Anat Cell Biol.

2013 Jun;46(2):141-148. 10.5115/acb.2013.46.2.141.

Fetal anatomy of the upper pharyngeal muscles with special reference to the nerve supply: is it an enteric plexus or simply an intramuscular nerve?

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Anatomy, Tokyo Dental College, Chiba, Japan. abesh@tdc.ac.jp

- 2Oral Health Science Center hrc8, Tokyo Dental College, Chiba, Japan.

- 3Division of Otoralyngology, Sendai Municipal Hospital, Sendai, Japan.

- 4Department of Anatomy and Embryology II, School of Medicine, Complutense University, Madrid, Spain.

- 5Division of Internal Medicine, Iwamizawa Kojin-kai Hospital, Iwamizawa, Japan.

- KMID: 2263106

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5115/acb.2013.46.2.141

Abstract

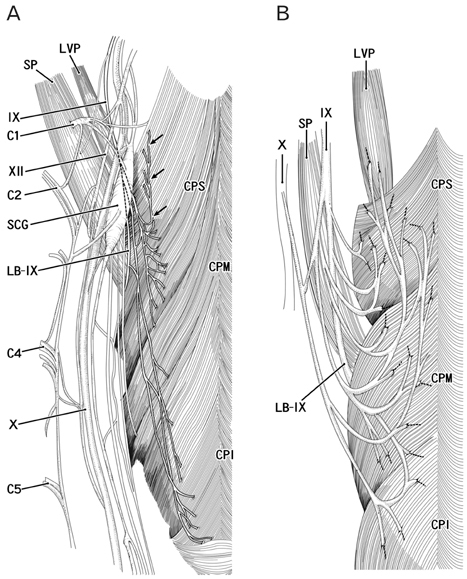

- We examined pharyngeal nerve courses in paraffin-embedded sagittal sections from 10 human fetuses, at 25-35 weeks of gestation, by using S100 protein immunohistochemical analysis. After diverging from the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves at the level of the hyoid bone, the pharyngeal nerves entered the constrictor pharyngis medius muscle, then turned upward and ran superiorly and medially through the constrictor pharyngis superior muscle, to reach either the levator veli palatini muscle or the palatopharyngeus muscle. None of the nerves showed a tendency to run along the posterior surface of the pharyngeal muscles. Therefore, the pharyngeal nerve plexus in adults may become established by exposure of the fetal intramuscular nerves to the posterior aspect of the pharyngeal wall because of muscle degeneration and the subsequent rearrangement of the topographical relationship between the muscles that occurs after birth.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Review of the external carotid plexus: anatomy, function, and clinical manifestations

Shadi E. Razipour, Sina Zarrintan, Mansour Mathkour, Joe Iwanaga, Aaron S. Dumont, R. Shane Tubbs

Anat Cell Biol. 2021;54(2):137-142. doi: 10.5115/acb.20.308.Insertions of the striated muscles in the skin and mucosa: a histological study of fetuses and cadavers

Ji Hyun Kim, Gen Murakami, José Francisco Rodríguez-Vázquez, Ryo Sekiya, Tianyi Yang, Sin-ichi Abe

Anat Cell Biol. 2024;57(2):278-287. doi: 10.5115/acb.24.048.

Reference

-

1. Williams PL. Gray's anatomy. 1995. 38th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.2. Moore KL, Dalley AF, Agur AM. Clinically oriented anatomy. 1999. London: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;959–961.3. Ohtsuka K, Tomita H, Murakami G. Anatomy of the tonsillar bed: topographical relationship between the palatine tonsil and the lingual branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2002. (546):99–109.4. Oda K, Takanashi Y, Katori Y, Fujimiya M, Murakami G, Kawase T. A ganglion cell cluster along the glossopharyngeal nerve near the human palatine tonsil. Acta Otolaryngol. 2013. 133:509–512.5. Rosa AD, Toldt C. Anatomischer atlas: fur Studierende und Ärzte. 1903. Vol. 6. Berlin and Wien: Urban & Schwarzenberg.6. Shimokawa T, Yi SQ, Izumi A, Ru F, Akita K, Sato T, Tanaka S. An anatomical study of the levator veli palatini and superior constrictor with special reference to their nerve supply. Surg Radiol Anat. 2004. 26:100–105.7. Hamilton WJ, Mossman HW. Hamilton, Boyd and Mossmam's human embryology: prenatal development of form and function. 1978. 4th ed. London: Williams & Wilkins;291–335.8. Skandalakis JE, Gray SW. Embryology for surgeons: the embryological basis for the treatment of congenital anomlaies. 1994. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins;17–64.9. O'Rahilly R, Müller F. Human embryology and teratology. 1996. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley-Liss;317–320.10. Doménech-Ratto G. Development and peripheral innervation of the palatal muscles. Acta Anat (Basel). 1977. 97:4–14.11. Abe S, Kikuchi R, Nakao T, Cho BH, Murakami G, Ide Y. Nerve terminal distribution in the human tongue intrinsic muscles: an immunohistochemical study using midterm fetuses. Clin Anat. 2012. 25:189–197.12. Katori Y, Kawase T, Ho Cho K, Abe H, Rodríguez-Vázquez JF, Murakami G, Fujimiya M. Suprahyoid neck fascial configuration, especially in the posterior compartment of the parapharyngeal space: a histological study using late-stage human fetuses. Clin Anat. 2013. 26:204–212.13. Katori Y, Kawase T, Cho KH, Abe H, Rodríguez-Vázquez JF, Murakami G, Abe S. Prestyloid compartment of the parapharyngeal space: a histological study using late-stage human fetuses. Surg Radiol Anat. 2012. 34:909–920.14. Fuse S. An anatomical study of glossopharyngeal nerve. Acta Anat Niigata. 1952. 29:148–188.15. Murakami K, Kuroda M, Kishi K. Variations of the constrictor pharyngeal muscles in humans. Kaibogaku Zasshi. 1996. 71:638–649.16. Futamura R. Über die Entwicklung der facialis muskulatur des Menschen. Anat Hefte. 1906. 30:436–516.17. Podvinec S. The physiology and pathology of the soft palate. J Laryngol Otol. 1952. 66:452–461.18. Ibuki K, Matsuya T, Nishio J, Hamamura Y, Miyazaki T. The course of facial nerve innervation for the levator veli palatini muscle. Cleft Palate J. 1978. 15:209–214.19. Leonhaldt H, Tillman B, Töndury G, Zilles K. Rauber-Kopsch Anatomie des Menschen, Lehrbuch und Atlas, Bd. II Innere Organe. 1987. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The laryngopharyngeal nerve: a comprehensive review

- Bilateral absence of musculocutaneous nerve with unusual branching pattern of lateral cord and median nerve of brachial plexus

- Anatomical variation of median nerve: cadaveric study in brachial plexus

- A rare variation of the glossopharyngeal nerve

- Nerve Repair and Nerve Grafting in Brachial Plexus Injuries