Dement Neurocogn Disord.

2014 Mar;13(1):16-19. 10.12779/dnd.2014.13.1.16.

Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2 with Only Clinical Feature of Memory Impairment: Case Report

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Neurology, SVH Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. astro76@naver.com

- KMID: 1973685

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.12779/dnd.2014.13.1.16

Abstract

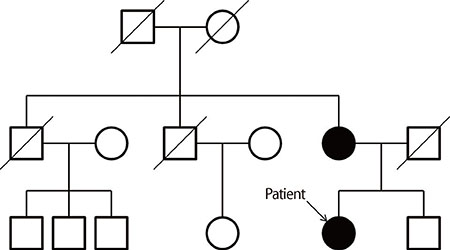

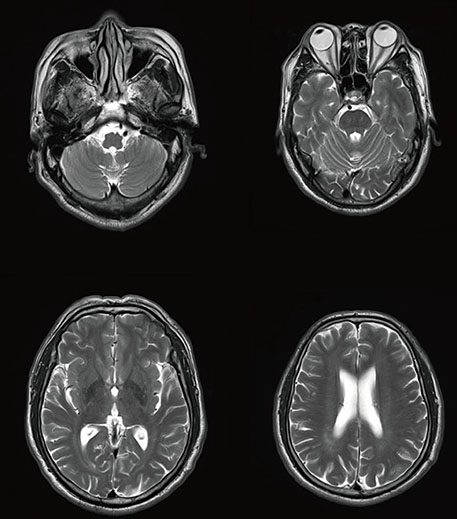

- Spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) is one of a group of genetic disorders characterized by slowly progressive incoordination of gait and often associated with poor coordination of hands, speech, and eye movements. There are more than 35 different types of spinocerebellar ataxias, each caused by a different genetic mutation. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2) is a subtype of type I autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (ADCA type I) characterized by truncal ataxia, dysarthria, slowed saccades and less commonly ophthalmoparesis and chorea. The age at onset varies from 3 to 79 years (mean 33). Usually, the first symptom of the disease is the gait ataxia, followed by the cerebellar dysarthria. Of late, other clinical manifestations of SCA2 are the cognitive dysfunctions, which include frontal executive impairment, verbal short-term memory deficits as well as reduction of attention and concentration. We report a 56-year old woman identified as spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2) with only clinical feature of memory impairment.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. McMurtray AM, Clark DG, Flood MK, Perlman S, Mendez MF. Depressive and Memory Symptoms as Presenting Features of Spinocerebellar Ataxia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006; 18:420–422.

Article2. Orozco Diaz G, Nodarse FR, Cordoves S, Augurger G. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia: clinical analysis of 263 patients from a homogenous population in Holguin, Cuba. Neurology. 1990; 40:1369–1375.3. Schols L, Gispert M, Vorgerd M, Menezes Vieira-Saecher AM, Blanke P, Auburger G, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2: genotype and phenotype in German kindreds. Arch Neurol. 1997; 54:1073–1080.4. Harding AE. The clinical features and classification of the late onset autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias: a study of 11 families, including descendants of the 'the Drew family of Walworth'. Brain. 1982; 105:1–28.

Article5. Pulst SM, Nechiporuk A, Nechiporuk T, Gispert S, Chen XN, Lopes-Cendes I, et al. Moderate expansion of a normally biallelic trinucleotide repeat in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. Nat Genet. 1996; 14:269–276.

Article6. Kang YW. A normative study of the Korean-Mini Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) in the elderly. Korean J Psychol. 2006; 25:1–12.7. Kang YW, Na DL. Seoul neuropsychological screening battery. Incheon: Human Brain Research & Consulting Co.;2003.8. Teive HAG, Arruda WO. Cognitive dysfunction in spinocerebellar ataxias. Dement Neuropsychol. 2009; 3:180–187.

Article9. Schmahmann JD. Disorders of the cerebellum: ataxia, dysmetria of thought, and the cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004; 16:367–378.

Article10. Yang Y, Kim JE, Lee JS, Kim S. Akinetic Mutism and Cognitive-Affective Syndrome Caused by Unilateral PICA Infarction. J Clin Neurol. 2007; 3:192–196.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 7 with Torticollis

- Craniocervical Segmental Dystonia in the Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2

- Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 8 Presenting as Ataxia without Definite Cerebellar Atrophy

- A Case of Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 6 Presenting Downbeat Nystagmus Alone

- A Case of Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 28