Ewha Med J.

2016 Jan;39(1):6-9. 10.12771/emj.2016.39.1.6.

Hepatic Actinomycosis with Abdominal Wall and Paracolic Gutter Involvement

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Medicine, Sejong General Hospital, Bucheon, Korea. jungok37@gmail.com

- KMID: 2152750

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.12771/emj.2016.39.1.6

Abstract

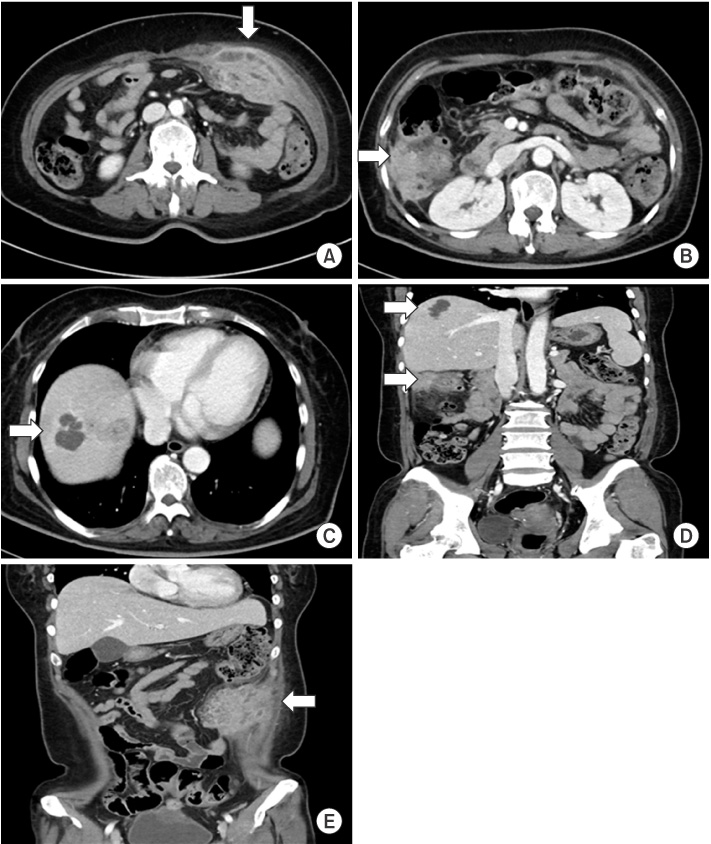

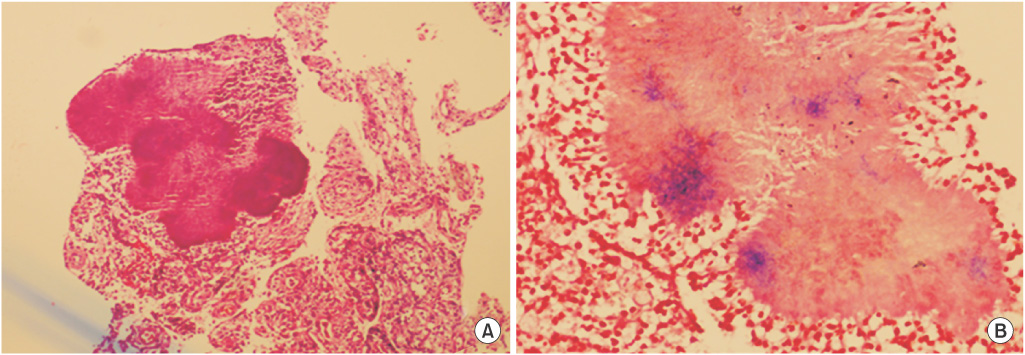

- A 53-year-old female with intrauterine contraceptive device insertion was admitted for painful abdominal mass on the left upper quadrant abdomen. Abdominal computed tomography scan showed multiple enhancing masses on the right lobe of liver, left abdominal wall and right paracolic gutter. We performed incisional biopsy on the left abdominal wall lesion. Although microorganisms were not identified, the histopathologic result was consistent with actinomycosis which contained sulfur granules within the chronic granulomatous inflammation. She was treated with penicillin agents for 6 months. We report a case of hepatic actinomycosis with abdominal wall and paracolic gutter involvement.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases. 8th ed. Philadelphia: PA: Saunders;2014.2. Bennhoff DF. Actinomycosis: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations and a review of 32 cases. Laryngoscope. 1984; 94:1198–1217.3. Yang XX, Lin JM, Xu KJ, Wang SQ, Luo TT, Geng XX, et al. Hepatic actinomycosis: report of one case and analysis of 32 previously reported cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20:16372–16376.4. Brown JR. Human actinomycosis. A study of 181 subjects. Hum Pathol. 1973; 4:319–330.5. Fiorino AS. Intrauterine contraceptive device-associated actinomycotic abscess and Actinomyces detection on cervical smear. Obstet Gynecol. 1996; 87:142–149.6. Kim JU, Park HJ, Song YG, Ji SW, Lee SI, Park CI. A case of primary hepatic actinomycosis coinfected with alpha-streptococcus. Korean J Med. 2002; 63:596–599.7. Wong VK, Turmezei TD, Weston VC. Actinomycosis BMJ. 2011; 343:d6099.8. Lee IJ, Ha HK, Park CM, Kim JK, Kim JH, Kim TK, et al. Abdominopelvic actinomycosis involving the gastrointestinal tract: CT features. Radiology. 2001; 220:76–80.9. Smith AJ, Hall V, Thakker B, Gemmell CG. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Actinomyces species with 12 antimicrobial agents. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005; 56:407–409.10. Fass RJ, Scholand JF, Hodges GR, Saslaw S. Clindamycin in the treatment of serious anaerobic infections. Ann Intern Med. 1973; 78:853–859.