J Cardiovasc Ultrasound.

2011 Mar;19(1):21-25. 10.4250/jcu.2011.19.1.21.

Endothelial Dysfunction in the Smokers Can Be Improved with Oral Cilostazol Treatment

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Chungnam National University, Chungnam National University Hospital, Daejeon Cardiocerebrovascular Center, Daejeon, Korea. jaehpark@cnuh.co.kr

- KMID: 2135428

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4250/jcu.2011.19.1.21

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Smoking is one of well known environmental factors causing endothelial dysfunction and plays important role in the atherosclerosis. We investigated the effect of cilostazol could improve the endothelial dysfunction in smokers with the measurement of flow-mediated dilatation (FMD).

METHODS

We enrolled 10 normal healthy male persons and 20 male smokers without any known cardiovascular diseases. After measurement of baseline FMD, the participants were medicated with oral cilostazol 100 mg bid for two weeks. We checked the follow up FMD after two weeks and compared these values between two groups.

RESULTS

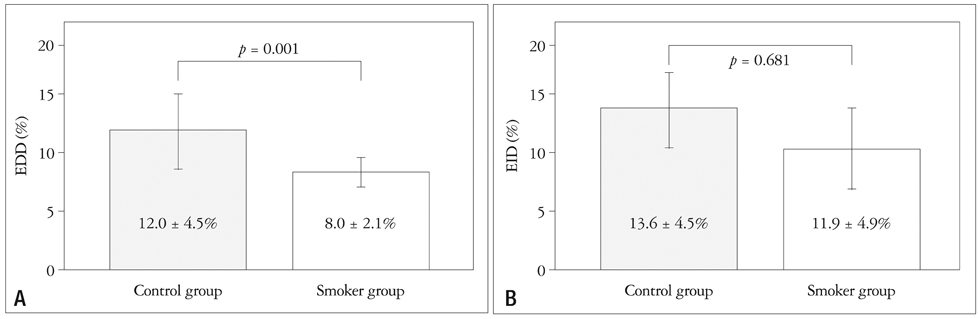

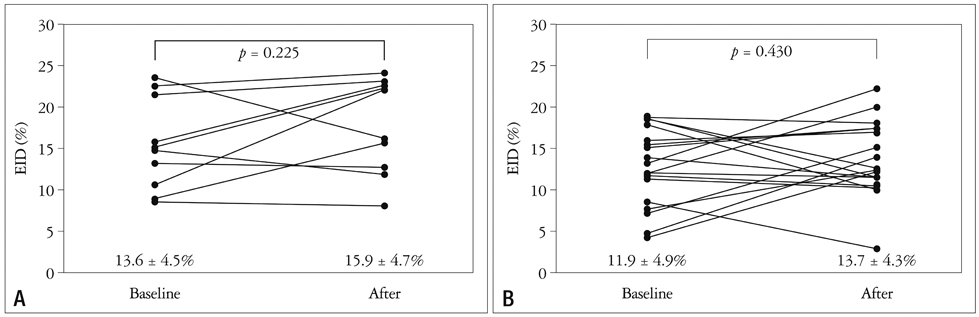

There was no statistical difference of baseline characteristics including age, body mass index, serum cholesterol profiles, serum glucose and high sensitive C-reactive protein between two groups. However, the control group showed significantly higher baseline endothelium-dependent dilatation (EDD) after reactive hyperemia (12.0 +/- 4.5% in the control group vs. 8.0 +/- 2.1% in the smoker group, p = 0.001). However, endothelium-independent dilatation (EID) after sublingual administration of nitroglycerin was similar between the two groups (13.6 +/- 4.5% in the control group vs. 11.9 +/- 4.9% in the smoker group, p = 0.681). Two of the smoker group were dropped out due to severe headache. After two weeks of cilostazol therapy, follow-up EDD were significantly increased in two groups (12.0 +/- 4.5% to 16.1 +/- 3.7%, p = 0.034 in the control group and 8.0 +/- 2.1% to 12.2 +/- 5.1%, p = 0.003 in the smoker group, respectively). However, follow up EID value was not significantly increased compared with baseline value in both groups (13.6 +/- 4.5% to 16.1 +/- 3.7%, p = 0.182 in the control group and 11.9 +/- 4.9% to 13.7 +/- 4.3%, p = 0.430 in the smoker group, respectively).

CONCLUSION

Oral cilostazol treatment significantly increased the vasodilatory response to reactive hyperemia in two groups. It can be used to improve endothelial function in the patients with endothelial dysfunction caused by cigarette smoking.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Celermajer DS. Endothelial dysfunction: does it matter? Is it reversible? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997. 30:325–333.

Article2. Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993. 362:801–809.

Article3. Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Gooch VM, Spiegelhalter DJ, Miller OI, Sullivan ID, Lloyd JK, Deanfield JE. Non-invasive detection of endothelial dysfunction in children and adults at risk of atherosclerosis. Lancet. 1992. 340:1111–1115.

Article4. Jeong YH, Lee SW, Choi BR, Kim IS, Seo MK, Kwak CH, Hwang JY, Park SW. Randomized comparison of adjunctive cilostazol versus high maintenance dose clopidogrel in patients with high post-treatment platelet reactivity: results of the ACCEL-RESISTANCE (Adjunctive Cilostazol Versus High Maintenance Dose Clopidogrel in Patients With Clopidogrel Resistance) randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009. 53:1101–1109.

Article5. Kelm M. Flow-mediated dilatation in human circulation: diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002. 282:H1–H5.6. Joannides R, Haefeli WE, Linder L, Richard V, Bakkali EH, Thuillez C, Luscher TF. Nitric oxide is responsible for flow-dependent dilatation of human peripheral conduit arteries in vivo. Circulation. 1995. 91:1314–1319.

Article7. Wang T, Elam MB, Forbes WP, Zhong J, Nakajima K. Reduction of remnant lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations by cilostazol in patients with intermittent claudication. Atherosclerosis. 2003. 171:337–342.

Article8. Dawson DL, Cutler BS, Meissner MH, Strandness DE Jr. Cilostazol has beneficial effects in treatment of intermittent claudication: results from a multicenter, randomized, prospective, double-blind trial. Circulation. 1998. 98:678–686.

Article9. Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986. 1:307–310.

Article10. Cooke JP, Tsao PS. Is NO an endogenous antiatherogenic molecule? Arterioscler Thromb. 1994. 14:653–655.

Article11. Vogel RA, Corretti MC, Plotnick GD. Effect of a single high-fat meal on endothelial function in healthy subjects. Am J Cardiol. 1997. 79:350–354.

Article12. Ghiadoni L, Donald AE, Cropley M, Mullen MJ, Oakley G, Taylor M, O'Connor G, Betteridge J, Klein N, Steptoe A, Deanfield JE. Mental stress induces transient endothelial dysfunction in humans. Circulation. 2000. 102:2473–2478.

Article13. Lekakis J, Papamichael C, Vemmos C, Nanas J, Kontoyannis D, Stamatelopoulos S, Moulopoulos S. Effect of acute cigarette smoking on endothelium-dependent brachial artery dilatation in healthy individuals. Am J Cardiol. 1997. 79:529–531.

Article14. Kawano H, Motoyama T, Hirashima O, Hirai N, Miyao Y, Sakamoto T, Kugiyama K, Ogawa H, Yasue H. Hyperglycemia rapidly suppresses flow-mediated endothelium-dependent vasodilation of brachial artery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999. 34:146–154.

Article15. Bevan JA. Flow regulation of vascular tone. Its sensitivity to changes in sodium and calcium. Hypertension. 1993. 22:273–281.

Article16. Mombouli JV, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelial dysfunction: from physiology to therapy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999. 31:61–74.

Article17. Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, Carnethon M, Dai S, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Ford E, Furie K, Gillespie C, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho PM, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lackland D, Lisabeth L, Marelli A, McDermott MM, Meigs J, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino M, Nichol G, Roger VL, Rosamond W, Sacco R, Sorlie P, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wong ND, Wylie-Rosett J. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010. 121:e46–e215.18. Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004. 328:1519.

Article19. Ambrose JA, Barua RS. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: an update. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004. 43:1731–1737.20. Benowitz NL. Cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology and implications for treatment. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2003. 46:91–111.

Article21. Hill JM, Zalos G, Halcox JP, Schenke WH, Waclawiw MA, Quyyumi AA, Finkel T. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells, vascular function, and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2003. 348:593–600.

Article22. Hadi HA, Carr CS, Al Suwaidi J. Endothelial dysfunction: cardiovascular risk factors, therapy, and outcome. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2005. 1:183–198.23. Johnson HM, Gossett LK, Piper ME, Aeschlimann SE, Korcarz CE, Baker TB, Fiore MC, Stein JH. Effects of smoking and smoking cessation on endothelial function: 1-year outcomes from a randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010. 55:1988–1995.24. Guthikonda S, Sinkey C, Barenz T, Haynes WG. Xanthine oxidase inhibition reverses endothelial dysfunction in heavy smokers. Circulation. 2003. 107:416–421.

Article25. Oida K, Ebata K, Kanehara H, Suzuki J, Miyamori I. Effect of cilostazol on impaired vasodilatory response of the brachial artery to ischemia in smokers. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2003. 10:93–98.

Article26. Yasuda K, Sakuma M, Tanabe T. Hemodynamic effect of cilostazol on increasing peripheral blood flow in arteriosclerosis obliterans. Arzneimittelforschung. 1985. 35:1198–1200.27. Hiatt WR. Medical treatment of peripheral arterial disease and claudication. N Engl J Med. 2001. 344:1608–1621.

Article28. Lee SW, Park SW, Kim YH, Yun SC, Park DW, Lee CW, Hong MK, Kim HS, Ko JK, Park JH, Lee JH, Choi SW, Seong IW, Cho YH, Lee NH, Kim JH, Chun KJ, Park SJ. Drug-eluting stenting followed by cilostazol treatment reduces late restenosis in patients with diabetes mellitus the DECLARE-DIABETES Trial (A Randomized Comparison of Triple Antiplatelet Therapy with Dual Antiplatelet Therapy After Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation in Diabetic Patients). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008. 51:1181–1187.

Article29. Ikeda U, Ikeda M, Kano S, Kanbe T, Shimada K. Effect of cilostazol, a cAMP phosphodiesterase inhibitor, on nitric oxide production by vascular smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996. 314:197–202.

Article30. Nakamura T, Houchi H, Minami A, Sakamoto S, Tsuchiya K, Niwa Y, Minakuchi K, Nakaya Y. Endothelium-dependent relaxation by cilostazol, a phosphodiesteras III inhibitor, on rat thoracic aorta. Life Sci. 2001. 69:1709–1715.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- HO-1 Induced by Cilostazol Protects Against TNF-alpha-associated Cytotoxicity via a PPAR-gamma-dependent Pathway in Human Endothelial Cells

- Synergistic Efficacy of Concurrent Treatment with Cilostazol and Probucol on the Suppression of Reactive Oxygen Species and Inflammatory Markers in Cultured Human Coronary Artery Endothelial Cells

- The Effect of Green Tea on Endothelial Function and the Circulating Endothelial Progenitor Cell in Chronic Smokers

- Clinical Effect of Cilostazol in Diabetic Patients with Peripheral Vascular Disease

- Better Chemotherapeutic Response of Small Cell Lung Cancer in Never Smokers than in Smokers