J Korean Diabetes Assoc.

2006 Sep;30(5):388-397. 10.4093/jkda.2006.30.5.388.

Titration with an Initially Lower Dose Increased Compliance of Cilostazol (Pletaal(R)) in Diabetic Patients

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Eulji University College of Medicine, Korea.

- KMID: 2008269

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4093/jkda.2006.30.5.388

Abstract

-

BACKGROUND: Headache is frequently reported by patients using cilostazol, which is a potent inhibitor of platelet aggregation with vasodilatory effects, for preventing atherosclerotic disease. The aims of this study were to think out a dosing schedule for improving compliance on headache and to investigate the possible mechanisms of headache associated with atherosclerosis measured as carotid intimal-media thickness (IMT) in Korean diabetic patients.

METHODS

We therefore randomized patients into three groups according to the different dosing regimens for 6 weeks (1) group 1; 50 mg once daily, followed by 50 mg twice daily, and then 100 mg twice daily or (2) group 2; 50 mg twice daily, followed by 100 mg twice daily or (3) group 3; 100 mg twice daily without titration. We evaluated severity of the headache by visual analog scaled (VAS) symptom score from zero to ten and measured carotid IMT using high resolution ultrasound.

RESULTS

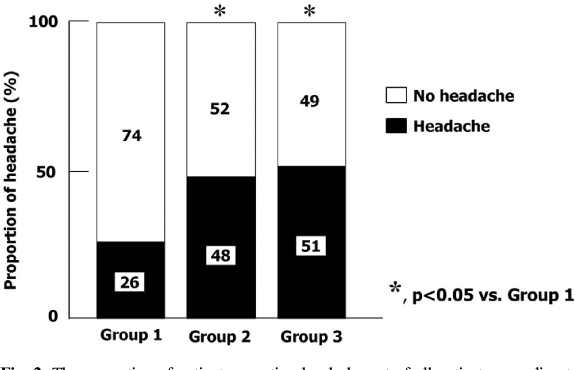

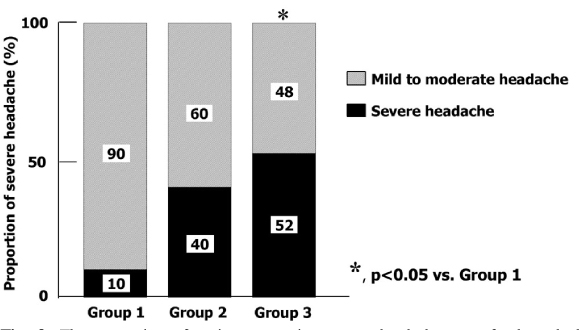

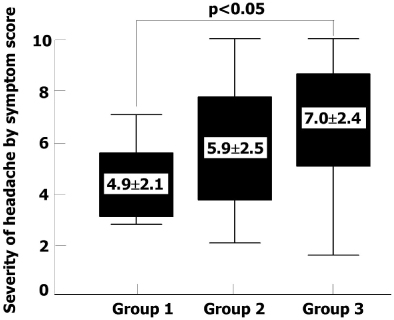

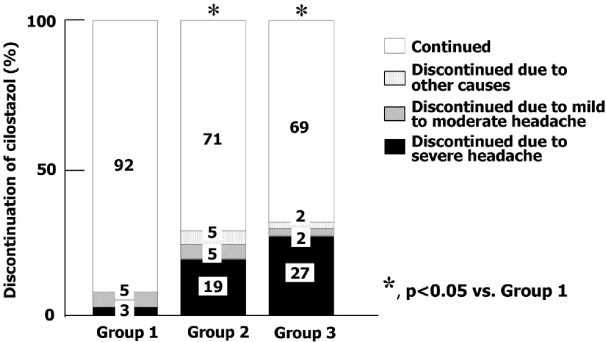

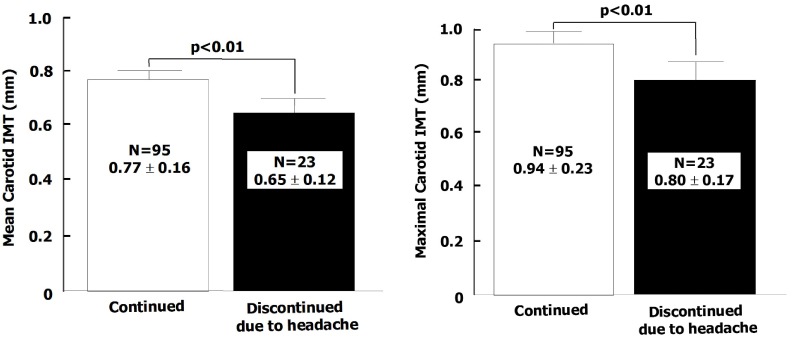

A total of 122 diabetic patients were analyzed. The mean values of age, sex, duration of diabetes, BMI, HbA1c, lipid profiles, blood pressure, and smoking were not different among three groups. The proportion of headache was significantly lower in group 1 than group 2 and 3 (26% vs. 48% and 51%, P < 0.05). The proportion of severe headache was significantly lower in group 1 than group 2 and 3 (3% vs. 19% , 27%, P < 0.05). Among patients who had headache, the proportion of severe headache was significantly lower in group 1 than group 3. (10% vs. 52%, P < 0.05). The VAS symptom score of headache was significantly lower in group 1 than group 3 (4.9+/-2.1 vs. 7.0+/-2.4, P < 0.05). The proportion of the discontinuation of medication due to headache was significantly lower in group 1 than other two groups (8% vs. 24% and 29%, P < 0.05). The patients who had discontinued medication due to headache had lower carotid IMT than in whom were tolerable (Mean carotid IMT; 0.65+/-0.12 vs. 0.77+/-0.16 mm, P < 0.01, Maximal carotid IMT; 0.80+/-0.17 vs. 0.94+/-0.23 mm, P < 0.01). The proportion of patients who had discontinued medication due to headache was significantly lower in group 1 than other two groups (8% vs. 24%, 29%, P < 0.05]

CONCLUSION

Titration with an initially lower dose of cilostazol could be considered to reduce the proportion and severity of headache and thereby increase compliance. Atherosclerosis estimated as carotid IMT may contribute to the tolerability of cilostazol.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Beckman JA, Creager MA, Libby P. Diabetes and atherosclerosis-Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Management. JAMA. 2002. 287:2570–2581.2. Colwell JA, Nesto RW. The platelet in diabetes: Focus on prevention of ischemic events. Diabetes care. 2003. 26:2181–2188.3. American Diabetes Association. Aspirin therapy in diabetes (Position Statement). Diabetes Care. 2003. 26:Suppl. 1. S87–S88.4. Liu Y, Cone J, Le SN, Fong M, Tao L, Shoaf SE, Bricmont P, Czerwiec FS, Kambayashi J, Yoshitake M, Sun B. Cilostazol and dipyridamole synergistically inhibit human platelet aggregation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004. 44:266–273.5. Kawata M, Kuramoto E, Kataoka T, Saito A, Adachi K, Matsuura A, Sakamoto S. Comparative inhibitory effects of cilostazol and ticlopidine on subacute stent thrombosis and platelet function in acute myocardial infarction patients with percutaneous coronary intervention. Int Heart J. 2005. 46:13–22.6. Comerota AJ. Effect on platelet function of cilostazol, clopidogrel, and aspirin, each alone or in combination. Atheroscler Suppl. 2005. 6:13–19.7. Liu Y, Shakur Y, Yoshitake M, Kambayashi JJ. Cilostazol (pletal): a dual inhibitor of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase type 3 and adenosine uptake. Cardiovas Drug Rev. 2001. 19:369–386.8. Elam MB, Heckman J, Crouse JR. Effect of the novel antiplatelet agent cilostazol on plasma lipoproteins in patients with intermittent claudication. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998. 18:1942–1947.9. Wang T, Elam MB, Forbes WP, Zhong J, Nakajima K. Reduction of remnant lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations by cilostazol in patients with intermittent claudication. Atherosclerosis. 2003. 171:337–342.10. Mitsuhashi N, Tanaka Y, Kubo S, Ogawa A, Hayashi C, Uchino H, Shimizu T, Watada H, Kawasumi M, Onuma T, Kawamoti R. Effects of cilostazol, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, on carotid IMT in Japanese type 2 diabetic patients. Endocr J. 2004. 51:545–550.11. Ahn CW, Lee HC, Park SW, Song YD, Huh KB, Oh SJ, Kim YS, Choi YK, Kim JM, Lee TH. Decrease in carotid intima media thickness after 1 year of cilostazol treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Ptact. 2001. 52:45–53.12. Shinoda-Tagawa T, Yamasaki Y, Yoshida S, Kajimoto Y, Tsujino T, Hakui N, Matsumoto M, Hori M. A phosphodiesterase inhibitor, cilostazol, prevents the onset of silent brain infarction in Japanese subjects with Type II diabetes. Diabetologia. 2002. 45:188–194.13. Pratt CM. Analysis of the cilostazol safety database. Am J Cardiol. 2001. 87:28D–33D.14. Thompson PD, Zimet R, Forbes WP, Zhang P. Meta-analysis of results from eight randomized, placebo-controlled trials on the effect of cilostazol on patients with intermittent claudication. Am J Cardiol. 2002. 90:1314–1319.15. Yamashita K, Kobayashi S, Okada K, Tsunematsu T. Increased external carotid artery blood flow in headache patients induced by cilostazol. Preliminary communication. Arzneimittelforchung. 1990. 40:587–588.16. Birk S, Kruuse C, Peterson KA, Jonassen O, Tfelt-Hansen P, Olesen J. The phosphodiesterase 3 inhibitor cilostazol dilates large cerebral arteries in humans without affecting regional cerebral blood flow. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004. 24:1352–1358.17. Jarvisalo MJ, Lehtimaki T, Raitakari OT. Determinants of arterial nitrate-mediated dilatation in children. Role of oxidized low-density lipoprotein, endothelial function, and carotid intima-media thickness. Circulation. 2004. 109:2885–2889.18. Jungnickel PW, Maloley PA, Vander Tuin EL, Peddicord TE, Campbell JR. Effect of two aspirin pretreatment regimens on niacin-induced cutaneous reactions. J Gen Intern Med. 1997. 12:591–596.19. Iversen HK, Olsen J, Tfelt-Hansen P. Intravenous nitroglycerin as an experimental model of vascular headache. Basic characteristics. Pain. 1989. 38:17–24.22. Gnasso A, Irace C, Mattioli PL, Pujia A. Carotid intima-media thickness and coronary heart disease risk factors. Atherosclerosis. 1996. 119:7–15.23. Allan PL, Mowbray PI, Lee AJ, Fowkes GR. Relationship between carotid intima-media thickness and symptomatic and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease. The Edinburgh Artery Study. Stroke. 1997. 28:348–353.24. Beebe HG, Dawson DL, Cutler BS, Herd JA, Stradness DE, Bortey EB, Forbes WP. A new pharmacological treatment for intermittent claudication. Arch Intern Med. 1999. 159:2041–2050.25. Sorkin EM, Markham A. Cilostazol. Drugs Aging. 1999. 14:63–71.26. Kimura Y, Tani T, Kanbe T, Watanabe K. Effect of cilostazol on platelet aggregation and experimental thrombosis. Arzneimittelforschung. 1985. 35:1144–1149.27. Samra SS, Bajaj P, Vijayaraghavan KS, Potdar NP, Vyas D, Devani RG, Ballary C, Desai A. Efficacy and safety of cilostazol, a novel phosphodiesterase inhibitor in patients with intermittent claudication. J Indian Med Assoc. 2003. 101:561–564.28. Chapman TM, Goa KL. Cilostazol: a review of its use in intermittent claudication. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2003. 3:117–138.29. Cariski AT. Cilostazol: a novel treatment option in intermittent claudication. Int J Clin Prat Supl. 2001. 119:11–18.30. Reilly MP, Mohler ER 3rd. Cilostazol: treatment of intermittent claudication. Ann Pharmacother. 2001. 35:48–56.31. Money SR, Herd JA, Isaacsohn JL, Davidson M, Cutler B, Herkman J, Forbes WP. Effect of cilostazol on walking distances in patients with intermittent claudication caused by peripheral vascular disease. J Vasc Surg. 1998. 27:267–274.32. Iida O, Nanto S, Uematsu M, Morozumi T, Kotani J, Awata M, Onishi T, Ito N, Oshima F, Minamiguchi H, Kitakaze M, Nagata S. Cilostazol reduces target lesion revascularization after percutaneous transluminal angioplasty in the femoropopliteal artery. Circ J. 2005. 69:1256–1259.33. Ahn JC, Song WH, Kwon JA, Park CG, Seo HS, Oh DJ, Rho YM. Effects of cilostazol on platelet activation in coronary stenting patients who already treated with aspirin and clopidogrel. Korean J Intern Med. 2004. 19:230–236.34. Goto S. Cilostazol: potential mechanism of action for antithrombotic effects accompanied by a low rate of bleeding. Atheroscler Suppl. 2005. 6:3–11.35. Uehara S, Hirayama A. Effects of cilostazol on platelet function. Arzneimittelforschung. 1985. 35:1531–1534.36. Yamazaki M, Uchiyama S, Xiong Y, Nakano T, Nakamura T, Iwata M. Effect of remnant-like particle on shear-induced platelet activation and its inhibition by antiplatelet agents. Thromb Res. 2005. 115:211–218.37. Lee TM, Su SF, Tsai CH, Lee YT, Wang SS. Differential effects of cilostazol and pentoxifylline on vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with intermittent claudication. Clin Sci. 2001. 101:305–311.38. Mizutani M, Okuda Y, Yamashita K. Effect of cilostazol on the production of platelet-derived growth factor in cultured human vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Mol Med. 1996. 57:156–158.39. Shin HK, Kim YK, Kim KY, Lee JH, Hong KW. Remnant lipoprotein particles induce apoptosis in endothelial cells by NAD(P)H oxidase-mediated production of superoxide and cytokines via lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 activation. Prevention by cilostazol. Circulation. 2004. 109:1022–1028.40. Pueyo ME, Chen Y, D'Angelo G, Michel JB. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression by cAMP in rat aortic smooth muscle cells. Exp Cell Res. 1998. 238:354–358.41. Kim MJ, Park KG, Lee KM, Kim HS, Kim SY, Kim CS, Lee SL, Chang YC, Park JY, Lee KU, Lee IK. Cilostazol inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell growth by downregulation of the transcription factor E2F. Hypertension. 2005. 45:552–556.42. Ikeda U, Ikeda M, Kano S, Kanbe T, Shimada K. Effects of cilostazol, a cAMP phosphodiesterase inhibitor, on nitric oxide production by vascular smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996. 314:197–202.43. Birk S, Petersen KA, Kruuse C, Guieu R, Jonassen O, Eisert W, Olesen J. The effect of circulating adenosine on cerebral haemodynamics and headache generation in healthy subjects. Cephalagia. 2005. 25:369–377.44. Lindgren A, Husted S, Staaf G, Ziegler B. Dipyridamole and headache-a pilot study of initial dose titration. J Neurol Sci. 2004. 223:179–184.45. Evans RW, Kruuse C. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors and migraine. Headache. 2004. 44:925–926.46. Evans RW. Sildenafil can trigger cluster headaches. Headache. 2006. 46:173–174.47. Borchard U. Calcium antagonists in comparison: view of the pharmacologist. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1994. 24:S85–S91.48. Iversen HK, Nielson TH, Garre K, Tfelt-Hansen P, Olesen J. Dose-dependent headache response and dilatation of limb and extracranial arteries after three doses of 5-isosorbide-mononitrate. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1992. 42:31–35.49. Kruuse C, Jacobsen TB, Lassen LH, Thomsen LL, Hasselbalch SG, Dige-Petersen H, Olesen J. Dipyridamole dilates large cerebral arteries concomittant to headache induction in healthy subjects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000. 20:1372–1379.50. Tzourio C, Gagnière B, El Amrani M, Alpérovitch A, Bousser M-G. Relationship between migraine, blood pressure and carotid thickness. A population-based study inthe elderly. Cephalalgia. 2003. 23:914–920.51. Labropoulos N, Ashraf Mansour M, Kang SS, Oh DS, Buckman J, Baker WH. Viscoelastic properties of normal and atherosclerotic carotid arteries. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2000. 19:221–225.52. Hasen P, Mangell P, Sonesson B, Lanne T. Diameter and compliance in the human common carotid artery-variations with age and sex. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1995. 21:1–9.53. Safar ME. Carotid artery stiffness with applications to cardiovascular pharmacology. Gen Pharmac. 1996. 27:1293–1302.54. Alan S, Ulgen MS, Akdeniz S, Alan B, Toprak N. Intima-media thickness and arterial distensibility in Bechet's disease. Angiology. 2004. 55:413–419.55. Posadzy-Malaczynska A, Kosch M, Hausberg M, Rahn KH, Stanisic G, Malaczynski P, Gluszek J, Tykarski A. Arterial distensibility, intima media thickness and pulse wave velocity after renal transplantation and in dialysis normotensive patients. Int Angiol. 2005. 24:89–94.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Therapeutic effects of cilostazol(pletaal) in patients with occlusive arterial diseases

- Oral Administration of Cilostazol Increases Ocular Blood Flow in Patients with Diabetic Retinopathy

- Clinical Effect of Cilostazol in Diabetic Patients with Peripheral Vascular Disease

- Efficacy of Topiramate Using Lower Dose and Slower Dose-Titration in Refractory Partial Epilepsies: A Multicenter Open Clinical Trial

- A Study on the Relationship of Perceived Self-efficacy and Sick-role behavioral Compliance in Diabetic children