Anesth Pain Med.

2016 Jan;11(1):28-35. 10.17085/apm.2016.11.1.28.

Analysis of the current state of postoperative patient-controlled analgesia in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Inje University Sanggye Paik Hospital, Seoul, Korea. kyemin@paik.ac.kr

- KMID: 2169066

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.17085/apm.2016.11.1.28

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is a widely used method of postoperative analgesia with the advantage of tailored dosing for each individual. In spite of its popularity, there have been few reports on the current state of PCA in Korea. In this study, the data on PCA management and PCA regimens of medical institutions in Korea were collected and analyzed.

METHODS

Members of the Korean Society for Anesthetic Pharmacology were questioned as to the state of postoperative PCA management, such as acute pain services (APS) and pain assessment. A list of PCA regimens for each institution was also requested and analyzed.

RESULTS

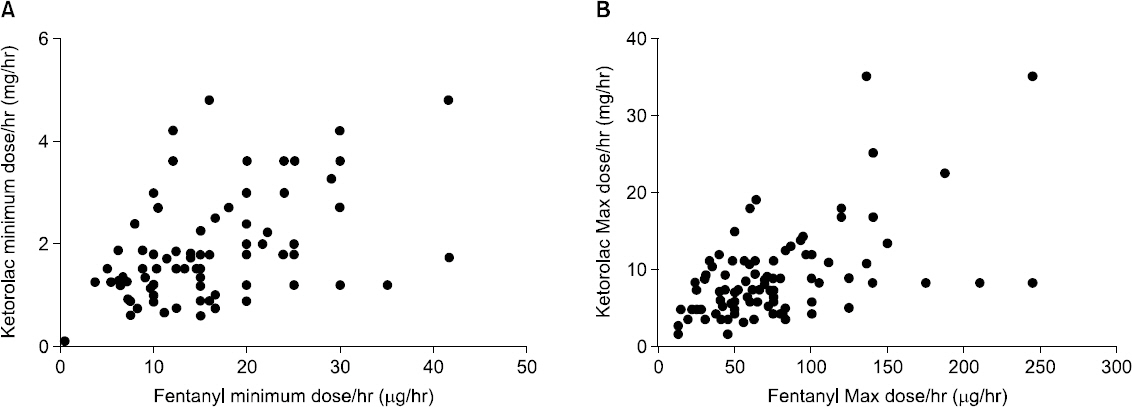

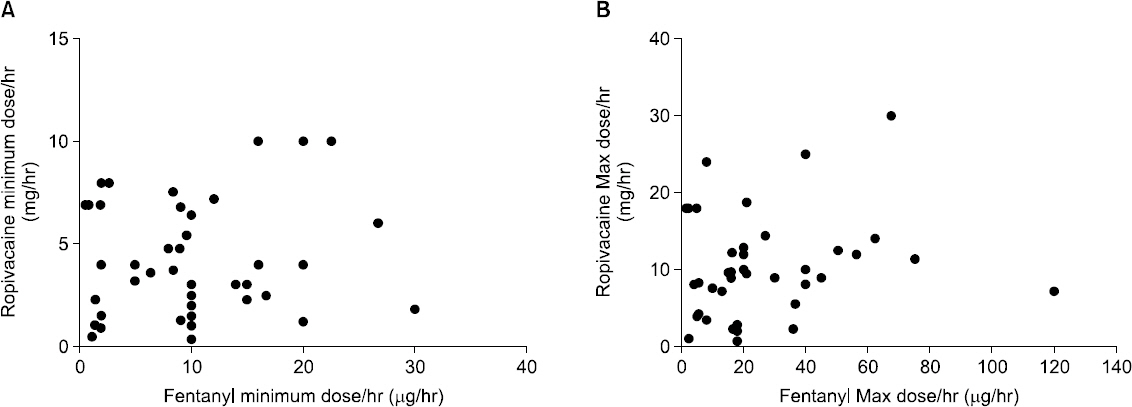

Among 65 hospitals, APS was run in 30 and the severity of postoperative pain was assessed in 60. The safety and efficacy of PCA was evaluated only in 9 hospitals. A total 518 PCA regimens were reported (414, 95 and 9 regimens for intravenous, epidural and other routes, respectively). For intravenous PCA, fentanyl only and fentanyl-ketorolac regimens comprised 33.8 and 30.9% of treatments, respectively. In 95.9% of the regimens, background infusion was used. For epidural PCA, fentanyl-ropivacaine or fentanyl-levobupivacaine regimens made up the majority (47.4 and 13.7%, respectively).

CONCLUSIONS

In Korea, APS was used in less than 50% of the hospitals and the evaluation of the safety and efficacy of PCA is not carried out in the majority. Background infusion, known to have little advantage in most cases, was widely used in intravenous PCA.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Lee GW. A prospective observational cohort study on postoperative intravenous patient-controlled analgesia in surgeries. Anesth Pain Med. 2015; 10:21–6. DOI: 10.17085/apm.2015.10.1.21.

Article2. Kang DH, Kim DS, Kim JD, Kim JW. A comparison of fentanyl and morphine for patient controlled analgesia after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Pain Med. 2013; 8:21–5.3. Etches RC. Respiratory depression associated with patient-controlled analgesia: a review of eight cases. Can J Anaesth. 1994; 41:125–32. DOI: 10.1007/BF03009805. PMID: 8131227.

Article4. Looi-Lyons LC, Chung FF, Chan VW, McQuestion M. Respiratory depression: an adverse outcome during patient controlled analgesia therapy. J Clin Anesth. 1996; 8:151–6. DOI: 10.1016/0952-8180(95)00202-2.

Article5. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute pain Management. Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology. 2012; 116:248–73. DOI: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823c1030. PMID: 22227789.6. Macintyre PE. Safety and efficacy of patient-controlled analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2001; 87:36–46. DOI: 10.1093/bja/87.1.36. PMID: 11460812.

Article7. Werner MU, Søholm L, Rotbøll-Nielsen P, Kehlet H. Does an acute pain service improve postoperative outcome? Anesth Analg. 2002; 95:1361–72. DOI: 10.1097/00000539-200211000-00049. PMID: 12401627.

Article8. Stamer UM, Mpasios N, Stüber F, Maier C. A survey of acute pain services in Germany and a discussion of international survey data. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2002; 27:125–31. DOI: 10.1053/rapm.2002.29258.

Article9. White PF. Multimodal analgesia: its role in preventing postoperative pain. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2008; 9:76–82. PMID: 18183534.10. Camu F, Van Aken H, Bovill JG. Postoperative analgesic effects of three demand-dose sizes of fentanyl administered by patient- controlled analgesia. Anesth Analg. 1998; 87:890–5. DOI: 10.1097/00000539-199810000-00027. PMID: 9768789.11. Hurley RW, Murphy JD, Wu CL. Miller RD, editor. Acute postoperative pain. Miller’s Anesthesia. 2015. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Inc;p. 2974–98.

Article12. Doyle E, Robinson D, Morton NS. Comparison of patient-controlled analgesia with and without a background infusion after lower abdominal surgery in children. Br J Anaesth. 1993; 71:670–3. DOI: 10.1093/bja/71.6.818. PMID: 8251277.

Article13. Owen H, Szekely SM, Plummer JL, Cushnie JM, Mather LE. Variables of patient-controlled analgesia 2. Concurrent infusion. Anaesthesia. 1989; 44:11–3. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1989.tb11088.x. PMID: 2929900.

Article14. Hansen LA, Noyes MA, Lehman ME. Evaluation of patient- controlled analgesia (PCA) versus PCA plus continuous infusion in postoperative cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1991; 6:4–14. DOI: 10.1016/0885-3924(91)90066-D.15. Parker RK, Holtmann B, White PF. Effects of a nighttime opioid infusion with PCA therapy on patient comfort and analgesic requirements after abdominal hysterectomy. Anesthesiology. 1992; 76:362–7. DOI: 10.1097/00000542-199203000-00007. PMID: 1539846.16. George JA, Lin EE, Hanna MN, Murphy JD, Kumar K, Ko PS, et al. The effect of intravenous opioid patient-controlled analgesia with and without background infusion on respiratory depression: a meta-analysis. J Opioid Manag. 2010; 6:47–54. DOI: 10.5055/jom.2010.0004. PMID: 20297614.17. Komatsu H, Matsumoto S, Mitsuhata H. Comparison of patient- controlled epidural analgesia with and without night-time infusion following gastrectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2001; 87:633–5. DOI: 10.1093/bja/87.4.633. PMID: 11878737.18. Macintyre PE, Jarvis DA. Age is the best predictor of postoperative morphine requirements. Pain. 1996; 64:357–64. DOI: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00128-X.

Article19. Kim SH, Hong JY, Kim WO, Kil HK, Karm MH, Hwang JH. Palonosetron has superior prophylactic antiemetic efficacy compared with ondansetron or ramosetron in high-risk patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery: a prospective, randomized, double- blinded study. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013; 64:517–23. DOI: 10.4097/kjae.2013.64.6.517. PMID: 23814652. PMCID: PMC3695249.20. Song SY, Kim HT, Chung JY. Comparison between bolus injection and continuous infusion of ondansetron on nausea and vomiting in intravenous patient-controlled analgesia after laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy using propofol and remifentanil anesthesia. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2008; 54:422–6. DOI: 10.4097/kjae.2008.54.4.422.

Article21. Huh IY, Cheon MY, Choi IC. Comparison of prophylactic antiemetic therapy with patient-controlled epidural analgesia after thoracotomy. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2006; 51:70–5.

Article22. Kim NS, Kang KS, Yoo SH, Chung JH, Chung JW, Seo Y, et al. A comparison of oxycodone and fentanyl in intravenous patient- controlled analgesia after laparoscopic hysterectomy. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2015; 68:261–6. DOI: 10.4097/kjae.2015.68.3.261. PMID: 26045929. PMCID: PMC4452670.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Comparison of Postoperative Analgesia and Side Effects by Patient-Controlled Epidural and Intravenous Analgesia after Cesarean Section

- Postoperative Analgesia

- A national survey of postoperative pain managements in hospitals from the national health insurance database

- Comparison of the Effects of Postoperative Continuous Plus Bolus Patient-Controlled Analgesia and of Bolus Patient-Controlled Analgesia in Children

- Comparison of oxycodone and fentanyl for postoperative patient-controlled analgesia after laparoscopic gynecological surgery