Korean J Obstet Gynecol.

2011 Jun;54(6):300-303. 10.5468/KJOG.2011.54.6.300.

Fetal survival after emergent cesarean section for umbilical cord prolapse with propofol anesthesia in case of anesthesiologist and pediatrician unavailable: A case report

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Queensmedi Hospital, Seoul, Korea. sonny42@hanmail.net

- KMID: 2274038

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5468/KJOG.2011.54.6.300

Abstract

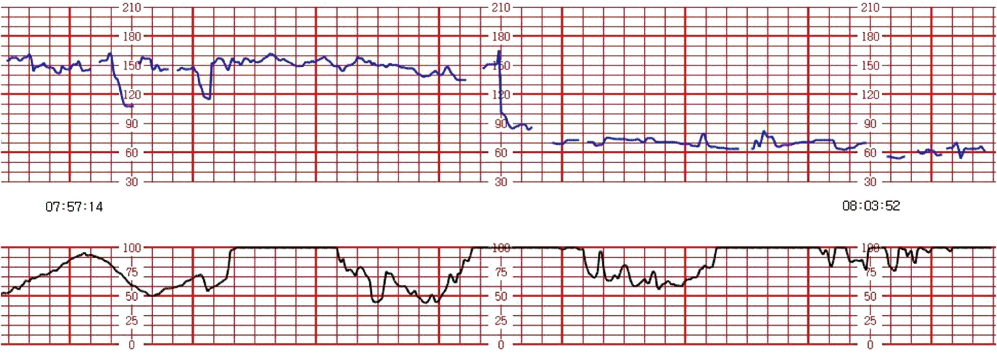

- Umbilical cord prolapse is a rare obstetric emergency that requires an expeditious delivery for fetal survival. This serious obstetrical emergency is unfamiliar to many physicians although it represents an acute emergency with high mortality. We have experienced a woman with umbilical cord prolapse and prolonged fetal heart rate deceleration who underwent an emergent cesarean section under use of propofol and the neonate survived with resuscitation when there were no anesthesiologist and pediatrician. There were no adverse outcomes on the woman and neonate.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Bloom SL, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Gilbert S, Hauth JC, Landon MB, et al. Decision-to-incision times and maternal and infant outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2006. 108:6–11.2. Mesleh R, Sultan M, Sabagh T, Algwiser A. Umbilical cord prolapse. J Obstet Gynecol. 1993. 13:24–28.3. Yla-Outinen A, Heinonen PK, Tuimala R. Predisposing and risk factors of umbilical cord prolapse. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1985. 64:567–570.4. Murphy DJ, MacKenzie IZ. The mortality and morbidity associated with umbilical cord prolapse. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995. 102:826–830.5. Levy H, Meier PR, Makowski EL. Umbilical cord prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 1984. 64:499–502.6. Bock JE, Wiese J. Prolapse of the umbilical cord. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1972. 51:303–308.7. Alouini S, Mesnard L, Megier P, Lemaire B, Coly S, Desroches A. Management of umbilical cord prolapse and neonatal outcomes. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2010. 39:471–477.8. Prabulos AM, Philipson EH. Umbilical cord prolapse. Is the time from diagnosis to delivery critical? J Reprod Med. 1998. 43:129–132.9. Bythell V. Cord prolapse demands general anaesthesia. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2003. 12:287–289.10. Scrutton M. Cord prolapse demands general anaesthesia. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2003. 12:290–292.11. CESDI. Obstetric anaesthesia delays and complications. Confidential Enquiry Into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy, 7th annual report. 2000. London: Maternal and Child Health Research Consortium;41–52.12. MacKenzie IZ, Cooke I. What is a reasonable time from decision-to-delivery by caesarean section? Evidence from 415 deliveries. BJOG. 2002. 109:498–504.13. Wong JM. Propofol infusion syndrome. Am J Ther. 2010. 17:487–491.14. Valtonen M, Kanto J, Rosenberg P. Comparison of propofol and thiopentone for induction of anaesthesia for elective caesarean section. Anaesthesia. 1989. 44:758–762.15. Sanchez-Alcaraz A, Quintana MB, Laguarda M. Placental transfer and neonatal effects of propofol in caesarean section. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1998. 23:19–23.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Effect of Propofol on Neonate in Emergency Cesarean Section

- A comparison of cardiovascular changes of parturient and blood - gas status of newborn umbilical cord blood according to induction agents for Caesarean section

- The Application of Total Intravenous Anesthesia & Propofol-N2O Anesthesia for Cesarean Section

- A Comparison of Propofol-Fentanyl and Propofol-Ketamine Anesthesia for Cesarean Section

- A study for Pertinence in Emergent Cesarean Section