Korean Circ J.

2007 Nov;37(11):559-566. 10.4070/kcj.2007.37.11.559.

Quinidine-Induced QTc Interval Prolongation and Gender Differences in Healthy Korean Subjects

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Research Institute, Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Inje University, Busan, Korea. dongskim@inje.ac.kr

- 2Pharmacology and Pharmacogenomics Research Center, College of Medicine, Inje University, Busan, Korea.

- KMID: 1909617

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2007.37.11.559

Abstract

-

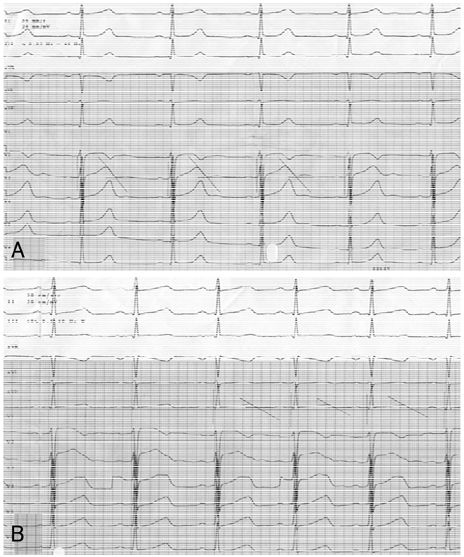

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES: Drug-induced electrocardiographic QT interval prolongation is associated with the occurrence of a potentially lethal form of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, termed 'torsades de pointes' (TdP). Women are at greater risk for the development of drug-induced TdP. To determine whether this may be the result of gender-specific differences in the effect of quinidine on cardiac repolarization, we compared the degree of quinidine-induced QT interval lengthening in young, healthy volunteers.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

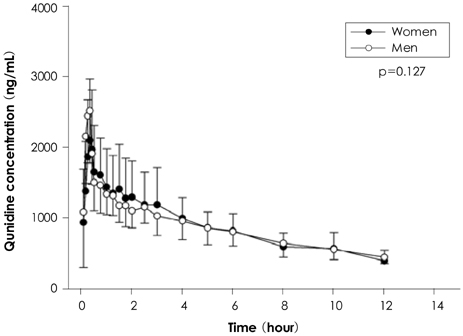

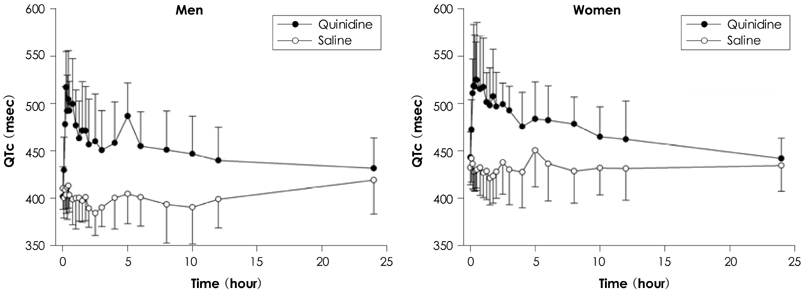

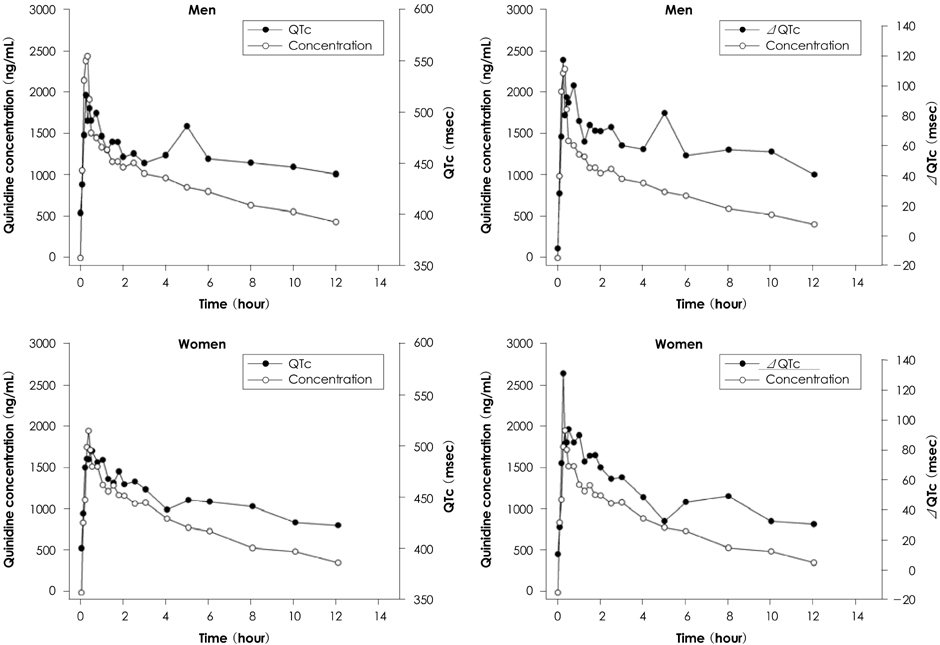

Twelve women and 12 men each received a single intravenous dose of quinidine (4 mg/kg) or placebo in a single-blinded, randomized crossover trial. Total plasma concentrations of quinidine were measured, and QT and corrected QT intervals were analyzed.

RESULTS

As expected, the mean QTc interval at baseline was longer for women than for men (443.6+/-26.9 vs 402.1+/-31.3 msec, respectively, p=0.037). The mean value of the maximal DeltaQTc after quinidine infusion was higher in women (134.4+/-46.4 vs 117.5+/-37.7 msec, respectively, p=0.029), and the mean value of the minimal DeltaQTc for 1 hour after quinidine infusion was also higher in the female group (47.6+/-15.7 vs 83.7+/-25.4 msec, p=0.034). However, there were no significant differences in the time courses of the changes in the quinidine-induced QTc and DeltaQTc interval between the two groups (p=0.092, and p=0.305, respectively).

CONCLUSION

Quinidine causes greater QT prolongation in women at equivalent serum concentrations. This difference may contribute to the greater incidence of drug-induced TdP observed in women taking quinidine, and has implications for other cardiac and noncardiac drugs that prolong the QTc interval.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Napolitano C, Priori SG, Schwartz PJ. Torsade de pointes: mechanisms and management. Drugs. 1994. 47:51–65.2. Dessertenne F. Ventricular tachycardia with 2 variable opposing foci. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1966. 59:263–272.3. Makkar RR, Fromm BS, Steinman RT, Meissner MD, Lehmann MH. Female gender as a risk factor for torsades de pointes associated with cardiovascular drugs. JAMA. 1993. 270:2590–2597.4. Thompson KA, Murray JJ, Blair IA, Woosley RL, Roden DM. Plasma concentrations of quinidine, its major metabolites, and dihydroquinidine in patients with torsades de pointes. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988. 43:636–642.5. Drici MD, Burklow TR, Wang WX, Chen Y, Glazer R, Woosley R. Sex steroid hormonal influences upon QT response to quinidine. Circulation. 1995. 92:Suppl. I434.6. Drici MD, Knollmann BC, Wang WX, Woosley RL. Cardiac actions of erythromycin: influence of female sex. JAMA. 1998. 280:1774–1776.7. Brandsteterova E, Romanova D, Kralikova D, Bozekova L, Kriska M. Automatic solid-phase extraction determination and high-performance luquid chromatographic determination of quinidine in plasma. J Chromatogr A. 1994. 665:101–104.8. Nielson F, Kramer K, Brsen K. Determination of quinidine, dihydroquinidine, (3S)-hydroxyquinidine and quinidine N-oxide in plasma and urine by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl. 1994. 660:103–110.9. Bazett HC. An analysis of the times relations of electrocardiograms. Heart. 1918. 7:353–370.10. Mirvis DM. Spatial variation of the QT intervals in normal persons and patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985. 5:625–631.11. Algra A, Tijssen JG, Roelandt JR, Pool J, Lubsen J. QTc prolongation measured by standard 12-lead electrocardiogram is an independent risk factor for sudden death due to cardiac arrest. Circulation. 1991. 83:1888–1894.12. Kim JY, Rhee YM, Ahn SK, Lee MH, Kim SS. A case of torsades de pointes induced by cisapride. Korean Circ J. 1999. 29:994–998.13. Kim SK, Jeon JW, Kim CH, Lee SW, Choi TM, Kwon YJ. Two cases of torsades de pointes after astemizole overdose. Korean Circ J. 1996. 26:593–597.14. Oh SK, Kuk H, Lim SB, Jeong JW, Park YK, Park OK. Torsades de pointes after treatment with terfenadine and ketoconazole. Korean Circ J. 1998. 28:458–462.15. Roden DM, Woosley RL, Primm RK. Incidence and clinical features of the quinidine-associated long QT syndrome: implications for patient care. Am Heart J. 1986. 111:1088–1093.16. Belhassen B, Viskin S, Antzelevitch C. The Brugada syndrome: is an implantable cardioverter defibrillator the only therapeutic option? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002. 25:1634–1640.17. Schimpf R, Wolpert C, Gaita F, Giustetto C, Borggrefe M. Short QT syndrome. Cardiovasc Res. 2005. 67:357–366.18. Rautaharju PM, Zhou SH, Wong S, et al. Sex differences in the evolution of the electrocardiographic QT interval with age. Can J Cardiol. 1992. 8:690–695.19. Liu XK, Katchman A, Drici MD, et al. Gender difference in the cycle length-dependent QT and potassium currents in rabbits. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998. 285:672–679.20. Drici MD, Burklow TR, Haridasse V, Glazer RI, Woosley RL. Sex hormones prolong the QT interval and downregulate potassium channel expression in the rabbit heart. Circulation. 1996. 94:1471–1474.21. de Beer EL, Keizer HA. Direct action of estradiol-17 beta on the atrial action potential. Steroids. 1982. 40:223–231.22. Knollmann B, Ender SI, Franz MR, Woosley RL. Acute effects of 17-β-estradiol and dihydrotestosterone on action potential duration and QT-interval in isolated rabbit hearts. J Invest Med. 1996. 44:209A. Abstract.23. Yeola SW, Rich TC, Uebele VN, Tamkun MM, Snyders DJ. Molecular analysis of a binding site for quinidine in a human cardiac delayed rectifier K+ channel: role of S6 in antiarrhythmic drug binding. Circ Res. 1996. 78:1105–1114.24. Lehmann MH, Hardy S, Archibald D, Quart B, MacNeil DJ. Sex difference in risk of torsade de pointes with d.l-sotalol. Circulation. 1996. 94:2535–2541.25. Waldo AL, Camm AJ, deRuyter H, et al. Effect of d-sotalol on mortality in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after recent and remote myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1996. 348:7–12.26. Drici MD, Knollmann BC, Wang WX, Woosley RL. Cardiac actions of erythromycin: influence of female sex. JAMA. 1998. 280:1774–1776.27. Antzelevitch C, Sun ZQ, Zhang ZQ, Yan GX. Cellular and ionic mechanisms underlying erythromycin-induced long QT intervals and torsade de pointes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996. 28:1836–1848.28. Lehmann MH, Hardy S, Archibald D, MacNeil DJ. JTc prolongation with d, l-sotalol in women versus men. Am J Cardiol. 1999. 83:354–359.29. Reinoehl J, Frankovich D, Machado C, et al. Probucol-associated tachyarrhythmic events and QT prolongation: importance of gender. Am Heart J. 1996. 131:1184–1191.30. Le Coz F, Funck-Brentano C, Poirier JM, Kibleur Y, Mazoit FX, Jaillon P. Prediction of sotalol-induced maximum steady-state QTc prolongation from single-dose administration in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992. 52:417–426.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- QTc prolongation in patients with COVID-19: a retrospective chart review

- Clinical Correlates of QTc Prolongation in Patients with Schizophrenia : A Retrospective Study

- A Case of QTc Interval Prolongation Associated With Quetiapine

- Relationship between Abdominal Obesity and Electrocardiographic QTc Interval Prolongation

- Relationship between Metabolic Syndrome and QTc Interval Prolongation