Korean J Obstet Gynecol.

2010 Jan;53(1):1-14. 10.5468/kjog.2010.53.1.1.

Clinical implications of nuchal translucency

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. drmaxmix.choi@samsung.com

- KMID: 2077954

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5468/kjog.2010.53.1.1

Abstract

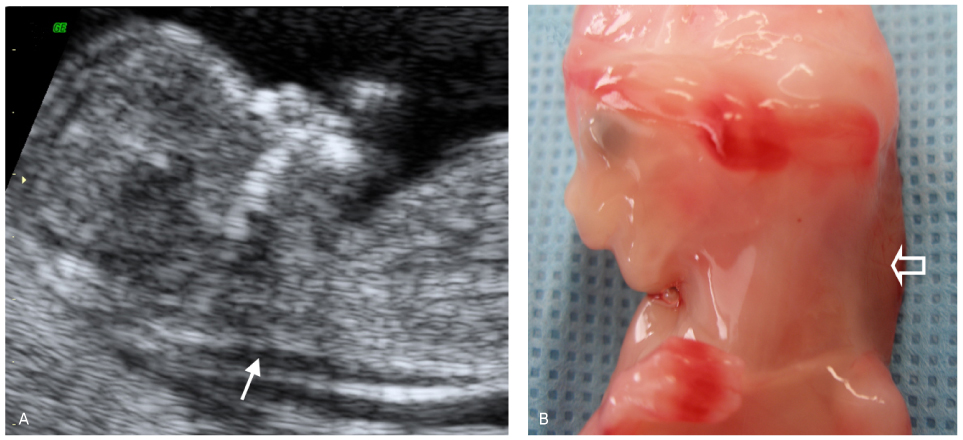

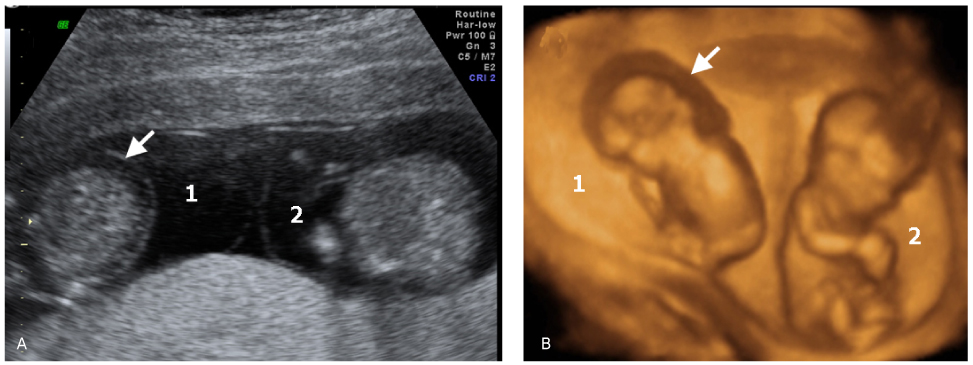

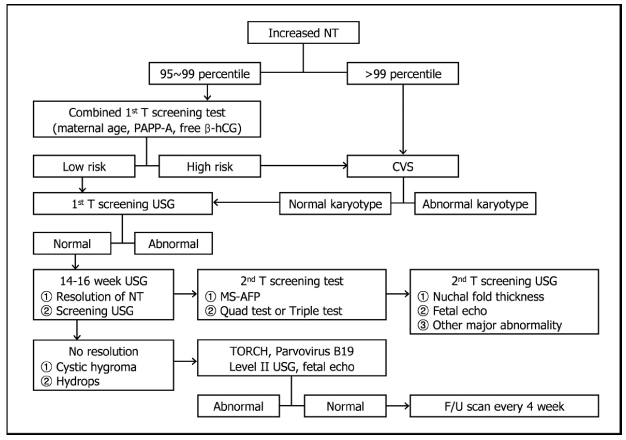

- Fetal nuchal translucency (NT) is an echolucent space between the dorsal edge of soft tissue of the fetal neck and the linear echo of the skin observed in a midsagittal image measured at 11 to 13(+6) weeks of gestation. Increased NT (>95 percentile) is highly associated with fetal aneuploidy and congenital structural anomalies including congenital heart defects. In combination with maternal serum PAPP-A and free beta-hCG, increased NT has been demonstrated to provide efficient Down syndrome risk assessment, with a detection rate of 80-87% (5% false-positive rate), and it also allows earlier diagnosis of fetal aneuploidy. Even in the absence of aneuploidy, increased NT is still associated with an increase in adverse perinatal outcome including abortion, fetal death and a variety of fetal malformations. This paper will review the mechanism of increased NT, correct measurement of NT, and recent evidences for interpretation and management for the fetuses with increased NT.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Efficacy of fetal cardiac axis evaluation in the first trimester as a screening tool for congenital heart defect or aneuploidy

Youn-Joon Jung, Bo-Ra Lee, Gwang Jun Kim

Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2020;63(3):278-285. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2020.63.3.278.

Reference

-

1. Sheppard C, Platt LD. Nuchal translucency and first trimester risk assessment: a systematic review. Ultrasound Q. 2007. 23:107–116.3. Nicolaides KH, Azar G, Byrne D, Mansur C, Marks K. Fetal nuchal translucency: ultrasound screening for chromosomal defects in first trimester of pregnancy. BMJ. 1992. 304:867–869.4. Koos BJ. First-trimester screening: lessons from clinical trials and implementation. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2006. 18:152–155.5. Souka AP, Von Kaisenberg CS, Hyett JA, Sonek JD, Nicolaides KH. Increased nuchal translucency with normal karyotype. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005. 192:1005–1021.6. Snijders RJ, Noble P, Sebire N, Souka A, Nicolaides KH. UK multicentre project on assessment of risk of trisomy 21 by maternal age and fetal nuchal-translucency thickness at 10-14 weeks of gestation. Fetal Medicine Foundation First Trimester Screening Group. Lancet. 1998. 352:343–346.7. Malone FD, Canick JA, Ball RH, Nyberg DA, Comstock CH, Bukowski R, et al. First-trimester or second-trimester screening, or both, for Down's syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005. 353:2001–2011.8. Wald NJ, Rodeck C, Hackshaw AK, Walters J, Chitty L, Mackinson AM. First and second trimester antenatal screening for Down's syndrome: the results of the Serum, Urine and Ultrasound Screening Study (SURUSS). J Med Screen. 2003. 10:56–104.9. Wapner R, Thom E, Simpson JL, Pergament E, Silver R, Filkins K, et al. First-trimester screening for trisomies 21 and 18. N Engl J Med. 2003. 349:1405–1413.10. Wald NJ, Rodeck C, Hackshaw AK, Rudnicka A. SURUSS in perspective. BJOG. 2004. 111:521–531.11. Haak MC, van Vugt JM. Pathophysiology of increased nuchal translucency: a review of the literature. Hum Reprod Update. 2003. 9:175–184.12. Mol BW. Down's syndrome, cardiac anomalies, and nuchal translucency. Fetal heart failure might link nuchal translucency and Down's syndrome. BMJ. 1999. 318:70–71.13. Hyett J, Perdu M, Sharland G, Snijders R, Nicolaides KH. Using fetal nuchal translucency to screen for major congenital cardiac defects at 10-14 weeks of gestation: population based cohort study. BMJ. 1999. 318:81–85.14. Montenegro N, Matias A, Areias JC, Castedo S, Barros H. Increased fetal nuchal translucency: possible involvement of early cardiac failure. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1997. 10:265–268.15. Rizzo G, Muscatello A, Angelini E, Capponi A. Abnormal cardiac function in fetuses with increased nuchal translucency. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003. 21:539–542.16. Haak MC, Twisk JW, Bartelings MM, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, van Vugt JM. First-trimester fetuses with increased nuchal translucency do not show altered intracardiac flow velocities. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005. 25:246–252.17. Simpson JM, Sharland GK. Nuchal translucency and congenital heart defects: heart failure or not? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000. 16:30–36.18. Bekker MN, Haak MC, Rekoert-Hollander M, Twisk J, Van Vugt JM. Increased nuchal translucency and distended jugular lymphatic sacs on first-trimester ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005. 25:239–245.19. Bekker MN, van den Akker NM, Bartelings MM, Arkesteijn JB, Fischer SG, Polman JA, et al. Nuchal edema and venous-lymphatic phenotype disturbance in human fetuses and mouse embryos with aneuploidy. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2006. 13:209–216.20. Nicolaides KH. First-trimester screening for chromosomal abnormalities. Semin Perinatol. 2005. 29:190–194.21. NTQR Web site 2006. Accessed November 20, 2006. Available from: https://www.ntqr.org/SM/Provider/wfProviderInformation.aspx https://www.ntqr.org/SM/Provider/wfProviderInformation.aspx.22. Pandya PP, Snijders RJ, Johnson SP, De Lourdes Brizot M, Nicolaides KH. Screening for fetal trisomies by maternal age and fetal nuchal translucency thickness at 10 to 14 weeks of gestation. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995. 102:957–962.23. Chung JH, Yang JH, Song MJ, Cho JY, Lee YH, Park SY, et al. The distribution of fetal nuchal translucency thickness in normal Korean fetuses. J Korean Med Sci. 2004. 19:32–36.24. Kim MH, Park SH, Cho HJ, Choi JS, Kim JO, Ahn HK, et al. Threshold of nuchal translucency for the detection of chromosomal aberration: comparison of different cut-offs. J Korean Med Sci. 2006. 21:11–14.25. Spencer K, Bindra R, Nix AB, Heath V, Nicolaides KH. Delta-NT or NT MoM: which is the most appropriate method for calculating accurate patient-specific risks for trisomy 21 in the first trimester? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003. 22:142–148.26. Azar GB, Snijders RJ, Gosden C, Nicolaides KH. Fetal nuchal cystic hygromata: associated malformations and chromosomal defects. Fetal Diagn Ther. 1991. 6:46–57.27. Molina FS, Avgidou K, Kagan KO, Poggi S, Nicolaides KH. Cystic hygromas, nuchal edema, and nuchal translucency at 11-14 weeks of gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 2006. 107:678–683.29. Brizot ML, Snijders RJ, Bersinger NA, Kuhn P, Nicolaides KH. Maternal serum pregnancy- associated plasma protein A and fetal nuchal translucency thickness for the prediction of fetal trisomies in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1994. 84:918–922.30. Noble PL, Abraha HD, Snijders RJ, Sherwood R, Nicolaides KH. Screening for fetal trisomy 21 in the first trimester of pregnancy: maternal serum free beta-hCG and fetal nuchal translucency thickness. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1995. 6:390–395.31. Spencer K, Crossley JA, Aitken DA, Nix AB, Dunstan FD, Williams K. Temporal changes in maternal serum biochemical markers of trisomy 21 across the first and second trimester of pregnancy. Ann Clin Biochem. 2002. 39(Pt 6):567–576.33. Nicolaides KH. Nuchal translucency and other first-trimester sonographic markers of chromosomal abnormalities. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004. 191:45–67.34. Nicolaides KH, Spencer K, Avgidou K, Faiola S, Falcon O. Multicenter study of first-trimester screening for trisomy 21 in 75 821 pregnancies: results and estimation of the potential impact of individual risk-orientated two-stage first-trimester screening. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005. 25:221–226.35. Orlandi F, Rossi C, Orlandi E, Jakil MC, Hallahan TW, Macri VJ, et al. First-trimester screening for trisomy-21 using a simplified method to assess the presence or absence of the fetal nasal bone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005. 192:1107–1111.36. Matias A, Gomes C, Flack N, Montenegro N, Nicolaides KH. Screening for chromosomal abnormalities at 10-14 weeks: the role of ductus venosus blood flow. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998. 12:380–384.37. Borrell A. The ductus venosus in early pregnancy and congenital anomalies. Prenat Diagn. 2004. 24:688–692.39. Huggon IC, DeFigueiredo DB, Allan LD. Tricuspid regurgitation in the diagnosis of chromosomal anomalies in the fetus at 11-14 weeks of gestation. Heart. 2003. 89:1071–1073.40. Faiola S, Tsoi E, Huggon IC, Allan LD, Nicolaides KH. Likelihood ratio for trisomy 21 in fetuses with tricuspid regurgitation at the 11 to 13+6-week scan. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005. 26:22–27.41. Falcon O, Auer M, Gerovassili A, Spencer K, Nicolaides KH. Screening for trisomy 21 by fetal tricuspid regurgitation, nuchal translucency and maternal serum free beta-hCG and PAPP-A at 11+0 to 13+6 weeks. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006. 27:151–155.42. Borrell A. Promises and pitfalls of first trimester sonographic markers in the detection of fetal aneuploidy. Prenat Diagn. 2009. 29:62–68.43. Cicero S, Avgidou K, Rembouskos G, Kagan KO, Nicolaides KH. Nasal bone in first-trimester screening for trisomy 21. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006. 195:109–114.44. Senat MV, Frydman R. [Increased nuchal translucency with normal karyotype]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2007. 35:507–515.45. Bilardo CM, Müller MA, Pajkrt E, Clur SA, van Zalen MM, Bijlsma EK. Increased nuchal translucency thickness and normal karyotype: time for parental reassurance. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007. 30:11–18.46. Maymon R, Weinraub Z, Herman A. Pregnancy outcome of euploid fetuses with increased nuchal translucency: how bad is the news? J Perinat Med. 2005. 33:191–198.48. Souka AP, Krampl E, Bakalis S, Heath V, Nicolaides KH. Outcome of pregnancy in chromosomally normal fetuses with increased nuchal translucency in the first trimester. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001. 18:9–17.49. Souka AP, Snijders RJ, Novakov A, Soares W, Nicolaides KH. Defects and syndromes in chromosomally normal fetuses with increased nuchal translucency thickness at 10-14 weeks of gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998. 11:391–400.50. Michailidis GD, Economides DL. Nuchal translucency measurement and pregnancy outcome in karyotypically normal fetuses. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001. 17:102–105.51. Smrcek JM, Gembruch U, Krokowski M, Berg C, Krapp M, Geipel A, et al. The evaluation of cardiac biometry in major cardiac defects detected in early pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003. 268:94–101.52. Vogel M, Sharland GK, McElhinney DB, Zidere V, Simpson JM, Miller OI, et al. Prevalence of increased nuchal translucency in fetuses with congenital cardiac disease and a normal karyotype. Cardiol Young. 2009. 19:441–445.53. Clur SA, Mathijssen IB, Pajkrt E, Cook A, Laurini RN, Ottenkamp J, et al. Structural heart defects associated with an increased nuchal translucency: 9 years experience in a referral centre. Prenat Diagn. 2008. 28:347–354.54. Hoffman JI, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002. 39:1890–1900.55. Atzei A, Gajewska K, Huggon IC, Allan L, Nicolaides KH. Relationship between nuchal translucency thickness and prevalence of major cardiac defects in fetuses with normal karyotype. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005. 26:154–157.56. McAuliffe FM, Fong KW, Toi A, Chitayat D, Keating S, Johnson JA. Ultrasound detection of fetal anomalies in conjunction with first-trimester nuchal translucency screening: a feasibility study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005. 193(3 Pt 2):1260–1265.57. Makrydimas G, Sotiriadis A, Ioannidis JP. Screening performance of first-trimester nuchal translucency for major cardiac defects: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003. 189:1330–1335.58. Westin M, Saltvedt S, Bergman G, Almstrom H, Grunewald C, Valentin L. Is measurement of nuchal translucency thickness a useful screening tool for heart defects? A study of 16,383 fetuses. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006. 27:632–639.59. Makrydimas G, Sotiriadis A, Huggon IC, Simpson J, Sharland G, Carvalho JS, et al. Nuchal translucency and fetal cardiac defects: a pooled analysis of major fetal echocardiography centers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005. 192:89–95.60. Maiz N, Plasencia W, Dagklis T, Faros E, Nicolaides K. Ductus venosus Doppler in fetuses with cardiac defects and increased nuchal translucency thickness. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008. 31:256–260.61. Haak MC, Twisk JW, Bartelings MM, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, van Vugt JM. Ductus venosus flow velocities in relation to the cardiac defects in first-trimester fetuses with enlarged nuchal translucency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003. 188:727–733.62. Favre R, Cherif Y, Kohler M, Kohler A, Hunsinger MC, Bouffet N, et al. The role of fetal nuchal translucency and ductus venosus Doppler at 11-14 weeks of gestation in the detection of major congenital heart defects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003. 21:239–243.63. Senat MV, De Keersmaecker B, Audibert F, Montcharmont G, Frydman R, Ville Y. Pregnancy outcome in fetuses with increased nuchal translucency and normal karyotype. Prenat Diagn. 2002. 22:345–349.64. Senat MV, Bussières L, Couderc S, Roume J, Rozenberg P, Bouyer J, et al. Long-term outcome of children born after a first-trimester measurement of nuchal translucency at the 99th percentile or greater with normal karyotype: a prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007. 196:53.e1–53.e6.65. Sebire NJ, Snijders RJ, Hughes K, Sepulveda W, Nicolaides KH. Screening for trisomy 21 in twin pregnancies by maternal age and fetal nuchal translucency thickness at 10-14 weeks of gestation. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996. 103:999–1003.66. Spencer K, Nicolaides KH. Screening for trisomy 21 in twins using first trimester ultrasound and maternal serum biochemistry in a one-stop clinic: a review of three years experience. BJOG. 2003. 110:276–280.67. Spencer K. Screening for trisomy 21 in twin pregnancies in the first trimester using free beta-hCG and PAPP-A, combined with fetal nuchal translucency thickness. Prenat Diagn. 2000. 20:91–95.68. Cleary-Goldman J, Berkowitz RL. First trimester screening for Down syndrome in multiple pregnancy. Semin Perinatol. 2005. 29:395–400.69. Platt LD. First-trimester risk assessment: twin gestations. Semin Perinatol. 2005. 29:258–262.70. Sepulveda W, Sebire NJ, Hughes K, Kalogeropoulos A, Nicolaides KH. Evolution of the lambda or twin-chorionic peak sign in dichorionic twin pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 1997. 89:439–441.71. Vandecruys H, Faiola S, Auer M, Sebire N, Nicolaides KH. Screening for trisomy 21 in monochorionic twins by measurement of fetal nuchal translucency thickness. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005. 25:551–553.72. Wald NJ, Rish S, Hackshaw AK. Combining nuchal translucency and serum markers in prenatal screening for Down syndrome in twin pregnancies. Prenat Diagn. 2003. 23:588–592.73. Spencer K. Screening for trisomy 21 in twin pregnancies in the first trimester: does chorionicity impact on maternal serum free beta-hCG or PAPP-A levels? Prenat Diagn. 2001. 21:715–717.74. Sebire NJ, Souka A, Skentou H, Geerts L, Nicolaides KH. Early prediction of severe twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2000. 15:2008–2010.75. Maslovitz S, Yaron Y, Fait G, Gull I, Wolman I, Jaffa A, et al. Feasibility of nuchal translucency in triplet pregnancies. J Ultrasound Med. 2004. 23:501–504.76. Maymon R, Dreazen E, Tovbin Y, Bukovsky I, Weinraub Z, Herman A. The feasibility of nuchal translucency measurement in higher order multiple gestations achieved by assisted reproduction. Hum Reprod. 1999. 14:2102–2105.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Changes of Nuchal Translucency in Early Normal Fetuses

- Fetal Nuchal Translucency Measurement for Detection of Chromosomal Abnormalities in the First Trimester of High Risk Pregnancy

- Prenatal chromosomal microarray analysis of fetus with increased nuchal translucency

- Nuchal Translucency Measurement in Normal Fetuses at 10 - 14 Weeks of Gestation I

- Management of pregnancies with increased fetal nuchal translucency in the first trimester