Korean Circ J.

2014 Jul;44(4):210-217. 10.4070/kcj.2014.44.4.210.

Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia in Patients with Post-Infarction Cardiomyopathy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Electrophysiology Section, Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA. egerstenfeld@medicine.ucsf.edu

- KMID: 2223880

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2014.44.4.210

Abstract

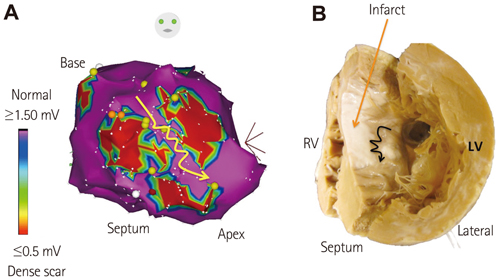

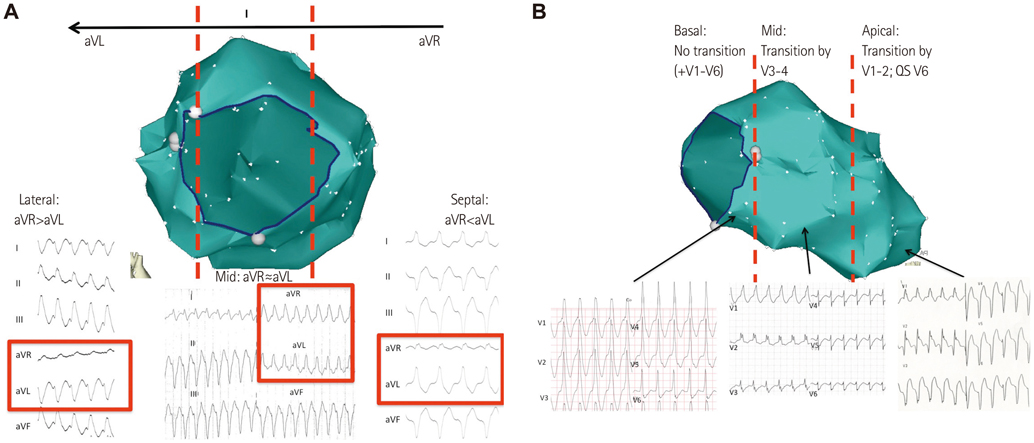

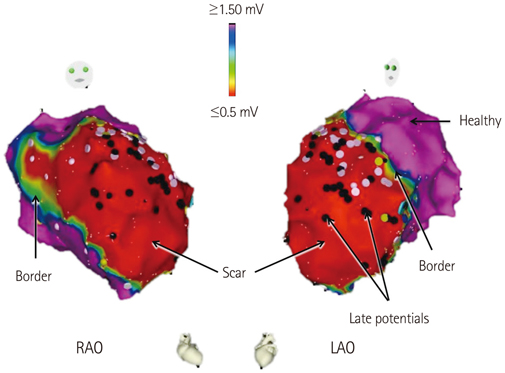

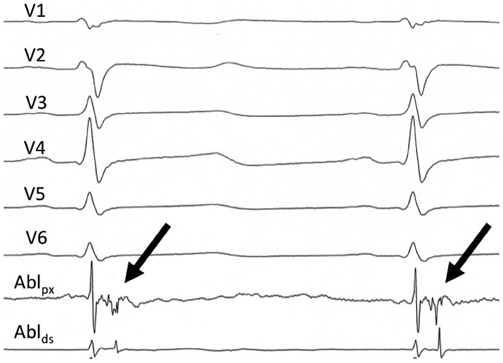

- Monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) in patients with post-infarction cardiomyopathy (CMP) is caused by reentry through slowly conducting tissue with in areas of myocardial scar. The use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) has helped to decrease the risk of arrhythmic death in patients with post-infarction CMP, but the symptomatic and psychological burden of ICD shocks remains significant. Experience with catheter ablation has progressed substantially in the past 20 years, and is now routinely used to treat patients with post-infarction CMP who experience VT or receive ICD therapy. Depending on the hemodynamic tolerance of VT, a variety of mapping techniques may be used to identify sites for catheter ablation, including activation and entrainment mapping for mappable VTs, or substrate mapping for unmappable VTs. In this review, we discuss the pathophysiology of VT in post-infarction CMP patients, and the contemporary practice of catheter ablation.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Mukharji J, Rude RE, Poole WK, et al. Risk factors for sudden death after acute myocardial infarction: two-year follow-up. Am J Cardiol. 1984; 54:31–36.2. Anderson KP, DeCamilla J, Moss AJ. Clinical significance of ventricular tachycardia (3 beats or longer) detected during ambulatory monitoring after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1978; 57:890–897.3. Greenberg H, Case RB, Moss AJ, et al. Analysis of mortality events in the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial (MADIT-II). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004; 43:1459–1465.4. Narang R, Cleland JG, Erhardt L, et al. Mode of death in chronic heart failure. A request and proposition for more accurate classification. Eur Heart J. 1996; 17:1390–1403.5. Buxton AE, Lee KL, Fisher JD, Josephson ME, Prystowsky EN, Hafley G. A randomized study of the prevention of sudden death in patients with coronary artery disease. Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999; 341:1882–1890.6. Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, et al. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352:225–237.7. Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, et al. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:877–883.8. Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, et al. Improved survival with an implanted defibrillator in patients with coronary disease at high risk for ventricular arrhythmia. Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996; 335:1933–1940.9. A comparison of antiarrhythmic-drug therapy with implantable defibrillators in patients resuscitated from near-fatal ventricular arrhythmias. The Antiarrhythmics versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID) Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1997; 337:1576–1583.10. Connolly SJ, Gent M, Roberts RS, et al. Canadian implantable defibrillator study (CIDS) : a randomized trial of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator against amiodarone. Circulation. 2000; 101:1297–1302.11. Kuck KH, Cappato R, Siebels J, Rüppel R. Randomized comparison of antiarrhythmic drug therapy with implantable defibrillators in patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest: the Cardiac Arrest Study Hamburg (CASH). Circulation. 2000; 102:748–754.12. Hegel MT, Griegel LE, Black C, Goulden L, Ozahowski T. Anxiety and depression in patients receiving implanted cardioverter-defibrillators: a longitudinal investigation. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997; 27:57–69.13. Schron EB, Exner DV, Yao Q, et al. Quality of life in the antiarrhythmics versus implantable defibrillators trial: impact of therapy and influence of adverse symptoms and defibrillator shocks. Circulation. 2002; 105:589–594.14. Moss AJ, Greenberg H, Case RB, et al. Long-term clinical course of patients after termination of ventricular tachyarrhythmia by an implanted defibrillator. Circulation. 2004; 110:3760–3765.15. Sweeney MO, Sherfesee L, DeGroot PJ, Wathen MS, Wilkoff BL. Differences in effects of electrical therapy type for ventricular arrhythmias on mortality in implantable cardioverter-defibrillator patients. Heart Rhythm. 2010; 7:353–360.16. Saxon LA, Hayes DL, Gilliam FR, et al. Long-term outcome after ICD and CRT implantation and influence of remote device follow-up: the ALTITUDE survival study. Circulation. 2010; 122:2359–2367.17. Connolly SJ, Dorian P, Roberts RS, et al. Comparison of beta-blockers, amiodarone plus beta-blockers, or sotalol for prevention of shocks from implantable cardioverter defibrillators: the OPTIC Study: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006; 295:165–171.18. Haqqani HM, Kalman JM, Roberts-Thomson KC, et al. Fundamental differences in electrophysiologic and electroanatomic substrate between ischemic cardiomyopathy patients with and without clinical ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 54:166–173.19. Okumura K, Olshansky B, Henthorn RW, Epstein AE, Plumb VJ, Waldo AL. Demonstration of the presence of slow conduction during sustained ventricular tachycardia in man: use of transient entrainment of the tachycardia. Circulation. 1987; 75:369–378.20. de Bakker JM, van Capelle FJ, Janse MJ, et al. Reentry as a cause of ventricular tachycardia in patients with chronic ischemic heart disease: electrophysiologic and anatomic correlation. Circulation. 1988; 77:589–606.21. Morady F, Frank R, Kou WH, et al. Identification and catheter ablation of a zone of slow conduction in the reentrant circuit of ventricular tachycardia in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988; 11:775–782.22. Aliot EM, Stevenson WG, Almendral-Garrote JM, et al. EHRA/HRS Expert Consensus on Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Arrhythmias: developed in a partnership with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), a Registered Branch of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS); in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA). Europace. 2009; 11:771–817.23. Ruffy R, Imran MA, Santel DJ, Wharton JM. Radiofrequency delivery through a cooled catheter tip allows the creation of larger endomyocardial lesions in the ovine heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1995; 6:1089–1096.24. Calkins H, Epstein A, Packer D, et al. Cooled RF Multi Center Investigators Group. Catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in patients with structural heart disease using cooled radiofrequency energy: results of a prospective multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000; 35:1905–1914.25. Tanner H, Hindricks G, Volkmer M, et al. Catheter ablation of recurrent scar-related ventricular tachycardia using electroanatomical mapping and irrigated ablation technology: results of the prospective multicenter Euro-VT-study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010; 21:47–53.26. Stevenson WG, Wilber DJ, Natale A, et al. Irrigated radiofrequency catheter ablation guided by electroanatomic mapping for recurrent ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction: the multicenter thermocool ventricular tachycardia ablation trial. Circulation. 2008; 118:2773–2782.27. Carbucicchio C, Santamaria M, Trevisi N, et al. Catheter ablation for the treatment of electrical storm in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: short- and long-term outcomes in a prospective single-center study. Circulation. 2008; 117:462–469.28. Kuck KH, Schaumann A, Eckardt L, et al. Catheter ablation of stable ventricular tachycardia before defibrillator implantation in patients with coronary heart disease (VTACH): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010; 375:31–40.29. Reddy VY, Reynolds MR, Neuzil P, et al. Prophylactic catheter ablation for the prevention of defibrillator therapy. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357:2657–2665.30. Andersen M, Videbaek R, Boesgaard S, Sander K, Hansen PB, Gustafsson F. Incidence of ventricular arrhythmias in patients on long-term support with a continuous-flow assist device (HeartMate II). J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009; 28:733–735.31. Oz MC, Rose EA, Slater J, Kuiper JJ, Catanese KA, Levin HR. Malignant ventricular arrhythmias are well tolerated in patients receiving long-term left ventricular assist devices. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994; 24:1688–1691.32. Osaki S, Alberte C, Murray MA, et al. Successful radiofrequency ablation therapy for intractable ventricular tachycardia with a ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008; 27:353–356.33. Dandamudi G, Ghumman WS, Das MK, Miller JM. Endocardial catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in patients with ventricular assist devices. Heart Rhythm. 2007; 4:1165–1169.34. Stevenson WG, Khan H, Sager P, et al. Identification of reentry circuit sites during catheter mapping and radiofrequency ablation of ventricular tachycardia late after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1993; 88(4 Pt 1):1647–1670.35. Mountantonakis SE, Park RE, Frankel DS, et al. Relationship between voltage map "channels" and the location of critical isthmus sites in patients with post-infarction cardiomyopathy and ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 61:2088–2095.36. Bogun F, Krishnan S, Siddiqui M, et al. Electrogram characteristics in postinfarction ventricular tachycardia: effect of infarct age. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 46:667–674.37. Bogun F, Good E, Reich S, et al. Isolated potentials during sinus rhythm and pace-mapping within scars as guides for ablation of post-infarction ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 47:2013–2019.38. Hsia HH, Lin D, Sauer WH, Callans DJ, Marchlinski FE. Relationship of late potentials to the ventricular tachycardia circuit defined by entrainment. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2009; 26:21–29.39. Arenal A, Glez-Torrecilla E, Ortiz M, et al. Ablation of electrograms with an isolated, delayed component as treatment of unmappable monomorphic ventricular tachycardias in patients with structural heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003; 41:81–92.40. Jaïs P, Maury P, Khairy P, et al. Elimination of local abnormal ventricular activities: a new end point for substrate modification in patients with scar-related ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2012; 125:2184–2196.41. Di Biase L, Santangeli P, Burkhardt DJ, et al. Endo-epicardial homogenization of the scar versus limited substrate ablation for the treatment of electrical storms in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 60:132–141.42. Frankel DS, Mountantonakis SE, Zado ES, et al. Noninvasive programmed ventricular stimulation early after ventricular tachycardia ablation to predict risk of late recurrence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 59:1529–1535.43. Verma A, Marrouche NF, Schweikert RA, et al. Relationship between successful ablation sites and the scar border zone defined by substrate mapping for ventricular tachycardia post-myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005; 16:465–471.44. Harikrishnan P, Kolte D, Palaniswamy C, et al. Catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia: ten-year trends in utilization, in-hospital complications, and in-hospital mortality in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiology. 2014; 63:12 Suppl 1. A294. Abstract.45. Aryana A, d'Avila A, Heist EK, et al. Remote magnetic navigation to guide endocardial and epicardial catheter mapping of scar-related ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2007; 115:1191–1200.46. Sacher F, Sobieszczyk P, Tedrow U, et al. Transcoronary ethanol ventricular tachycardia ablation in the modern electrophysiology era. Heart Rhythm. 2008; 5:62–68.47. Koruth JS, Dukkipati S, Miller MA, Neuzil P, d'Avila A, Reddy VY. Bipolar irrigated radiofrequency ablation: a therapeutic option for refractory intramural atrial and ventricular tachycardia circuits. Heart Rhythm. 2012; 9:1932–1941.48. Sapp JL, Beeckler C, Pike R, et al. Initial human feasibility of infusion needle catheter ablation for refractory ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2013; 128:2289–2295.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Successful Treatment of Tachycardia-induced Cardiomyopathy with Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation

- Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia/Fibrillation in a Patient with Right Ventricular Amyloidosis with Initial Manifestations Mimicking Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy

- Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Arrhythmias via the Radial Artery in a Patient With Prior Myocardial Infarction and Peripheral Vascular Disease

- Successful Catheter Ablation of Focal Automatic Left Ventricular Tachycardia Presented with Tachycardia-Mediated Cardiomyopathy

- Mid-Septal Hypertrophy and Apical Ballooning; Potential Mechanism of Ventricular Tachycardia Storm in Patients with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy