF, Unger ER. Prevalence of HPV after introduction of the vaccination program in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016; 137:e20151968.

Article21. Naud PS, Roteli-Martins CM, De Carvalho NS, Teixeira JC, de Borba PC, Sanchez N, et al. Sustained efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: final analysis of a long-term follow-up study up to 9.4 years post-vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014; 10:2147–2162.22. Hildesheim A, Wacholder S, Catteau G, Struyf F, Dubin G, Herrero R, et al. Efficacy of the HPV-16/18 vaccine: final according to protocol results from the blinded phase of the randomized Costa Rica HPV-16/18 vaccine trial. Vaccine. 2014; 32:5087–5097.

Article23. Paavonen J, Naud P, Salmeron J, Wheeler CM, Chow SN, Apter D, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by oncogenic HPV types (PATRICIA): final analysis of a double-blind, randomised study in young women. Lancet. 2009; 374:301–314.24. FUTURE II Study Group. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356:1915–1927.25. Joura EA, Giuliano AR, Iversen OE, Bouchard C, Mao C, Mehlsen J, et al. A 9-valent HPV vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:711–723.

Article26. Villa LL, Ault KA, Giuliano AR, Costa RL, Petta CA, Andrade RP, et al. Immunologic responses following administration of a vaccine targeting human papillomavirus types 6, 11, 16, and 18. Vaccine. 2006; 24:5571–5583.

Article27. Hariri S, Johnson ML, Bennett NM, Bauer HM, Park IU, Schafer S, et al. Population-based trends in high-grade cervical lesions in the early human papillomavirus vaccine era in the United States. Cancer. 2015; 121:2775–2781.

Article28. Petrosky EY, Hariri S, Markowitz LE, Panicker G, Unger ER, Dunne EF. Is vaccine type seropositivity a marker for human papillomavirus vaccination? National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003–2010. Int J Infect Dis. 2015; 33:137–141.

Article29. Mesher D, Stanford E, White J, Findlow J, Warrington R, Das S, et al. HPV serology testing confirms high HPV immunisation coverage in England. PLoS One. 2016; 11:e0150107.

Article30. Carter JJ, Koutsky LA, Hughes JP, Lee SK, Kuypers J, Kiviat N, et al. Comparison of human papillomavirus types 16, 18, and 6 capsid antibody responses following incident infection. J Infect Dis. 2000; 181:1911–1919.

Article31. Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler CM, Moscicki AB, Romanowski B, Roteli-Martins CM, et al. Sustained efficacy up to 4.5 years of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine against human papillomavirus types 16 and 18: follow-up from a randomised control trial. Lancet. 2006; 367:1247–1255.

Article32. Olsson SE, Villa LL, Costa RL, Petta CA, Andrade RP, Malm C, et al. Induction of immune memory following administration of a prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) types 6/11/16/18 L1 virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine. Vaccine. 2007; 25:4931–4939.

Article33. Fischer S, Bettstetter M, Becher A, Lessel M, Bank C, Krams M, et al. Shift in prevalence of HPV types in cervical cytology specimens in the era of HPV vaccination. Oncol Lett. 2016; 12:601–610.

Article34. Kavanagh K, Pollock KG, Potts A, Love J, Cuschieri K, Cubie H, et al. Introduction and sustained high coverage of the HPV bivalent vaccine leads to a reduction in prevalence of HPV 16/18 and closely related HPV types. Br J Cancer. 2014; 110:2804–2811.

Article35. Bhatia R, Kavanagh K, Cubie HA, Serrano I, Wennington H, Hopkins M, et al. Use of HPV testing for cervical screening in vaccinated women--Insights from the SHEVa (Scottish HPV Prevalence in Vaccinated Women) study. Int J Cancer. 2016; 138:2922–2931.

Article36. Bae JH, Lee SJ, Kim CJ, Hur SY, Park YG, Lee WC, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) type distribution in Korean women: a meta-analysis. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008; 18:788–794.37. Lee HS, Kim KM, Kim SM, Choi YD, Nam JH, Park CS, et al. Human papillomavirus genotyping using HPV DNA chip analysis in Korean women. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007; 17:497–501.

Article38. Kim MJ, Kim JJ, Kim S. Type-specific prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus by cervical cytology and age: data from the health check-ups of 7,014 Korean women. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013; 56:110–120.

Article39. So KA, Hong JH, Lee JK. Human papillomavirus prevalence and type distribution among 968 women in South Korea. J Cancer Prev. 2016; 21:104–109.

Article40. Oh JK, Alemany L, Suh JI, Rha SH, Munoz N, Bosch FX, et al. Type-specific human papillomavirus distribution in invasive cervical cancer in Korea, 1958–2004. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010; 11:993–1000.41. Jun JK, Choi KS, Jung KW, Lee HY, Gapstur SM, Park EC, et al. Effectiveness of an organized cervical cancer screening program in Korea: results from a cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2009; 124:188–193.

Article42. Dickinson J, Tsakonas E, Conner Gorber S, Lewin G, Shaw E, Singh H, et al. Recommendations on screening for cervical cancer. CMAJ. 2013; 185:35–45.43. Moyer VA. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012; 156:880–891. W312.

Article44. Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, Killackey M, Kulasingam SL, Cain J, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012; 137:516–542.

Article45. Lee JK, Hong JH, Kang S, Kim DY, Kim BG, Kim SH, et al. Practice guidelines for the early detection of cervical cancer in Korea: Korean Society of Gynecologic Oncology and the Korean Society for Cytopathology 2012 edition. J Gynecol Oncol. 2013; 24:186–203.

Article46. Min KJ, Lee YJ, Suh M, Yoo CW, Lim MC, Choi J, et al. The Korean guideline for cervical cancer screening. J Gynecol Oncol. 2015; 26:232–239.

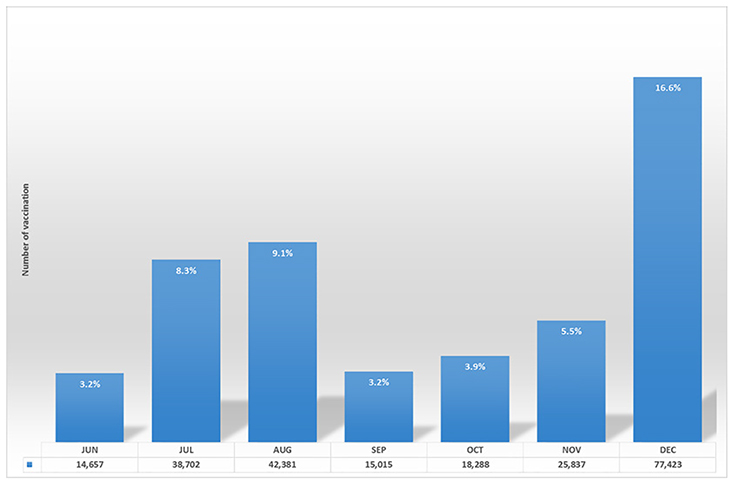

Article47. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cheif of KCDC, conference of public health and ministry of education was held in Gokseong where had the highest HPV vaccination rate (press release in 25th April, 2017). Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2017.48. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National immunization program "Up to 3 times difference" regional disparity in HPV NIP vaccination rate (press release in June 2017). Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2017.49. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National immunization program [Internet]. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2017. updated 2017 Jun 9. cited 2017 Jul 10. Available from: https://nip.cdc.go.kr/irgd/index.html.50. Wheeler CM, Castellsagué X, Garland SM, Szarewski A, Paavonen J, Naud P, et al. Cross-protective efficacy of HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by non-vaccine oncogenic HPV types: 4-year end-of-study analysis of the randomised, double-blind PATRICIA trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012; 13:100–110.51. Tabrizi SN, Brotherton JM, Kaldor JM, Skinner SR, Liu B, Bateson D, et al. Assessment of herd immunity and cross-protection after a human papillomavirus vaccination programme in Australia: a repeat cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014; 14:958–966.

Article52. Woestenberg PJ, King AJ, van der Sande MA, Donken R, Leussink S, van der Klis FR, et al. No evidence for cross-protection of the HPV-16/18 vaccine against HPV-6/11 positivity in female STI clinic visitors. J Infect. 2017; 74:393–400.53. Westra TA, Stirbu-Wagner I, Dorsman S, Tutuhatunewa ED, de Vrij EL, Nijman HW, et al. Inclusion of the benefits of enhanced cross-protection against cervical cancer and prevention of genital warts in the cost-effectiveness analysis of human papillomavirus vaccination in the Netherlands. BMC Infect Dis. 2013; 13:75.

Article54. Howell-Jones R, Soldan K, Wetten S, Mesher D, Williams T, Gill ON, et al. Declining genital Warts in young women in england associated with HPV 16/18 vaccination: an ecological study. J Infect Dis. 2013; 208:1397–1403.

Article55. Tota JE, Struyf F, Merikukka M, Gonzalez P, Kreimer AR, Bi D, et al. Evaluation of type replacement following HPV16/18 vaccination: pooled analysis of two randomized trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017; 109:djw300.

Article56. Chao C, Silverberg MJ, Becerra TA, Corley DA, Jensen CD, Chen Q, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination and subsequent cervical cancer screening in a large integrated healthcare system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 216:151.e1–151.e9.

Article57. Hirth JM, Lin YL, Kuo YF, Berenson AB. Effect of number of human papillomavirus vaccine doses on guideline adherent cervical cytology screening among 19–26 year old females. Prev Med. 2016; 88:134–139.

Article58. Wright TC Jr, Stoler MH, Sharma A, Zhang G, Behrens C, Wright TL, et al. Evaluation of HPV-16 and HPV-18 genotyping for the triage of women with high-risk HPV+ cytology-negative results. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011; 136:578–586.

Article59. Khan MJ, Castle PE, Lorincz AT, Wacholder S, Sherman M, Scott DR, et al. The elevated 10-year risk of cervical precancer and cancer in women with human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 or 18 and the possible utility of type-specific HPV testing in clinical practice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005; 97:1072–1079.

Article60. Castle PE, Rodríguez AC, Burk RD, Herrero R, Wacholder S, Alfaro M, et al. Short term persistence of human papillomavirus and risk of cervical precancer and cancer: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2009; 339:b2569.

Article61. Jeronimo J, Castle PE, Temin S, Shastri SS. Secondary prevention of cervical cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology resource-stratified clinical practice guideline summary. J Oncol Pract. 2017; 13:129–133.

Article62. Giorgi Rossi P, Carozzi F, Federici A, Ronco G, Zappa M, Franceschi S, et al. Cervical cancer screening in women vaccinated against human papillomavirus infection: Recommendations from a consensus conference. Prev Med. 2017; 98:21–30.

Article63. Kim JJ, Burger EA, Sy S, Campos NG. Optimal cervical cancer screening in women vaccinated against human papillomavirus. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017; 109:djw216.

Article64. Meijer CJ, Berkhof J, Castle PE, Hesselink AT, Franco EL, Ronco G, et al. Guidelines for human papillomavirus DNA test requirements for primary cervical cancer screening in women 30 years and older. Int J Cancer. 2009; 124:516–520.

Article65. Franco EL, Cuzick J, Hildesheim A, de Sanjosé S. Chapter 20: Issues in planning cervical cancer screening in the era of HPV vaccination. Vaccine. 2006; 24:Suppl 3. S3/171-7.

Article66. Cuzick J, Clavel C, Petry KU, Meijer CJ, Hoyer H, Ratnam S, et al. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2006; 119:1095–1101.

Article67. Kusanagi Y, Kojima A, Mikami Y, Kiyokawa T, Sudo T, Yamaguchi S, et al. Absence of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) detection in endocervical adenocarcinoma with gastric morphology and phenotype. Am J Pathol. 2010; 177:2169–2175.

Article68. Palmer TJ, McFadden M, Pollock KG, Kavanagh K, Cuschieri K, Cruickshank M, et al. HPV immunisation and cervical screening--confirmation of changed performance of cytology as a screening test in immunised women: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2016; 114:582–589.

Article69. Valdez M, Jeronimo J, Bansil P, Qiao YL, Zhao FH, Chen W, et al. Effectiveness of novel, lower cost molecular human papillomavirus-based tests for cervical cancer screening in rural china. Int J Cancer. 2016; 138:1453–1461.

Article70. Zhao FH, Jeronimo J, Qiao YL, Schweizer J, Chen W, Valdez M, et al. An evaluation of novel, lower-cost molecular screening tests for human papillomavirus in rural China. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2013; 6:938–948.

Article71. Carozzi F, Gillio-Tos A, Confortini M, Del Mistro A, Sani C, De Marco L, et al. Risk of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia during follow-up in HPV-positive women according to baseline p16-INK4A results: a prospective analysis of a nested substudy of the NTCC randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013; 14:168–176.

Article72. Carozzi F, Confortini M, Dalla Palma P, Del Mistro A, Gillio-Tos A, De Marco L, et al. Use of p16-INK4A overexpression to increase the specificity of human papillomavirus testing: a nested substudy of the NTCC randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008; 9:937–945.

Article73. Uijterwaal MH, Polman NJ, Witte BI, van Kemenade FJ, Rijkaart D, Berkhof J, et al. Triaging HPV-positive women with normal cytology by p16/Ki-67 dual-stained cytology testing: baseline and longitudinal data. Int J Cancer. 2015; 136:2361–2368.

Article74. Wright TC Jr, Behrens CM, Ranger-Moore J, Rehm S, Sharma A, Stoler MH, et al. Triaging HPV-positive women with p16/Ki-67 dual-stained cytology: Results from a sub-study nested into the ATHENA trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2017; 144:51–56.

Article75. Wentzensen N, Schwartz L, Zuna RE, Smith K, Mathews C, Gold MA, et al. Performance of p16/Ki-67 immunostaining to detect cervical cancer precursors in a colposcopy referral population. Clin Cancer Res. 2012; 18:4154–4162.

Article76. Kreimer AR, Struyf F, Del Rosario-Raymundo MR, Hildesheim A, Skinner SR, Wacholder S, et al. Efficacy of fewer than three doses of an HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: combined analysis of data from the Costa Rica Vaccine and PATRICIA Trials. Lancet Oncol. 2015; 16:775–786.

Article77. Winer RL, Gonzales AA, Noonan CJ, Buchwald DS. A Cluster-randomized trial to evaluate a mother-daughter dyadic educational intervention for increasing HPV vaccination coverage in American Indian girls. J Community Health. 2016; 41:274–281.

Article78. Krantz L, Ollberding NJ, Beck AF, Carol Burkhardt M. Increasing HPV vaccination coverage through provider-based interventions. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2018; 57:319–326.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Cervical screening among Chinese females in the era of HPV vaccination: a population-based survey on screening uptake and regular screening following an 18-year organized screening program

- Current status of cervical cancer and HPV infection in Korea

- Cervical cancer in Thailand: 2023 update

- Issues on Current HPV Vaccination in Korea and Proposal Statement

- Human Papillomavirus Vaccine