J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2008 Feb;49(2):205-212. 10.3341/jkos.2008.49.2.205.

Pterygium Surgery: Wide Excision with Conjunctivo-Limbal Autograft

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Daegu Fatima Hospital, Daegu, Korea. djoph2540@yahoo.co.kr

- KMID: 2127110

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2008.49.2.205

Abstract

-

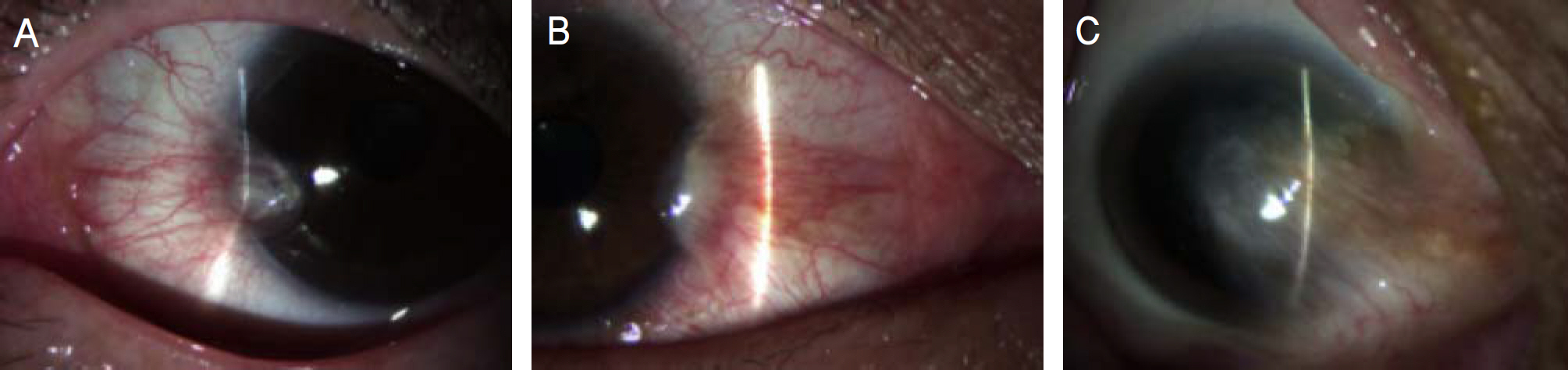

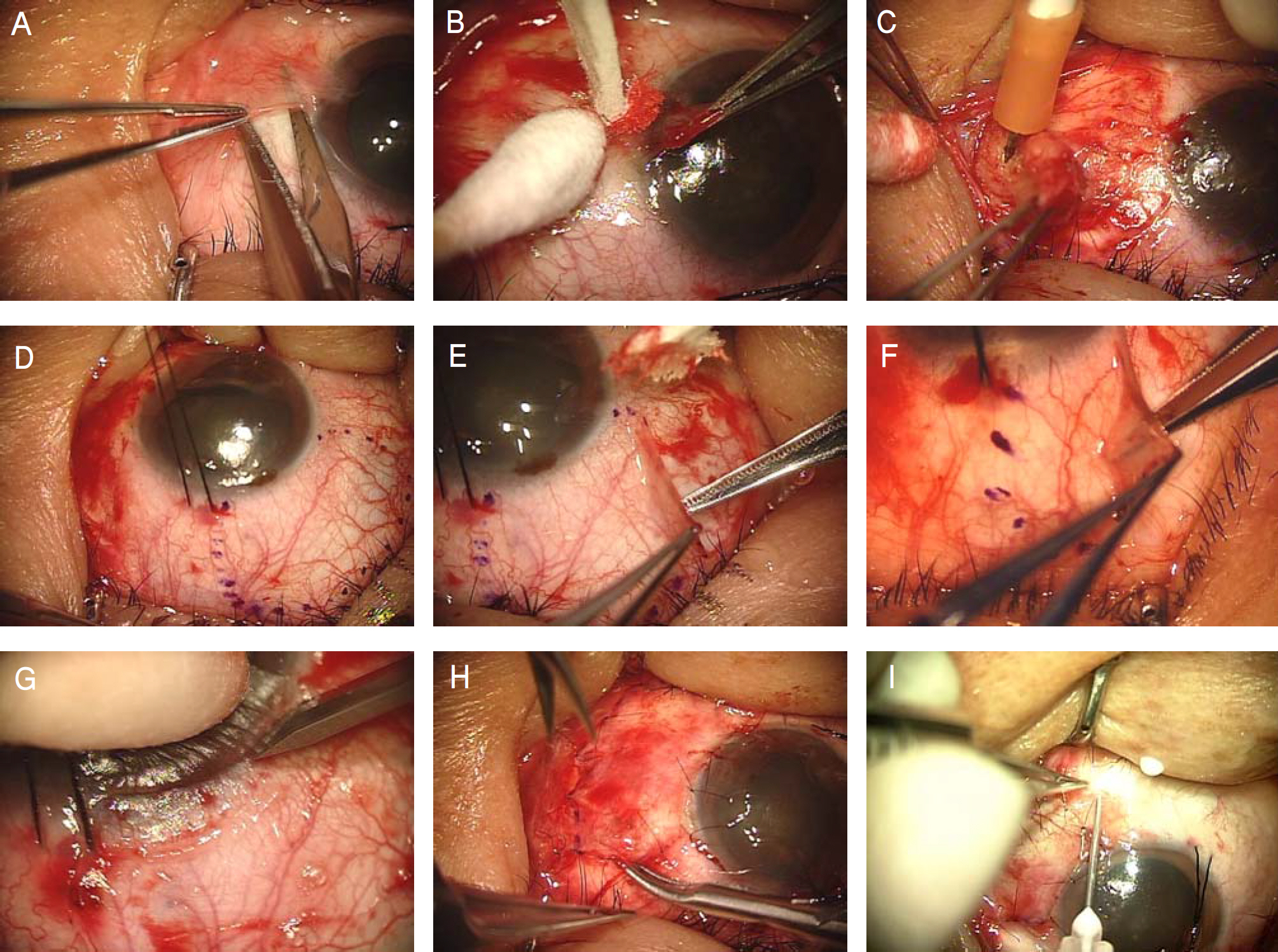

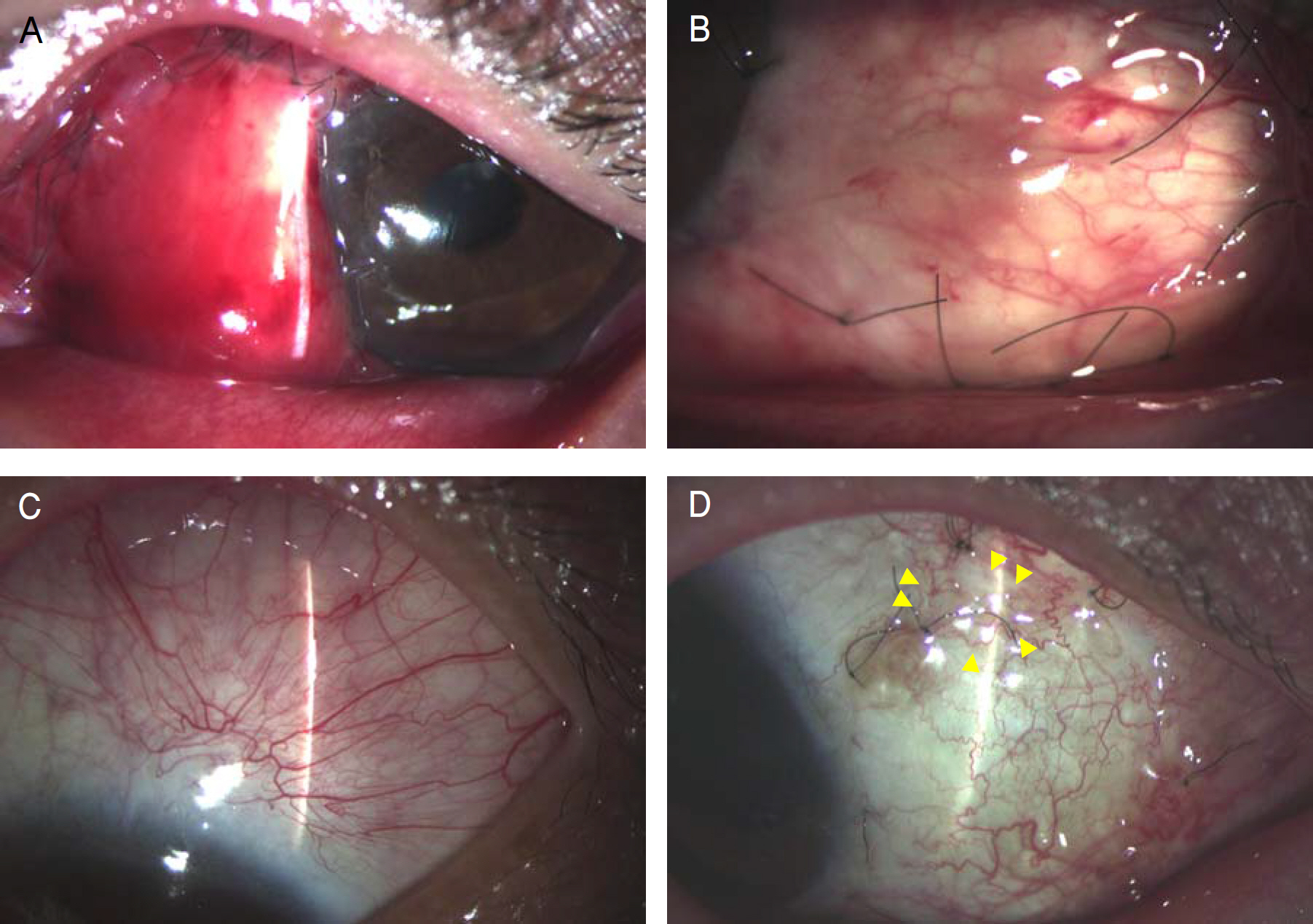

PURPOSE: To evaluate the efficacy of conjunctivo-limbal autograft after wide excision of primary and recurrent pterygia.

METHODS

Twenty-one eyes of 18 patients with primary pterygium and 18 eyes of 18 patients with recurrent pteygium underwent conjunctivo-limbal autograft after wide excision of pterygium. All patients underwent follow-up for more than six months. Recurrence rates and complications were evaluated.

RESULTS

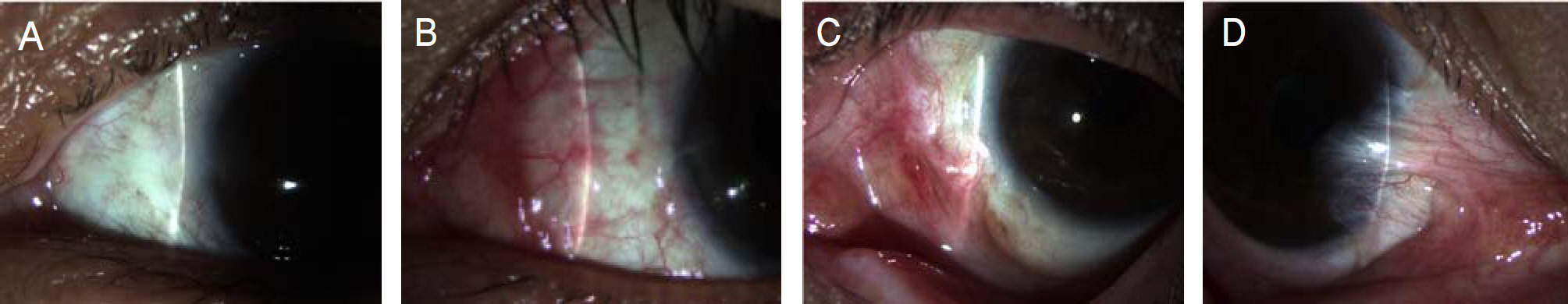

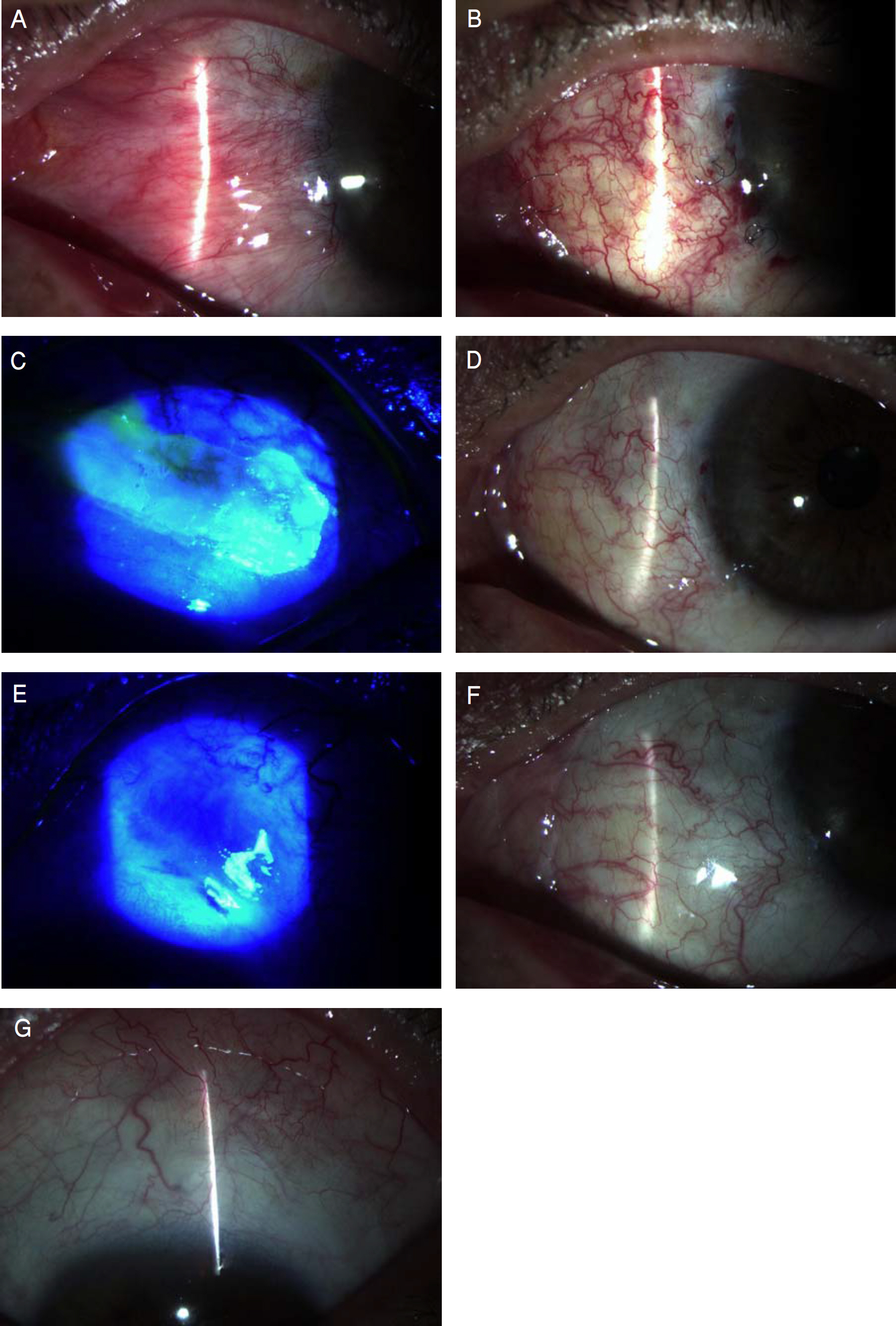

With a minimum of six months of follow-up, fibrovascular tissue in the excised area, not invading the cornea, was noted in one eye (5.6%) in the recurrent pterygium group but no further surgical interventions for the cosmetic problem were needed. One eye (4.8%) showed wound dehiscence, three eyes (14.3%) showed subgraft hemorrhage, and one eye (4.8%) showed subconjunctival fibrosis at the donor site in the primary pterygium group, while two eyes (11.1%) showed subgraft hemorrhage, and one eye (5.6%) showed Tenon's Capsule granuloma at the donor site in the recurrent pterygium group.

CONCLUSIONS

Conjunctivo-limbal autograft after wide excision of pterygium can be considered an effective treatment with low recurrence rates for both primary and recurrent pterygia.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Recurrence Rates of Amniotic Membrane Transplantation, Conjunctival Autograft and Conjunctivolimbal Autograft in Primary Pterygium

Chang Hyun Kim, Jin Kee Lee, Dae Jin Park

J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2009;50(12):1780-1788. doi: 10.3341/jkos.2009.50.12.1780.

Reference

-

References

1. Dushku N, John MK, Schultz GS, Reid TW. Pterygia pathogenesis: corneal invasion by matrix metalloproteinase expressing altered limbal epithelial basal cells. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001; 119:695–706.2. Sakoonwatanyoo P, Tan DT, Smith DR. Expression of p63 in pterygium and normal conjunctiva. Cornea. 2004; 23:67–70.

Article3. Solomon A, Grueterich M, Li DQ, et al. Overexpression of Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-2 in pterygium body fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003; 44:573–80.

Article4. Di Girolamo N, McCluskey P, Lloyd A, et al. Expression of MMPs and TIMPs in human pterygia and cultured pterygium epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000; 41:671–9.5. Li DQ, Lee SB, Gunja-Smith Z, Liu Y, et al. Overexpression of collagenase (MMP-1) and stromelysin (MMP-3) by pterygium head fibroblasts. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001; 119:71–80.6. Dushku N, Hatcher SL, Albert DM, Reid TW. p53 expression and relation to human papillomavirus infection in pingueculae, pterygia, and limbal tumors. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999; 117:1593–9.

Article7. Threlfall TJ, English DR. Sun exposure and pterygium of the eye: a dose-response curve. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999; 128:280–7.

Article8. Tsai YY, Cheng YW, Lee H, et al. Oxidative DNA damage in pterygium. Mol Vis. 2005; 11:71–5.9. Jurgenliemk-Schulz IM, Hartman LJ, Roesink JM, et al. Prevention of pterygium recurrence by postoperative single-dose beta-irradiation: a prospective randomized clinical double-blind trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004; 59:1138–47.10. Liddy BS, Morgan JF. Triethylene thiophosphoramide (thio-tepa) and pterygium. Am J Ophthalmol. 1966; 61:888–90.11. Segev F, Jaeger-Roshu S, Gefen-Carmi N, Assia EI. Combined mitomycin C application and free flap conjunctival autograft in pterygium surgery. Cornea. 2003; 22:598–603.

Article12. Sharma A, Gupta A, Ram J, Gupta A. Low-dose intraoperative mitomycin-C versus conjunctival autograft in primary pterygium surgery: long term follow-up. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2000; 31:301–7.

Article13. Kenyon KR, Wagoner MD, Hettinger ME. Conjunctival autograft transplantation for advanced and recurrent pterygium. Ophthalmology. 1985; 92:1461–70.

Article14. Dadeya S, Malik KP, Gullian BP. Pterygium surgery: conjunctival rotation autograft versus conjunctival autograft. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2002; 33:269–74.

Article15. Ahn DG, Auh SJ, Choi YS. The clinical results of limbal conjunctival autograft transplantation with intraoperative mitomycin c application for recurrent pterygia. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1999; 40:2443–9.16. Tan DT, Chee SP, Dear KB, et al. Effect of pterygium morphology on pterygium recurrence in a controlled trial comparing conjunctival autografting with bare sclera excision. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997; 115:1235–40.

Article17. Guler M, Sobaci G, Ilker S, et al. Limbal-conjunctival autograft transplantation in cases with recurrent pterygium. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1994; 72:721–6.18. Al Fayez MF. Limbal versus conjunctival autograft transplantation for advanced and recurrent pterygium. Ophthalmology. 2002; 109:1752–5.

Article19. Gris O, Guell JL, del Campo Z. Limbal-conjunctival autograft transplantation for the treatment of recurrent pterygium. Ophthalmology. 2000; 107:270–3.

Article20. Allan BD, Short P, Crawford GJ, et al. Pterygium excision with conjunctival autografting: an effective and safe technique. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993; 77:698–701.

Article21. Oh TH, Choi KY, Yoon BJ. The effect of conjunctival autograft for recurrent pterygium. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1994; 35:1335–9.22. Shimazaki J, Yang HY, Tsubota K. Limbal autograft transplantation for recurrent and advanced pterygia. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1996; 27:917–23.

Article23. Ti SE, Tseng SC. Management of primary and recurrent pterygium using amniotic membrane transplantation. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002; 13:204–12.

Article24. Solomon A, Pires RT, Tseng SC. Amniotic membrane transplantation after extensive removal of primary and recurrent pterygia. Ophthalmology. 2001; 108:449–60.

Article25. Ma DH, See LC, Hwang YS, Wang SF. Comparison of amniotic membrane graft alone or combined with intraoperative mitomycin C to prevent recurrence after excision of recurrent pterygia. Cornea. 2005; 24:141–50.

Article26. Prabhasawat P, Barton K, Burkett G, Tseng SC. Comparison of conjunctival autografts, amniotic membrane grafts, and primary closure for pterygium excision. Ophthalmology. 1997; 104:974–85.

Article27. Koh YM, Kim JY, Ji NC. A comparative study of recurrence rate in bilateral pterygium surgery: conjunctival autograft transplantation versus bare scleral. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2001; 42:1543–8.28. Cho JW, Chung SH, Seo KY, Kim EK. Conjunctival mini-flap technique and conjunctival autotransplantation in rterygium surgery. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2005; 46:1471–7.29. Mutlu FM, Sobaci G, Tatar T, Yildirim E. A comparative study of recurrent pterygium surgery: limbal conjunctival autograft transplantation versus mitomycin C with conjunctival flap. Ophthalmology. 1999; 106:817–21.

Article30. Ti SE, Chee SP, Dear KB, Tan DT. Analysis of variation in success rates in conjunctival autografting for primary and recurrent pterygium. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000; 84:385–9.

Article31. Oh TH, Choi KY, Yoon BJ. The effect of conjunctival autograft for recurrent pterygium. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1994; 35:1335–9.32. Kim YS, Kim JH, Byun YJ. Limbal-conjunctival autograft transplantation for the treatment of primary pterygium. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1999; 40:1804–10.33. Davis DB 2nd, Mandel MR. Posterior peribulbar anesthesia: an alternative to retrobulbar anesthesia. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1989; 37:59–61.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Effectiveness of Wide Excision of Subconjucntival Fibrovascular Tissue with Conjunctivo-Limbal Autograft in Pterygium Surgery

- Long-term Outcomes of Conjunctivo-limbal Autograft Alone and Additional Widening of Limbal Incision in Recurrent Pterygia

- Analysis of Donor-site Complications after Conjunctivo-limbal Autograft to Treat Pterygium

- Efficacy of Subconjunctival Bevacizumab Injection after Pterygium Excision with Limbal Conjunctival Autograft in Recurred Pterygium

- Changes in Eye Movement Amplitude after Conjunctivo-Limbal Autograft in Patients with Recurrent Pterygium, Ocular Motility Restriction