Tuberc Respir Dis.

2007 Nov;63(5):435-439. 10.4046/trd.2007.63.5.435.

A Case of Pyrazinamide Induced Fulminant Hepatic Failure

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Kosin University, Busan, Korea. jangtw@ns.kosinmed.or.kr

- 2Department of Radiology, College of Medicine, Kosin University, Busan, Korea.

- KMID: 2050477

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4046/trd.2007.63.5.435

Abstract

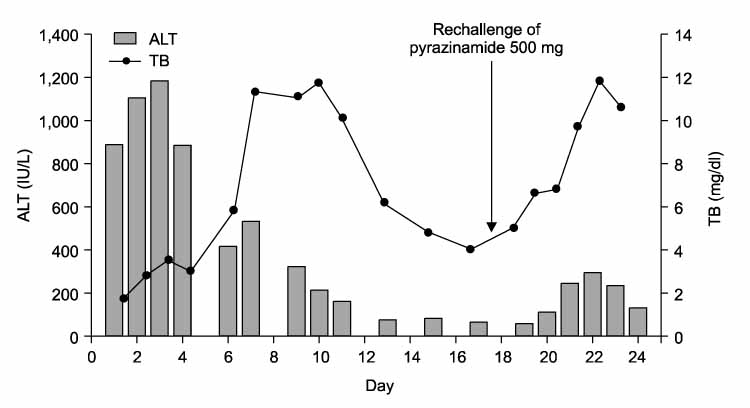

- Standard antituberculous therapy, including isoniazid (INH), rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide (PZA), is widely used to treat active tuberculosis. The most important side effect is hepatotoxicity. In a standard four-drug regimen, PZA was the most common cause of drug-induced hepatitis and was dose-related. The incidence of drug-induced hepatitis is high at doses of 40~70 mg/kg per day but has fallen significantly since the recommended dose was reduced. Liver toxicity induced by PZA is rare at doses of 25 mg/kg per day or less. PZA-induced fulminant hepatic failure is also rare but fatal. We report a case of fulminant hepatic failure caused by a re-challenge of PZA.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Singapore Tuberculosis Service/British Medical Research Council. Clinical trial of three 6-month regimens of chemotherapy given intermittently in the continuation phase in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985. 132:374–378.2. Singapore Tuberculosis Service/British Medical Research Council. Clinical trial of six-month and four-month regimens of chemotherapy in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979. 119:579–585.3. Third East African/British Medical Research Councils study. Controlled clinical trial of four short-course regimens of chemotherapy for two durations in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis: first report: Third East African/British Medical Research Councils study. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978. 118:39–48.4. Danan G, Pessayre D, Larrey D, Benhamou JP. Pyrazinamide fulminant hepatitis: an old hepatotoxin strikes again. Lancet. 1981. 2:1056–1057.5. Yee D, Valiquette C, Pelletier M, Parisien I, Rocher I, Menzies D. Incidence of serious side effects from first-line antituberculosis drugs among patients treated for active tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003. 167:1472–1477.6. McElroy PD, Ijaz K, Lambert LA, Jereb JA, Iademarco MF, Castro KG, et al. National survey to measure rates of liver injury, hospitalization, and death associated with rifampin and pyrazinamide for latent tuberculosis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2005. 41:1125–1133. Erratum in: Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:313.7. Ormerod LP, Skinner C, Wales J. Hepatotoxicity of antituberculosis drugs. Thorax. 1996. 51:111–113.8. Joint Tuberculosis Committee of the British Thoracic Society. Chemotherapy and management of tuberculosis in the United Kingdom: recommendations 1998. Thorax. 1998. 53:536–548.9. Blumberg HM, Burman WJ, Chaisson RE, Daley CL, Etkind SC, Friedman LN, et al. American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control/Infectious Diseases Society of America. Treatment of tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003. 167:603–662.10. Schaberg T, Rebhan K, Lode H. Risk factors for side-effect of isoniazide, rifampin and pyrazinamide in patients hospitalized for pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 1996. 9:2026–2030.11. Lee AM, Mennone JZ, Jones RC, Paul WS. Risk factors for hepatotoxicity associate with rifampin and pyrazinamide for the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection: experience from three pubic health tuberculosis clinics. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002. 6:995–1000.12. Smink F, van Hoek B, Ringers J, van Altena R, Arend SM. Risk factors of acute hepatic failure during antituberculosis treatment: two cases and literature review. Neth J Med. 2006. 64:377–384.13. Thompson NP, Caplin ME, Hamilton MI, Gillespie SH, Clarke SW, Burroughs AK, McIntyre N. Anti-tuberculosis medication and the liver: dangers and recommendations in management. Eur Respir J. 1995. 8:1384–1388.14. Durand F, Bernuau J, Pessayre D, Samuel D, Belaiche J, Degott C, et al. Deleterious influence of pyrazinamide on the outcome of patients with fulminant or subfulminant liver failure during antituberculous treatment including isoniazid. Hepatology. 1995. 21:929–932.15. Idilman R, Ersoz S, Coban S, Kumbasar O, Bozkaya H. Antituberculous therapy-induced fulminant hepatic failure: successful treatment with liver transplantation and nonstandard antituberculous therapy. Liver Transpl. 2006. 12:1427–1430.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Three Cases of Fulminant Hepatic Failure due to Congestive Heart Failure

- One case of fulminant hepatic failure related to Dictamnus dasycarpus

- A Case of Fulminant Hepatic Failure Secondary to Hepatic Metastasis of Small Cell Lung Carcinoma

- A case of fulminant hepatic failure complicating hepatitis A virus superinfection in a hepatitis B virus carrier

- A Case of Thrombocytopenia and Purpura Induced by Rifamnpin, Pyrazinamide, and Ciprofloxacin