J Cardiovasc Ultrasound.

2011 Mar;19(1):45-49. 10.4250/jcu.2011.19.1.45.

Ovarian Tumor-Associated Carcinoid Heart Disease Presenting as Severe Tricuspid Regurgitation

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center, Daegu, Korea. khyungseop@dsmc.or.kr

- KMID: 2135434

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4250/jcu.2011.19.1.45

Abstract

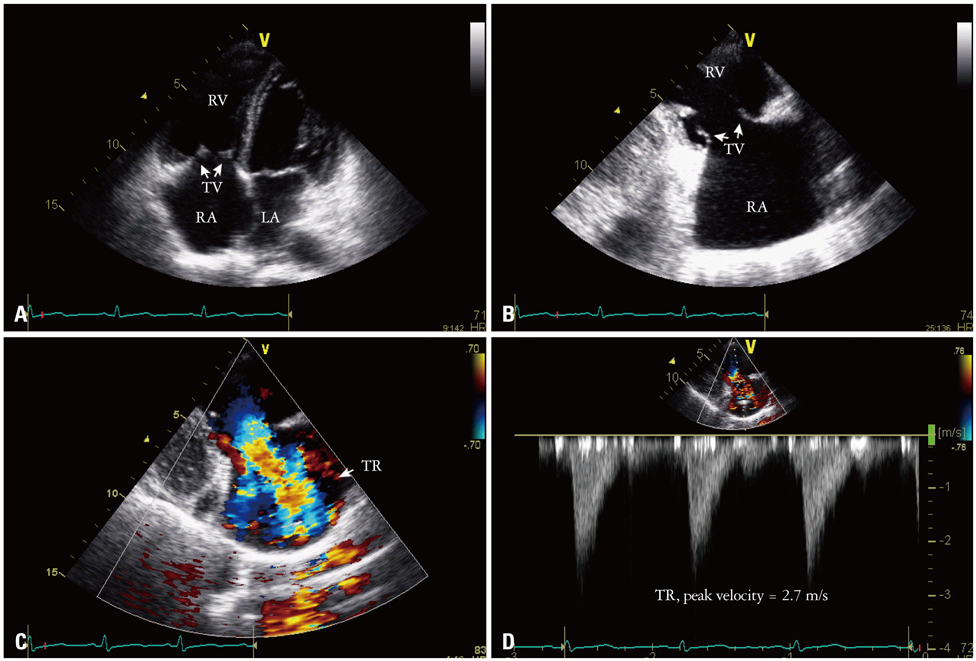

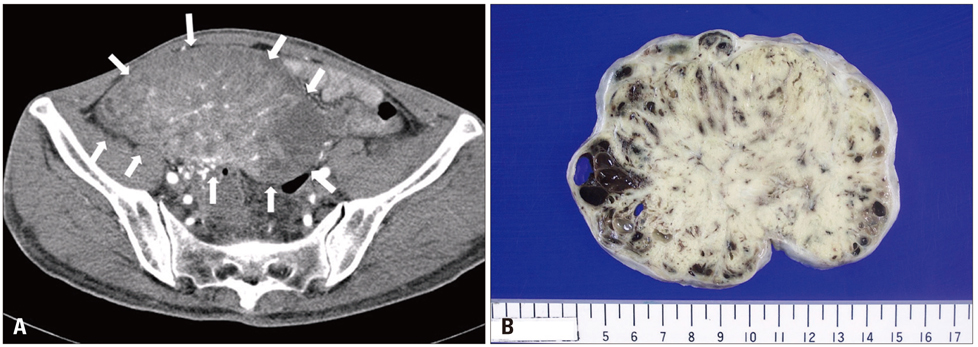

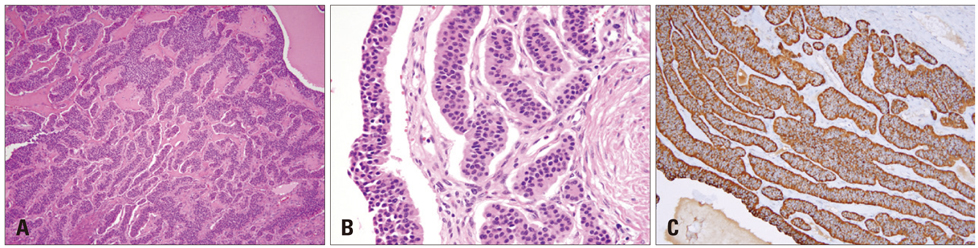

- Carcinoid heart disease is characterized by heart valve dysfunction as well as carcinoid symptomatology. We report a case of carcinoid heart disease associated with a primary ovarian tumor. A 60-year-old woman presented for dyspnea evaluation with a history of facial flushing, telangiectatic skin changes, and pitting edema of both lower extremities. Chest radiography showed cardiomegaly, and echocardiography revealed an isolated, severe tricuspid regurgitation without left-sided valvular dysfunction. The tricuspid leaflets were severely retracted and shortened, resulting in poor coaptation. Furthermore, mild pulmonary valve stenosis and moderate regurgitation were found along with this deformation. The 24-hour urine analysis revealed an increased level of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, and an ovarian tumor was apparent on computed tomography images. The mass was surgically removed, and the patient was diagnosed as having a primary ovarian carcinoid tumor. She was treated with chemotherapy and regularly followed-up with supportive treatments, deferring surgical correction.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Modlin IM, Sandor A. An analysis of 8305 cases of carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 1997. 79:813–829.

Article2. Stephan E, de Wit J. Carcinoid heart disease from primary carcinoid tumour of the ovary. Haemodynamic and cine coronary angiocardiographic study after operation. Br Heart J. 1974. 36:613–616.

Article3. Chaowalit N, Connolly HM, Schaff HV, Webb MJ, Pellikka PA. Carcinoid heart disease associated with primary ovarian carcinoid tumor. Am J Cardiol. 2004. 93:1314–1315.

Article4. Artaza A, Beiner JA, Gonzalez M, Aranda I, de Teresa EG, Pulpon LA. Carcinoid heart disease: report of a case secondary to a pure carcinoid tumour of the ovary. Eur Heart J. 1985. 6:800–805.

Article5. Simula DV, Edwards WD, Tazelaar HD, Connolly HM, Schaff HV. Surgical pathology of carcinoid heart disease: a study of 139 valves from 75 patients spanning 20 years. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002. 77:139–147.

Article6. Blick DR, Zoghbi WA, Lawrie GM, Verani MS. Carcinoid heart disease presenting as right-to-left shunt and congestive heart failure: successful surgical treatment. Am Heart J. 1988. 115:201–203.

Article7. Mansencal N, Mitry E, Forissier JF, Martin F, Redheuil A, Lepére C, Farcot JC, Joseph T, Lacombe P, Rougier P, Dubourg O. Assessment of patent foramen ovale in carcinoid heart disease. Am Heart J. 2006. 151:1129.e1–1129.e6.

Article8. Zuetenhorst JM, Bonfrer JM, Korse CM, Bakker R, van Tinteren H, Taal BG. Carcinoid heart disease: the role of urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid excretion and plasma levels of atrial natriuretic peptide, transforming growth factor-beta and fibroblast growth factor. Cancer. 2003. 97:1609–1615.9. Kim YJ, Sohn DW, Bang YJ, Oh BH, Choi YS, Lee YW. Myocardial Involvement of Carcinoid Heart Disease: A Case Report. J Korean Soc Echocardiogr. 1998. 6:95–99.

Article10. Lundin L, Norheim I, Landelius J, Oberg K, Theodorsson-Norheim E. Carcinoid heart disease: relationship of circulating vasoactive substances to ultrasound-detectable cardiac abnormalities. Circulation. 1988. 77:264–269.

Article11. Møller JE, Connolly HM, Rubin J, Seward JB, Modesto K, Pellikka PA. Factors associated with progression of carcinoid heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2003. 348:1005–1015.

Article12. Møller JE, Pellikka PA, Bernheim AM, Schaff HV, Rubin J, Connolly HM. Prognosis of carcinoid heart disease: analysis of 200 cases over two decades. Circulation. 2005. 112:3320–3327.13. Connolly HM, Pellikka PA. Carcinoid heart disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2006. 8:96–101.

Article14. Pellikka PA, Tajik AJ, Khandheria BK, Seward JB, Callahan JA, Pitot HC, Kvols LK. Carcinoid heart disease. Clinical and echocardiographic spectrum in 74 patients. Circulation. 1993. 87:1188–1196.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Carcinoid Heart Disease: A Rare Cause of Right Ventricular Dysfunction Evaluation by Transthoracic 2D, Doppler and 3-D Echocardiography

- Isolated Tricuspid Regurgitation Caused by Annular Dilatation

- Improvement of Severe Tricuspid Regurgitation with Right Heart Failure Associated with Thyrotoxicosis due to Graves' Disease

- Reversible severe tricuspid regurgitation with right heart failure associated with thyrotoxicosis

- Tricuspid Regurgitation in Heart Diseases in Infants and Children