J Korean Acad Prosthodont.

2011 Apr;49(2):152-160. 10.4047/jkap.2011.49.2.152.

Volume difference in upper central incisor preparation according to the changes of restorative design and marginal location

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Prosthodontics, College of Dentistry, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea. kwlee@yuhs.ac

- KMID: 2196122

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4047/jkap.2011.49.2.152

Abstract

- PURPOSE

The aim of this study was to evaluate the volumetric change of teeth after preparation for various designs and margin locations through Micro CT analysis (Skyscan 1076: SKYSCAN, Konitch, Belgium).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

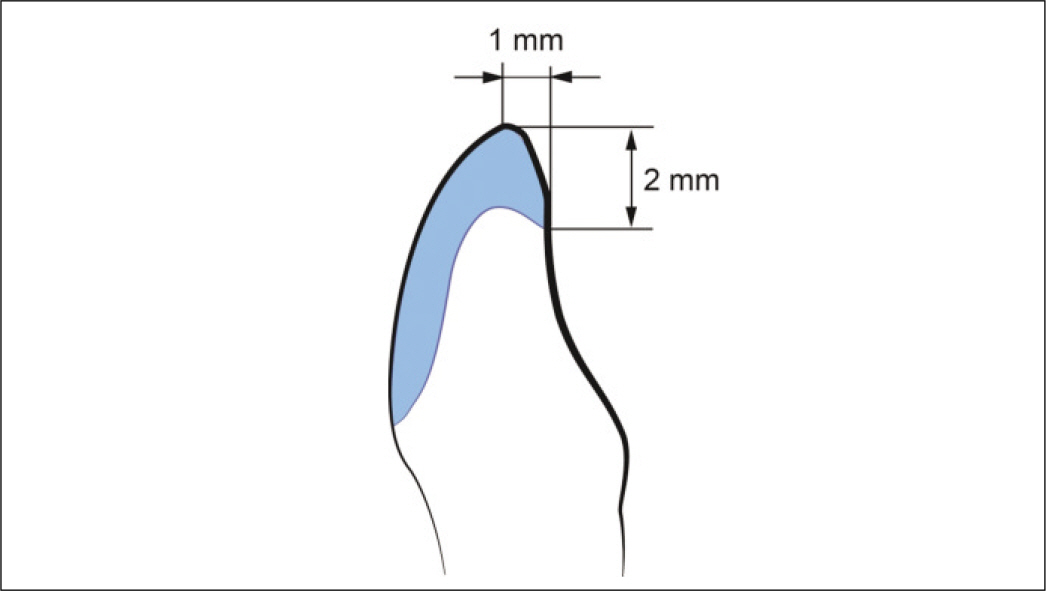

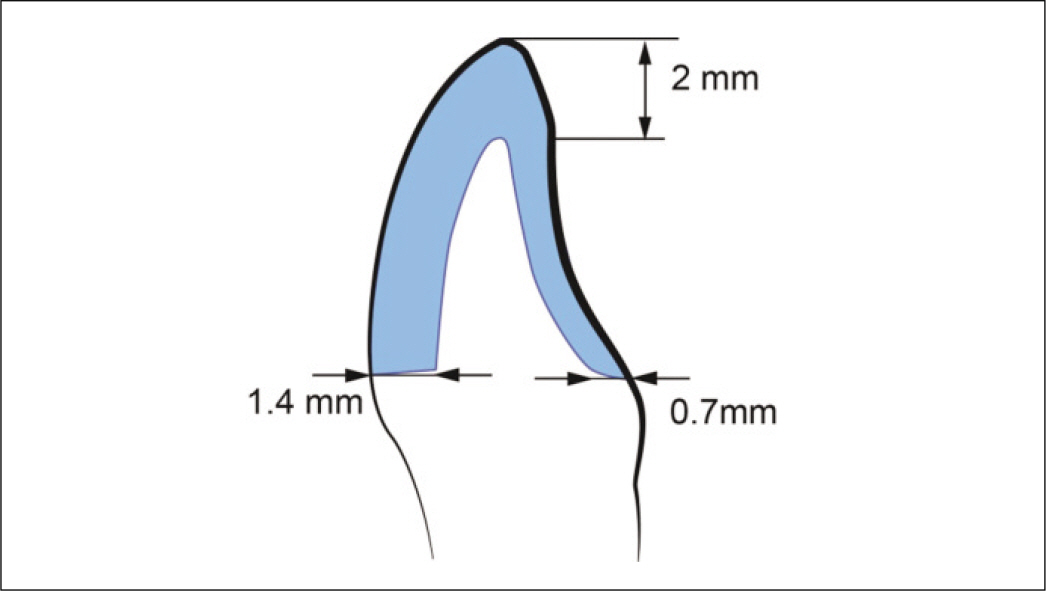

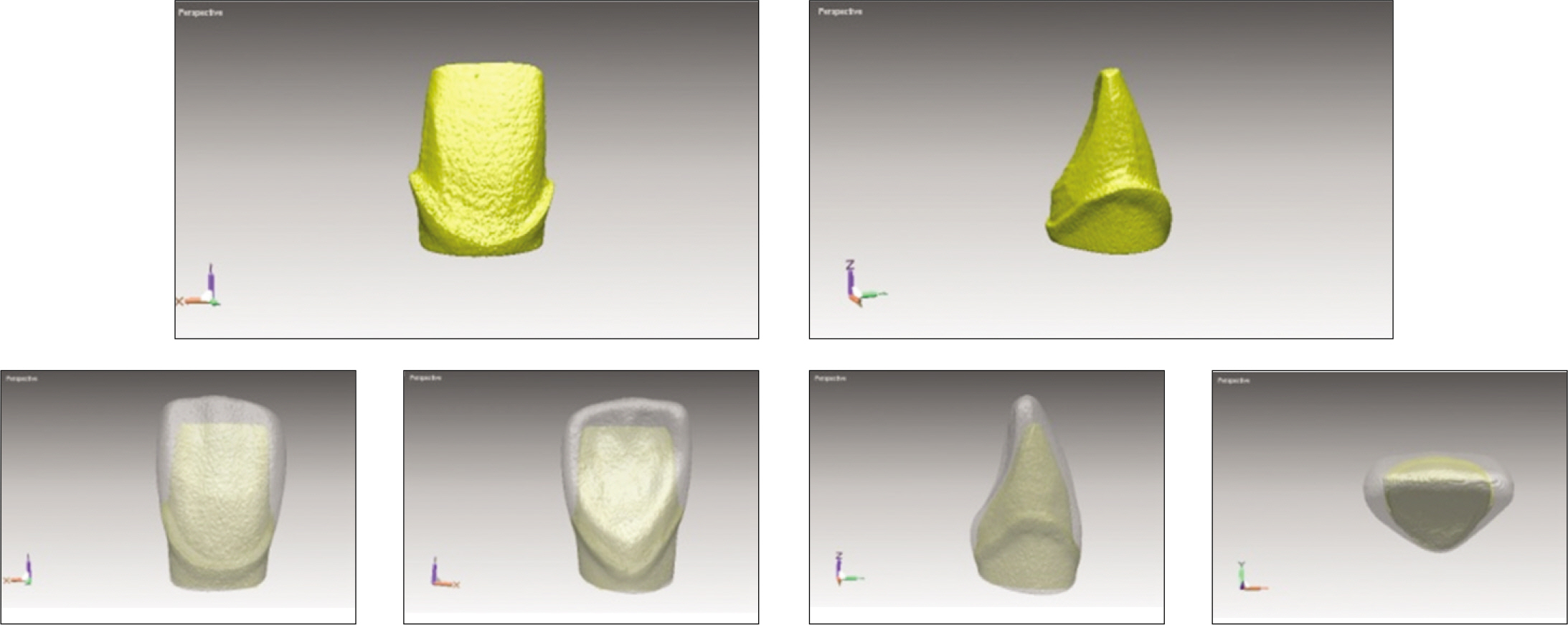

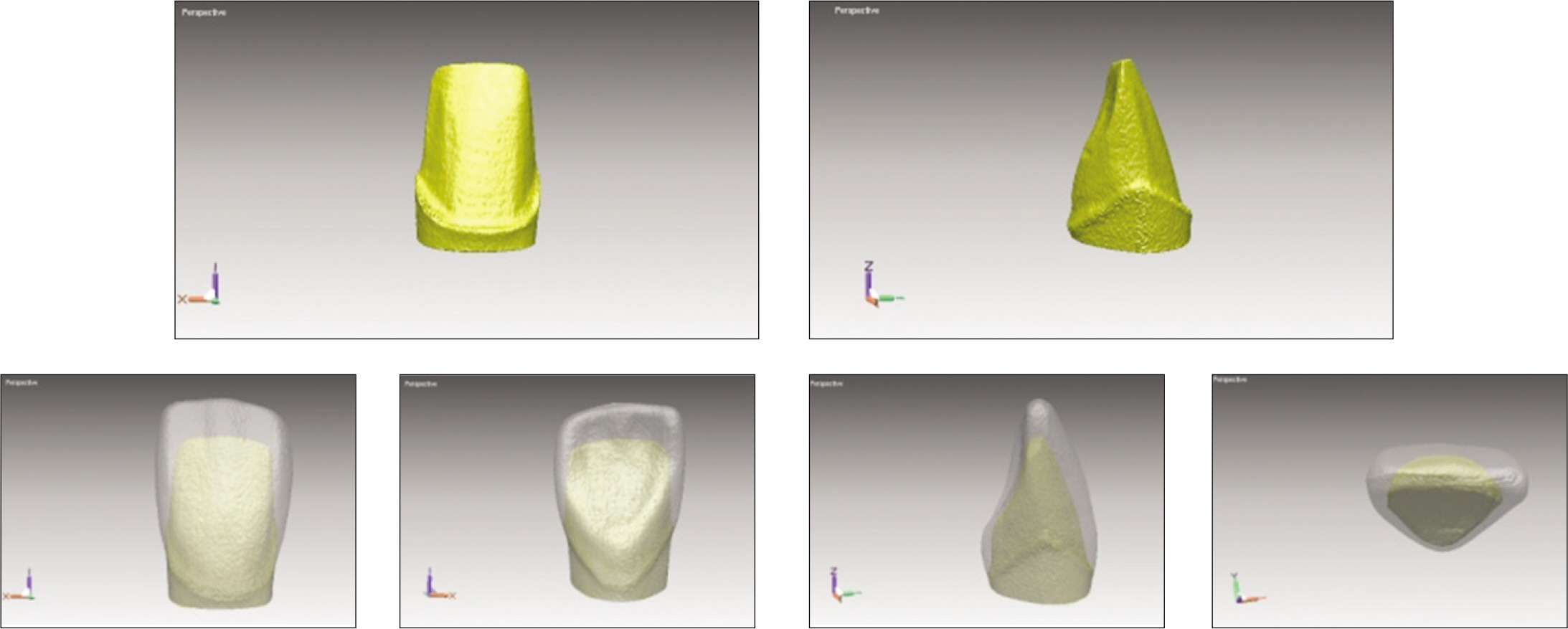

The 36 artificial teeth were used to determine reduction volume of upper central incisor. According to the restorative design these 36 teeth were divided into 4 groups and according to the marginal location each group was divided into 3 subgroups. The volume of unprepared teeth was obtained by using Micro CT and the volume of prepared teeth was obtained in the same method. The CT scanned images before and after preparation were superimposed.

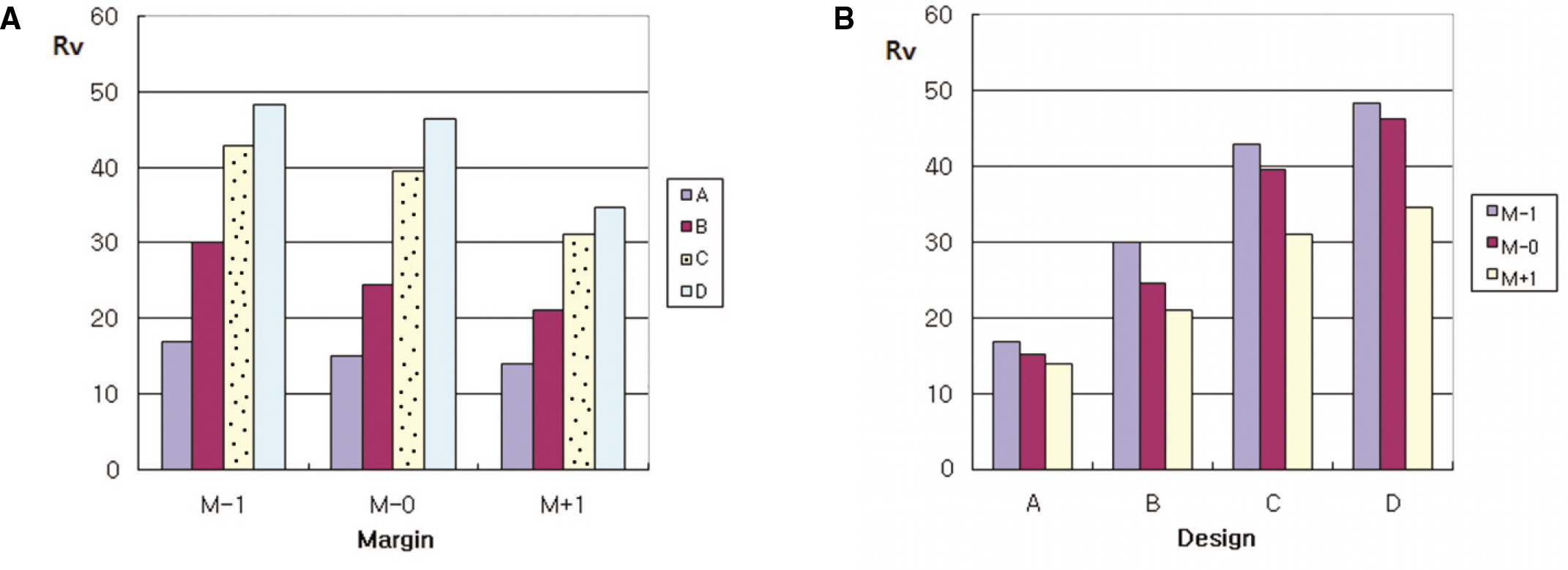

RESULTS

The volume difference was significantly increased as follows: traditional laminate veneer < full laminate veneer < all ceramic crown < metal ceramic crown. One-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparison analyses were used to analyze the data in this study. In each group the volume difference was significantly increased as follows: 1 mm above CEJ < CEJ < 1 mm below CEJ (P<.05). The % volume difference of all ceramic crown and metal ceramic crown was 31 - 48% and that of laminate veneer was 14 - 30%. The volume difference of the traditional laminate veneer was 1/3 of that of metal ceramic crown. The full laminate (1 mm below CEJ) and all ceramic crown (1 mm above CEJ) showed a similar volume difference. Metal ceramic crown showed 13.7 % more volume difference than all ceramic crown.

CONCLUSION

There exists the difference in volumetric change according to designs of restoration and margin locations of preparation.

Figure

Reference

-

1.Edelhoff D., Sorensen JA. Tooth structure removal associated with various preparation designs for anterior teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 2002. 87:503–9.

Article2.Ericson S., Hedega�rd B., Wennstro¨m A. Roentgenographic study of vital abutment teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 1966. 16:981–7.

Article3.Schwartz NL., Whitsett LD., Berry TG., Stewart JL. Unserviceable crowns and fixed partial dentures: life-span and causes for loss of serviceability. J Am Dent Assoc. 1970. 81:1395–401.

Article4.Doyle MG., Goodacre CJ., Munoz CA., Andres CJ. The effect of tooth preparation design on the breaking strength of Dicor crowns: 3. Int J Prosthodont. 1990. 3:327–40.5.Scherrer SS., de Rijk WG. The fracture resistance of all-ceramic crowns on supporting structures with different elastic moduli. Int J Prosthodont. 1993. 6:462–7.6.Lehner C., Studer S., Brodbeck U., Scha¨rer P. Short-term results of IPS-Empress full-porcelain crowns. J Prosthodont. 1997. 6:20–30.

Article7.Sorensen JA., Choi C., Fanuscu MI., Mito WT. IPS Empress crown system: three-year clinical trial results. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1998. 26:130–6.8.Fradeani M., Aquilano A. Clinical experience with Empress crowns. Int J Prosthodont. 1997. 10:241–7.9.Christensen GJ. Has tooth structure been replaced? J Am Dent Assoc. 2002. 133:103–5.

Article10.Clyde JS., Gilmour A. Porcelain veneers: a preliminary review. Br Dent J. 1988. 164:9–14.

Article11.Kress B., Buhl Y., Ha¨hnel S., Eggers G., Sartor K., Schmitter M. Age-and tooth-related pulp cavity signal intensity changes in healthy teeth: a comparative magnetic resonance imaging analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007. 103:134–7.12.Dumfahrt H., Scha¨ffer H. Porcelain laminate veneers. A retrospective evaluation after 1 to 10 years of service: Part II-Clinical results. Int J Prosthodont. 2000. 13:9–18.13.Ferrari M., Patroni S., Balleri P. Measurement of enamel thickness in relation to reduction for etched laminate veneers. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1992. 12:407–13.14.Goodacre CJ., Spolnik KJ. The prosthodontic management of endodontically treated teeth: a literature review. Part I. Success and failure data, treatment concepts. J Prosthodont. 1994. 3:243–50.

Article15.Crispin BJ. Esthetic moieties: enamel thickness. J Esthet Dent. 1993. 5:37.16.Sorensen JA., Munksgaard EC. Relative gap formation adjacent to ceramic inlays with combinations of resin cements and dentin bonding agents. J Prosthet Dent. 1996. 76:472–6.

Article17.Magne P., Douglas WH. Additive contour of porcelain veneers: a key element in enamel preservation, adhesion, and esthetics for aging dentition. J Adhes Dent. 1999. 1:81–92.18.Jones JC. The success rate of anterior crowns. Br Dent J. 1972. 132:399–403.

Article19.Wolf JE., Hakala PE., Kolehmainen L., Ja¨rvinen V. A follow-up study of porcelain and acrylic jacket crowns. Proc Finn Dent Soc. 1978. 74:54–8.20.Foster LV. Failed conventional bridge work from general dental practice: clinical aspects and treatment needs of 142 cases. Br Dent J. 1990. 168:199–201.

Article21.Zarone F., Epifania E., Leone G., Sorrentino R., Ferrari M. Dynamometric assessment of the mechanical resistance of porcelain veneers related to tooth preparation: a comparison between two techniques. J Prosthet Dent. 2006. 95:354–63.

Article22.Stappert CF., Ozden U., Gerds T., Strub JR. Longevity and failure load of ceramic veneers with different preparation designs after exposure to masticatory simulation. J Prosthet Dent. 2005. 94:132–9.

Article23.Guess PC., Stappert CF. Midterm results of a 5-year prospective clinical investigation of extended ceramic veneers. Dent Mater. 2008. 24:804–13.

Article24.Atsu SS., Aka PS., Kucukesmen HC., Kilicarslan MA., Atakan C. Age-related changes in tooth enamel as measured by electron microscopy: implications for porcelain laminate veneers. J Prosthet Dent. 2005. 94:336–41.

Article25.Murray PE., Stanley HR., Matthews JB., Sloan AJ., Smith AJ. Age-related odontometric changes of human teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002. 93:474–82.

Article26.Peumans M., Van Meerbeek B., Lambrechts P., Vuylsteke-Wauters M., Vanherle G. Five-year clinical performance of porcelain veneers. Quintessence Int. 1998. 29:211–21.27.Morse DR. Age-related changes of the dental pulp complex and their relationship to systemic aging. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991. 72:721–45.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Intracrevicular restoration and dentogingival junction(DGJ) Part I : restorative margin and DGJ

- A study on the affecting factors on root resorption

- Comparative analysis of the clinical techniques used in evaluation of marginal accuracy of cast restoration using stereomicroscopy as gold standard

- A study of the crown angulation in normal occlusion

- Marginal accuracy and fracture strength of Targis/Vectris Crowns prepared with different preparation designs