J Rheum Dis.

2015 Apr;22(2):111-117. 10.4078/jrd.2015.22.2.111.

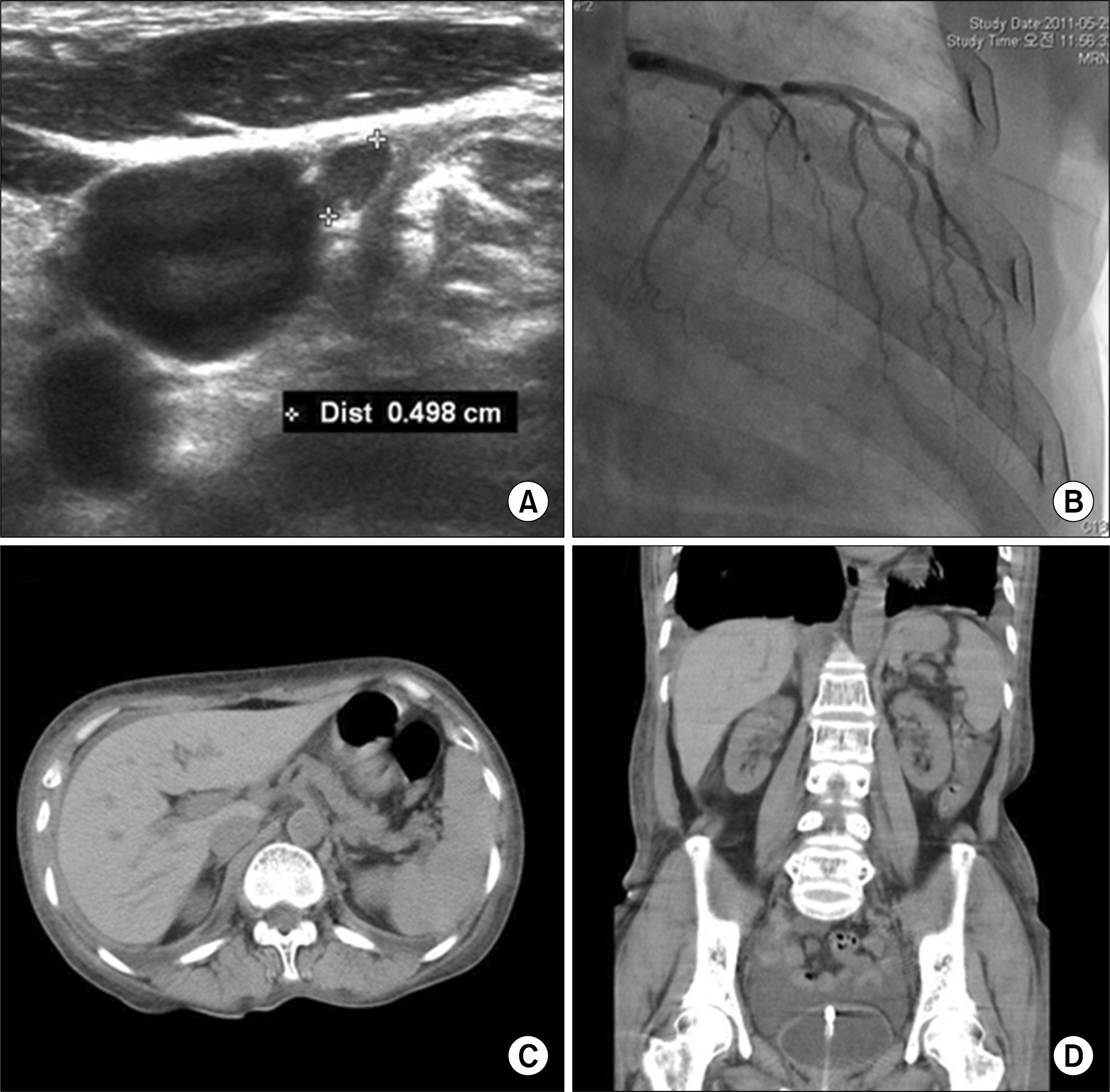

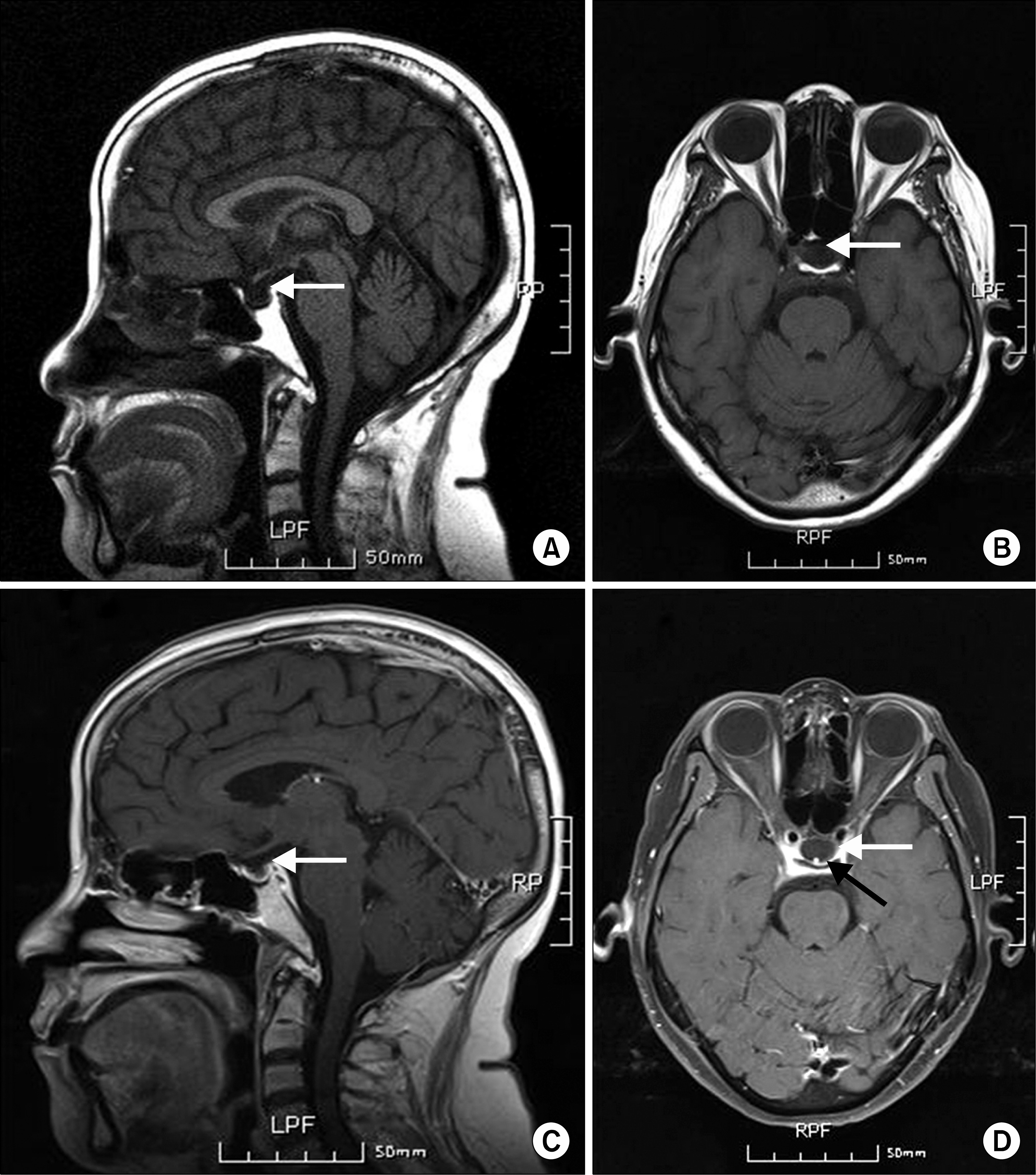

Polyglandular Autoimmune Syndrome Type 2 Complicated by Multiple Organ Failure, Empty Sella Syndrome and Aplastic Anemia

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Yeungnam University College of Medicine, Daegu, Korea. yhhongdr@yahoo.co.kr

- KMID: 2222914

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4078/jrd.2015.22.2.111

Abstract

- Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome (PAS) is a group of syndromes comprised of glandular and extra-glandular disorders characterized by autoimmunity. A 57-year-old woman presented with acute progressive dyspnea and generalized weakness for several months. The patient was assessed to have acute congestive heart failure with cardiomyopathy, chronic renal failure with hyporeninemic hypoaldosteronism, and pancytopenia in addition to primary hypothyroidism and adrenal insufficiency. With the diagnosis of PAS type 2 complicated by multiple organ failure (MOF), medium-dose prednisolone (30 mg/d) was introduced primarily to control the activity of autoimmunity, which triggered MOF over the adrenal insufficiency. Levothyroxine (25 microg/d) was followed for replacement of the thyroid hormone deficiency. However, the symptoms and signs fluctuated, depending on the dosage of prednisolone, and progressively worsened by empty sella syndrome and aplastic anemia. Here, we report on a case of PAS type 2 with MOF and atypical complications, and suggest that recognition, assessment, and control of PAS as a systemic autoimmune disease may be essential.

MeSH Terms

-

Adrenal Insufficiency

Anemia, Aplastic*

Autoimmune Diseases

Autoimmunity

Cardiomyopathies

Diagnosis

Dyspnea

Empty Sella Syndrome*

Female

Heart Failure

Humans

Hypoaldosteronism

Hypothyroidism

Kidney Failure, Chronic

Middle Aged

Multiple Organ Failure*

Pancytopenia

Prednisolone

Thyroid Gland

Thyroxine

Prednisolone

Thyroxine

Figure

Reference

-

1. Michels AW, Gottlieb PA. Autoimmune polyglandular syndromes. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010; 6:270–7.

Article2. Neufeld M, Blizzard RM. Polyglandular autoimmune diseases. Pinchera A, Doniach D, Fenzi GF, Baschieri L, editors. Autoimmune aspects of endocrine disorders. London, UK: Academic Press;1980. p. 357–65.3. Betterle C, Zanchetta R. Update on autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes (APS). Acta Biomed. 2003; 74:9–33.4. Betterle C, Lazzarotto F, Presotto F. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome Type 2: the tip of an iceberg? Clin Exp Immunol. 2004; 137:225–33.

Article5. Chen QY, Kukreja A, Macclaren NK. The autoimmune polyglandular syndromes. de Groot LJ, Jameson JL, editors. Endocrinology. 4th ed.Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders;2001. p. 587–99.6. Betterle C, Dal Pra C, Mantero F, Zanchetta R. Autoimmune adrenal insufficiency and autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes: autoantibodies, autoantigens, and their applicability in diagnosis and disease prediction. Endocr Rev. 2002; 23:327–64.

Article7. Kahaly GJ. Polyglandular autoimmune syndromes. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009; 161:11–20.

Article8. Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM. William's textbook of endocrinology. 12th ed.Massachusetts: Elsevier Saunders;2011. p. 1775–7.9. Dittmar M, Kahaly GJ. Polyglandular autoimmune syndromes: immunogenetics and long-term follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003; 88:2983–92.

Article10. Nielsen TD, Steenbergen C, Russell SD. Nonischemic cardiomyopathy associated with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type II. Endocr Pract. 2007; 13:59–62.

Article11. Schumann C, Faust M, Gerharz M, Ortmann M, Schubert M, Krone W. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome associated with idiopathic giant cell myocarditis. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2005; 113:302–7.

Article12. Hannigan NR, Jabs K, Perez-Atayde AR, Rosen S. Autoimmune interstitial nephritis and hepatitis in polyglandular autoimmune syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 1996; 10:511–4.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Polygrandular Automune type II syndrome associated empty sella

- Two Cases of Graves Disease Associated The Empty Sella Syndrome

- A Case of Empty Sella Syndrome with Cerebrospinal Fluid Rhinorrhea

- A Case of Endoscopic Repair of Cerebrospinal Fluid Rhinorrhea Associated with Primary Empty Sella Syndrome

- A Case of Alopecia Areata Associated with Autoimmune Polyglandular Syndrome Type III