J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2010 Sep;51(9):1292-1297. 10.3341/jkos.2010.51.9.1292.

A Case of Bilateral Papilledema and Visual Field Defect in Pediatric Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Eulji University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. se1106@hanmail.net

- 2Department of Pediatrics, Eulji University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2122300

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2010.51.9.1292

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To report a case of bilateral papilledema and visual field defect in pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

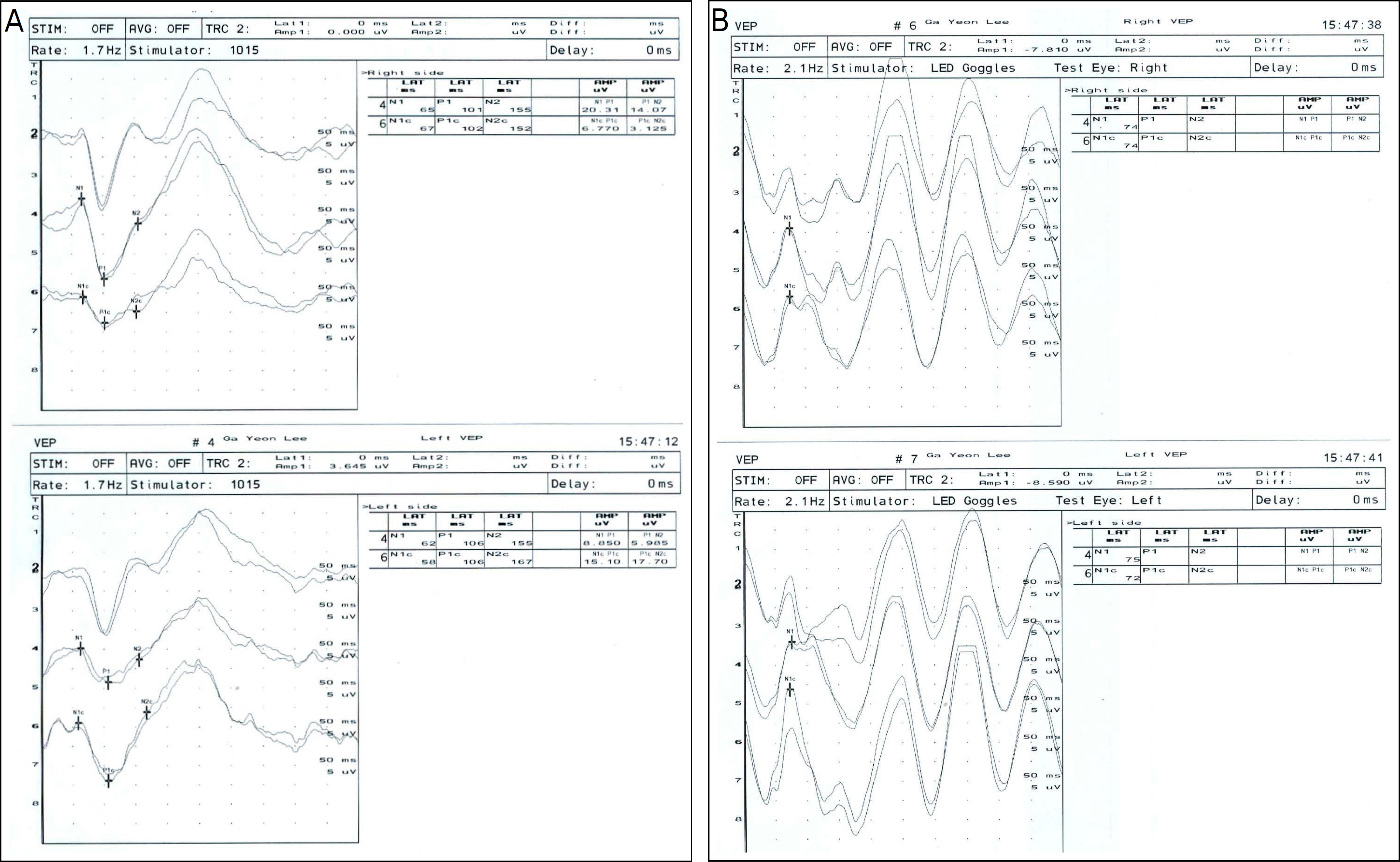

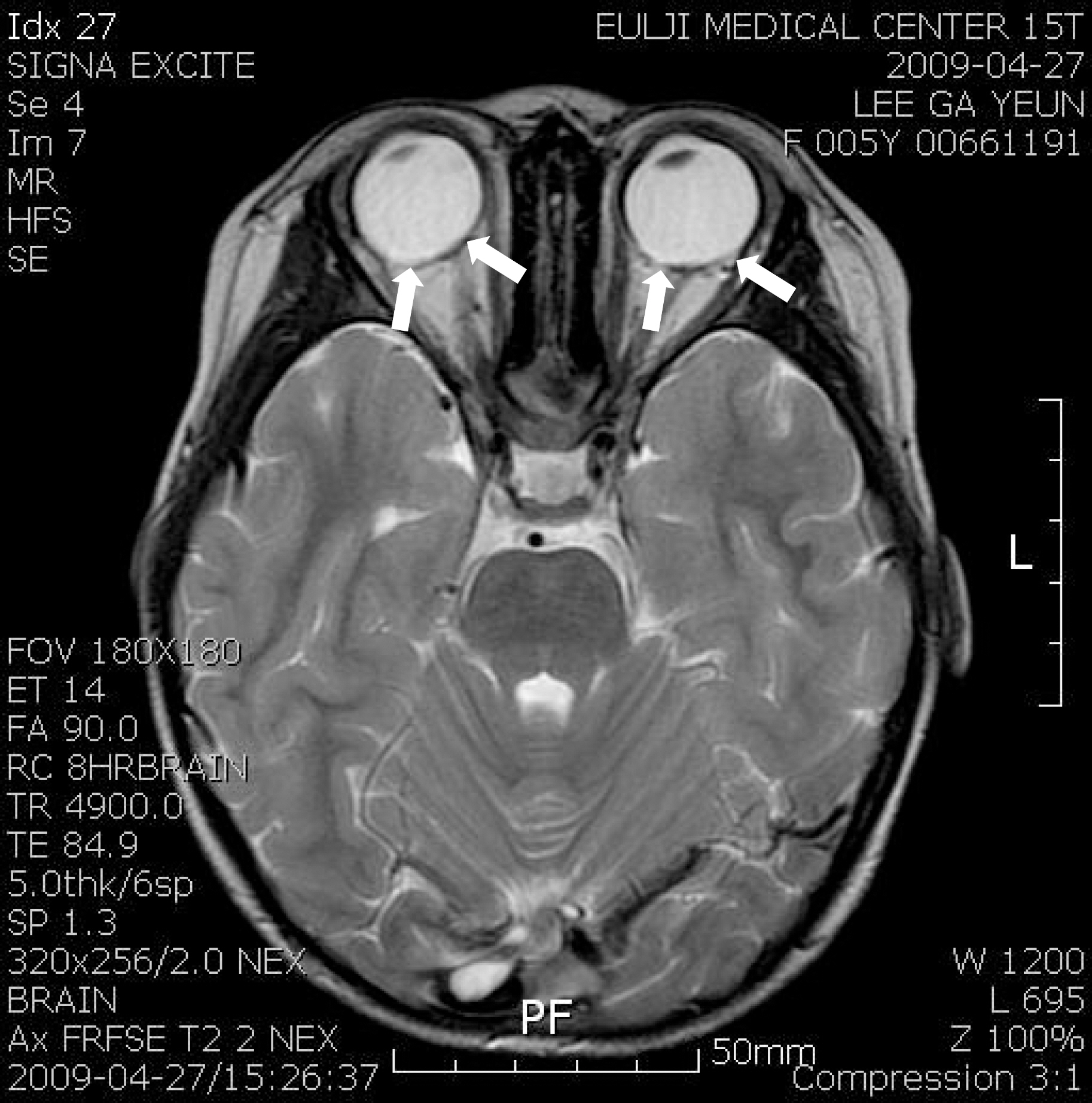

CASE SUMMARY

The 5-year-old female patient was admitted to the hospital, complaining of headache and vomiting of 3 weeks duration. After admission, she complained of diplopia. The uncorrected visual acuity was 0.3 in the right eye and 0.8 in the left. An alternative prism cover test showed approximately 35 PD esotropia, with a -2 abduction limitation of both eyes. Fundus examination showed bilateral papilledema and peripapillary retinal hemorrhages. No abnormality was found in the MRI and CT, symptoms of headache, vomiting, bilateral papilledema, and esotropia with normal neurologic examination. Therefore, she was diagnosed with pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension. In Humphrey visual field test, MD was -14.15 dB in right and -16.58 dB in the left eye. Also, the general sensitivity of visual field decreased. Acetazolamide (Diamox(R)) was given orally for 30 days. Forty-four days after the initial visit, peripapillary retinal hemorrhages and vessel tortuosity decreased. Furthermore, visual acuity improved to 1.0 in the right eye and 0.9 in the left. The esotropia reduced to 5 PD, and MD improved to -4.83 dB in the right eye and -5.24 dB in the left.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Rangwala LM, Liu GT. Pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007; 52:597–617.

Article2. Acheson JF. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension and visual function. Br Med Bull. 2006; 79–80:233–44.

Article3. Friedman DI. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2007; 11:62–8.

Article4. Wolf A, Hutcheson KA. Advances in evaluation and management of pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2008; 19:391–7.

Article5. Friedman DI. Papilledema and pseudotumor cerebri. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2001; 14:129–47.6. Kesler A, Fattal-Valevski A. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in the pediatric population. J Child Neurol. 2002; 17:745–8.

Article7. Genizi J, Lahat E, Zelnik N, et al. Childhood-onset idiopathic intracranial hypertension: relation of sex and obesity. Pediatr Neurol. 2007; 36:247–9.

Article8. Phillips PH, Repka MX, Lambert SR. Pseudotumor cerebri in children. J AAPOS. 1998; 2:33–8.

Article9. Babikian P, Corbett J, Bell W. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in children: the Iowa experience. J Child Neurol. 1994; 9:144–9.

Article10. Cinciripini GS, Donahue S, Borchert MS. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in prepubertal pediatric patients: characteristics, treatment, and outcome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999; 127:178–82.

Article11. Salman MS, Kirkham FJ, MacGregor DL. Idiopathic “benign” intracranial hypertension: case series and review. J Child Neurol. 2001; 16:465–70.

Article12. Lessell S, Rosman NP. Permanent visual impairment in childhood pseudotumor cerebri. Arch Neurol. 1986; 43:801–4.

Article13. Baker RS, Carter D, Hendrick EB, Buncic JR. Visual loss in pseudotumor cerebri of childhood. A follow-up study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985; 103:1681–6.14. Corbett JJ, Savino PJ, Thompson HS, et al. Visual loss in pseudotumor cerebri. Follow-up of 57 patients from five to 41 years and a profile of 14 patients with permanent severe visual loss. Arch Neurol. 1982; 39:461–74.

Article15. Wall M, George D. Visual loss in pseudotumor cerebri. Incidence and defects related to visual field strategy. Arch Neurol. 1987; 44:170–5.16. Corbett JJ, Nerad JA, Tse DT, Anderson RL. Results of optic nerve sheath fenestration for pseudotumor cerebri: the lateral orbitotomy approach. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988; 106:1391–7.17. Dersh J, Schlezinger NS. Inferior nasal quadrantanopia in pseudotumor cerebri. Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1959; 84:116–8.18. Randhawa S, Van Stavern GP. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2008; 19:445–53.

Article19. Distelmaier F, Sengler U, Messing-Juenger M, et al. Pseudotumor cerebri as an important differential diagnosis of papilledema in children. Brain Dev. 2006; 28:190–5.

Article20. Weisberg LA, Chutorian AM. Pseudotumor cerebri of childhood. Am J Dis Child. 1977; 131:1243–8.

Article21. Nichelli P, Penne A. Permanent inferior binasal quadrantanopsia in pseudotumor cerebri. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1983; 4:221–4.

Article22. Lecks H, Baker D. Pseudotumor cerebri-an Allergic phenomenon? A discussion of 17 cases including two of infants manifesting pseudotumor while receiving soybean feedings. Clin Pediatr. 1965; 4:32–7.23. Rush JA. Pseudotumor cerebri: clinical profile and visual outcome in 63 patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980; 55:541–6.24. Michael CB, Michael V. Magnetic resonance imaging in pseudotumor cerebri. Ophthalmology. 1998; 105:1683–93.

Article25. Agid R, Willinsky RA, Mikulis DJ, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: the validity of cross-sectional neuroimaging signs. Neuroradiology. 2006; 48:521–7.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Associated with Obesity

- Intracranial Hypotension Leading to Intracranial Hypertension with Ocular Manifestations

- A Case of Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension with Papilledema Secondary to Recombinant Human Growth Hormone Treatment

- Pseudopapilledema Combined with Idiopathic Papilledema in a Child Receiving Growth Hormone Treatment

- A Case of Bilateral Papilledema Resulted from the Use of Oral Contraceptives