J Korean Acad Oral Health.

2016 Mar;40(1):38-42. 10.11149/jkaoh.2016.40.1.38.

Destabilizing effect of glycyrrhetinic acid on pre-formed biofilms of Streptococcus mutans

- Affiliations

-

- 1LG Household & Health Care Ltd., Daejeon, Korea. shleek@lgcare.com

- KMID: 2190636

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.11149/jkaoh.2016.40.1.38

Abstract

OBJECTIVES

In this study, the destabilizing effect of glycyrrhetinic acid on pre-formed biofilms of Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) was observed.

METHODS

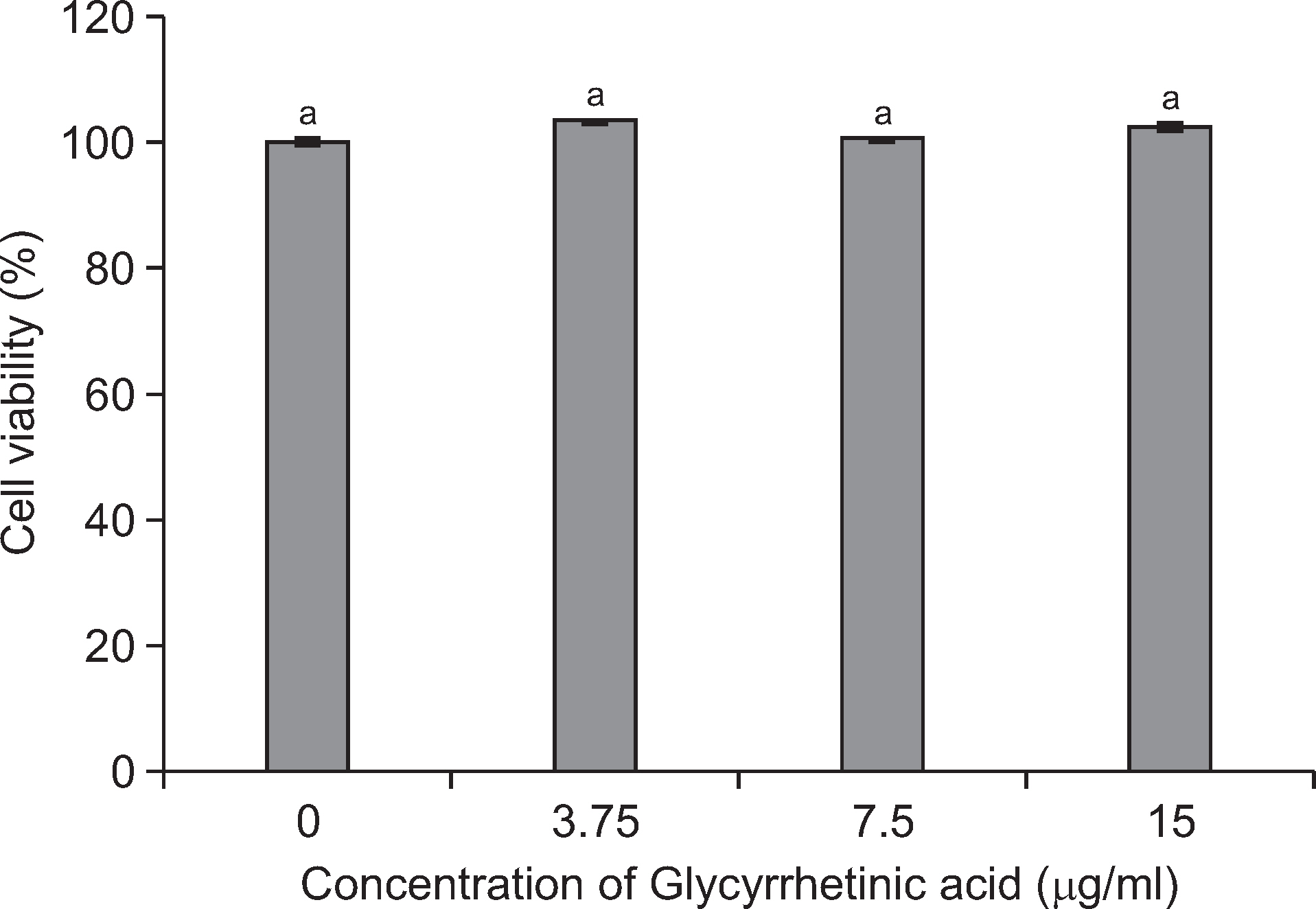

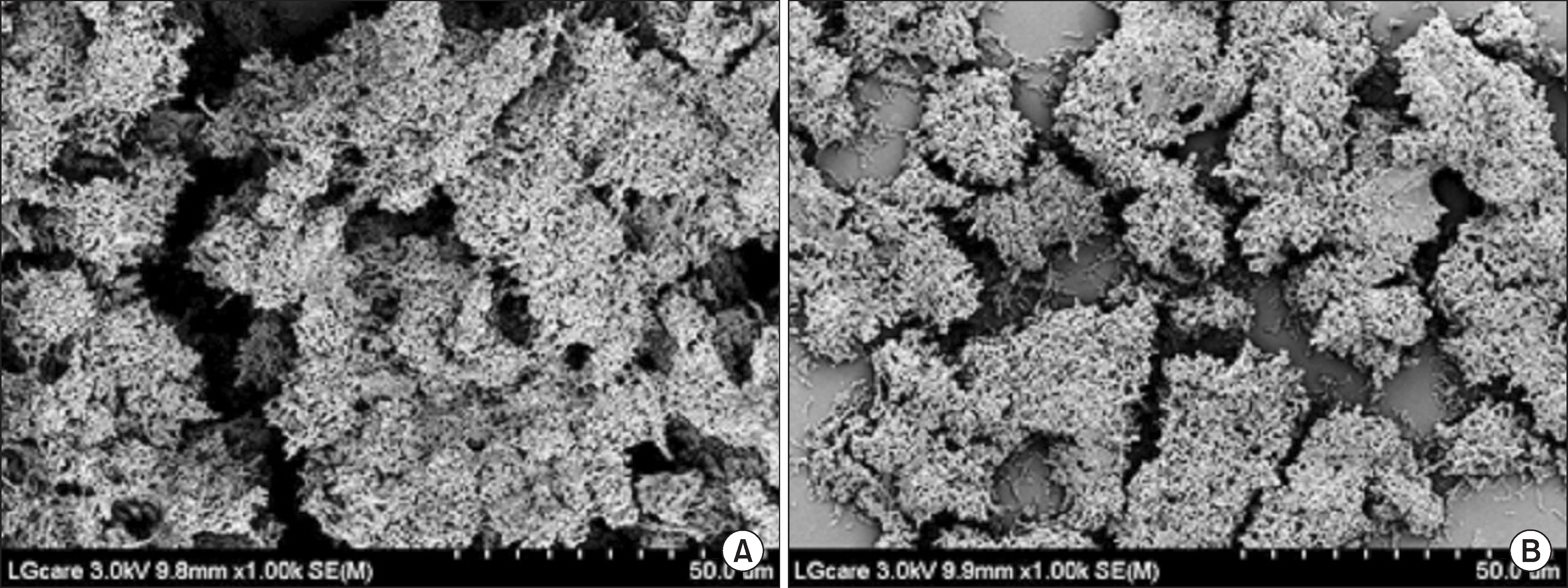

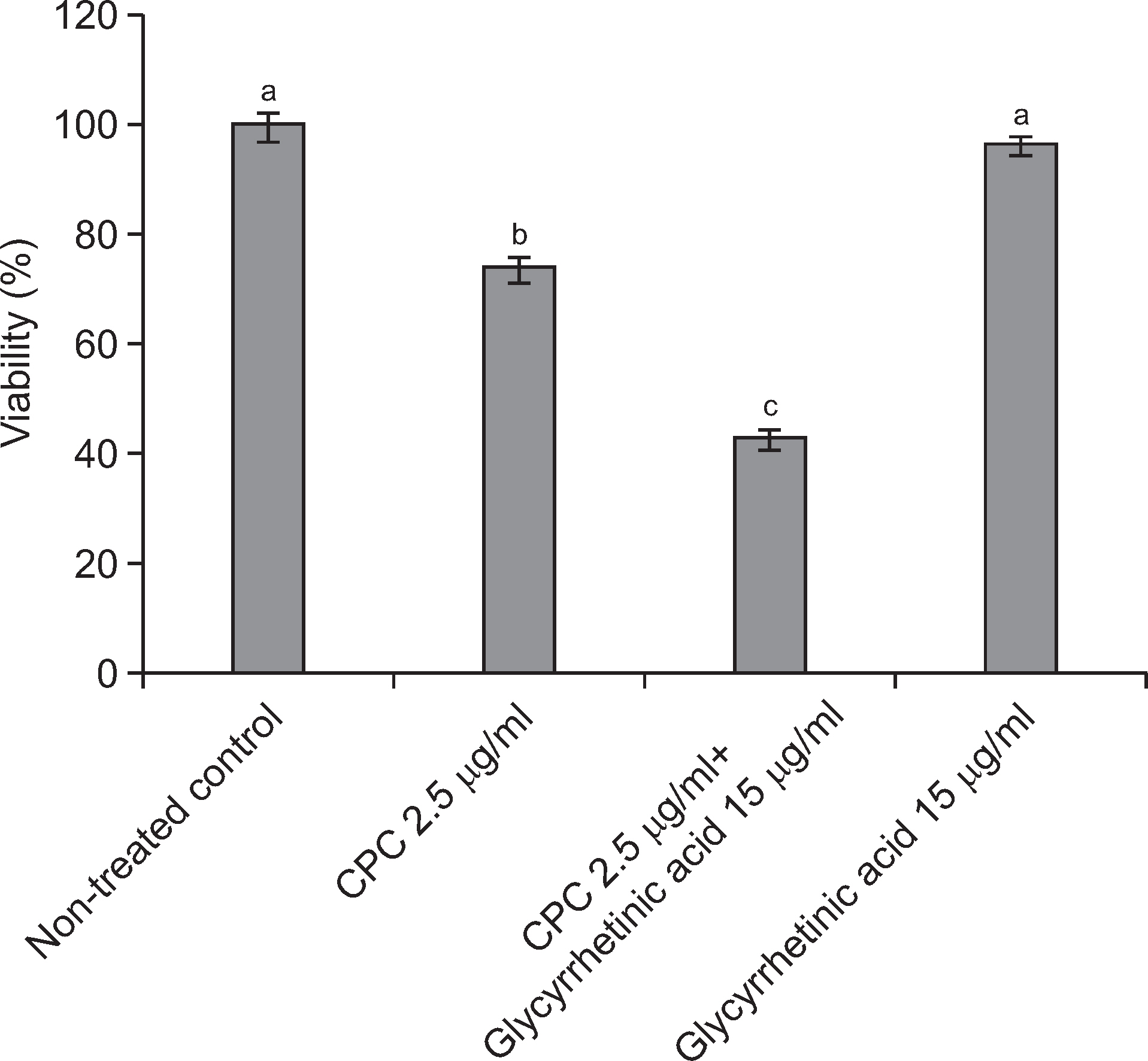

Alamar blue assay was used to determine the toxicity of glycyrrhetinic acid on pre-formed biofilms of S. mutans. Four different concentrations (0, 3.75, 7.5, 15 µg/ml) of glycyrrhetinic acid were tested. Changes in the biofilm architecture after exposure to glycyrrhetinic acid were analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Moreover, the role of glycyrrhetinic acid in enhancing the antimicrobial activity of cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC), an antimicrobial agent commonly used in oral health care products, was evaluated.

RESULTS

Glycyrrhetinic acid concentration of up to 15 µg/ml had little cytotoxic effect but significantly changed the biofilm architecture. SEM analysis revealed destabilized biofilm structure after the preformed biofilms were exposed to glycyrrhetinic acid. Supplementing 2.5 µg/ml CPC with 15 µg/ml glycyrrhetinic acid significantly enhanced the bactericidal effect of CPC on the pre-formed biofilms than that in the non-supplemented CPC treated control. This indicates that glycyrrhetinic acid enhanced the antimicrobial activity of CPC by modifying the structure, thus facilitating the penetration of CPC into the biofilm.

CONCLUSIONS

Glycyrrhetinic acid could be a potential agent to effectively control S. mutans biofilms responsible for dental caries.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Liu Y, Wang L, Zhou X, Hu S, Wu H. Effect of the antimicrobial decapeptide KSL on the growth of oral pathogens and Streptococcus mutans biofilm. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011; 37:33–38.

Article2. Yoshida A, Ansai T, Takehara T, Kuramitsu HK. LuxS-based signaling affects Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation. Appl Environ Microbol. 2005; 71:2372–2380.3. Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: A common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999; 60:756–762.

Article4. Zhiyan H, Qian W, Yuejian H, Jingping L, Yuntao J, Rui M, et al. Use of the quorum sensing inhibitor furanone C-30 to interfere with biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans and its luxS mutant strain. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012; 40:30–35.5. Eley BM. Antibacterial agents in the control of supragingival plaque-a review. Br Dent J. 1999; 186:286–296.6. Loesche WJ. Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol Rev. 1986; 50:353–380.

Article7. Marsh PD. Plaque as a biofilm: pharmacological principles of drug delivery and action in the sub- and supragingival environment. Oral Dis. 2003; 9(Suppl 1):S16–22.

Article8. Pellati D, Fiore C, Armanini D, Rassu M, Bertoloni G. In vitro effects of glycyrrhetinic acid on the growth of clinical isolates of Candida albicans. Phytother Res. 2009; 23:572–574.9. Tsukiyama R, Katsura H, Tokuriki N, Kobayashi M. Antibacterial activity of licochalcone A against spore-forming bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002; 46:1226–1230.

Article10. Asl MN, Hosseinzadeh H. Review of pharmacological effects of Glycyrrhiza sp. and its bioactive compounds. Phytother Res. 2008; 22:709–724.11. Hamid R, Rotshteyn Y, Rabadi L, Parikh R, Bullock P. Comparison of alamar blue and MTT assays for high through-put screening. Toxicol In Vitro. 2004; 18:703–710.

Article12. Robin K. Pettit, Christine A. Weber, Melissa J. Kean, Holger Hoffmann, Geroge R. Pettit, Rui Tan, et al. Microplate alamar blue assay for Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm susceptibility testing. Anti-microb Agents Chemother. 2005; 49:2612–2617.13. Senadheera D, Cvitkovitch DG. Quorum sensing and biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008; 631:178–188.

Article14. Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. Dental biofilms: difficult therapeutic targets. Periodontol 2000. 2002; 28:12–55.

Article15. Park SN, Lim YK, Freire MO, Cho E, Jin D, Kook JK. Antimicrobial effect of linalool and -terpineol against periodontopathic and cariogenic bacteria. Anaerobe. 2012; 18:369–372.

Article16. Paula VA, Modesto A, Santos KR, Gleiser R. Antimicrobial effects of the combination of chlorhexidine and xylitol. Br Dent J. 2010; Oct 1 [Epub]. DOI:10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.887.

Article17. Hassan S, Danishuddin M, Adil M, Singh K, Verma PK, Khan AU. Efficacy of E. officinalis on the cariogenic properties of Streptococcus mutans: a novel and alternative approach to suppress quorum-sensing mechanism. PLoS One. 2012; Jul 5 [Epub]. DOI:10.1371/ journal.pone.0040319.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Inhibitory effect of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid on the biofilm formation of Streptococcus mutans

- Influence of carbonated drinks on acid production in Streptococcus mutans biofilm

- Changes in the composition of artificial cariogenic biofilms over time

- Synergistic effect of xylitol and ursolic acid combination on oral biofilms

- Inhibitory Effect of Continentalic Acid from Aralia continentalis on Streptococcus mutans Biofilm