J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg.

2015 Jun;41(3):149-155. 10.5125/jkaoms.2015.41.3.149.

Transmasseteric antero-parotid facelift approach for open reduction and internal fixation of condylar fractures

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Wonkwang University School of Dentistry, Iksan, Korea. omschoi@wonkwang.ac.kr

- KMID: 1797846

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5125/jkaoms.2015.41.3.149

Abstract

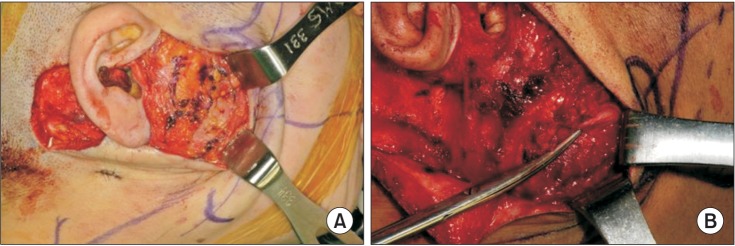

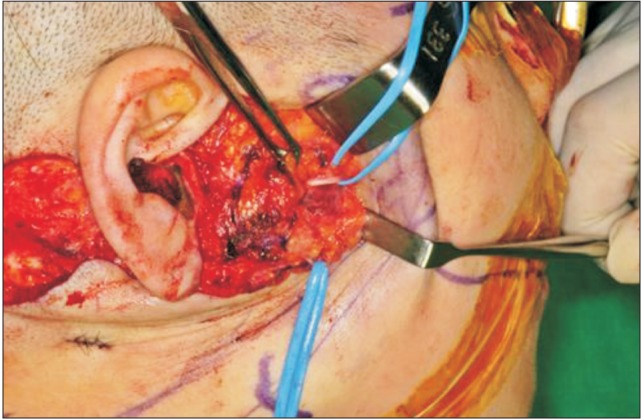

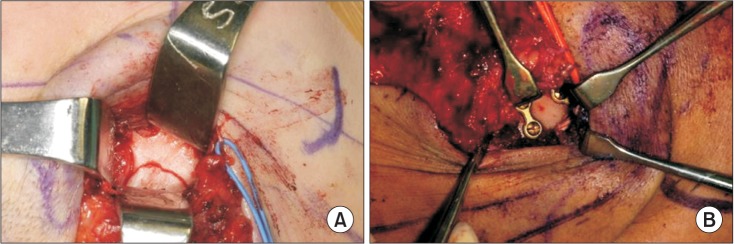

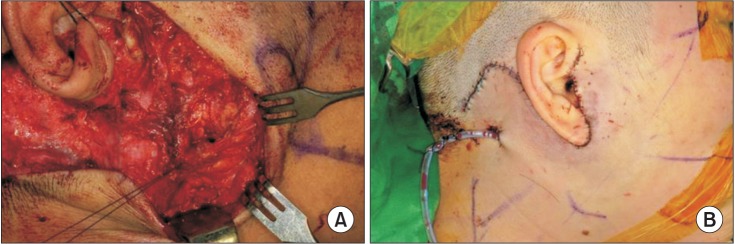

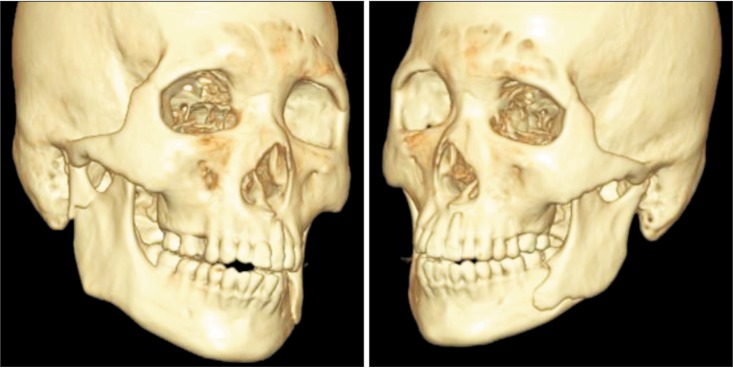

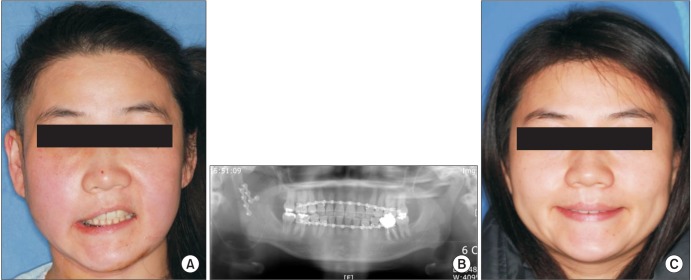

- Surgical approaches to the condylar fracture include intraoral, preauricular, submandibular, and retromandibular approaches. Each approach has its own advantages and disadvantages. When a patient needs esthetic results and an intraoral approach is not feasible, the transmasseteric antero-parotid facelift approach is considered. This approach permits direct exposure and allow the surgeon to fixate the fractured unit tangentially. Tangential fixation is critical to osteosynthesis. Disadvantages of the transmasseteric antero-parotid facelift approach include damage to the facial nerve and a longer operation time. However, after the initial learning curve, facial nerve damage can be avoided and operation time may decrease. We report three cases of subcondylar fractures that were treated with a transmasseteric antero-parotid facelift approach. Among these, two cases had trivial complications that were easily overcome. Instead of dissecting through the parotid gland parenchyma, the transmasseteric antero-parotid facelift approach uses transmasseteric dissection and reduces facial nerve damage more than the retromandibular transparotid approach. The esthetic result is superior to that of other approaches.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Divaris M, Blugerman G, Paul MD. Face expressive lifting (FEL): an original surgical concept combined with bipolar radiofrequency. Eur J Plast Surg. 2014; 37:69–76. PMID: 24465090.

Article2. Lindahl L. Condylar fractures of the mandible. I. Classification and relation to age, occlusion, and concomitant injuries of teeth and teeth-supporting structures, and fractures of the mandibular body. Int J Oral Surg. 1977; 6:12–21. PMID: 402318.3. Lee C, Mueller RV, Lee K, Mathes SJ. Endoscopic subcondylar fracture repair: functional, aesthetic, and radiographic outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998; 102:1434–1443. discussion 1444-5PMID: 9773997.

Article4. Loukota RA. Endoscopically assisted reduction and fixation of condylar neck/base fractures--The learning curve. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006; 44:480–481. PMID: 16423433.

Article5. Salgarelli AC, Anesi A, Bellini P, Pollastri G, Tanza D, Barberini S, et al. How to improve retromandibular transmasseteric anteroparotid approach for mandibular condylar fractures: our clinical experience. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013; 42:464–469. PMID: 23395651.

Article6. Manisali M, Amin M, Aghabeigi B, Newman L. Retromandibular approach to the mandibular condyle: a clinical and cadaveric study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003; 32:253–256. PMID: 12767870.

Article7. Widmark G, Bågenholm T, Kahnberg KE, Lindahl L. Open reduction of subcondylar fractures. A study of functional rehabilitation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996; 25:107–111. PMID: 8727580.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Transmasseteric Approach for Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of Mandible Subcondylar Fracture

- Modified high-submandibular appraoch for open reduction and internal fixation of condylar fracture: case series report

- New protocol for simplified reduction and fixation of subcondylar fractures of the mandible: a technical note

- Complications of the retromandibular transparotid approach for low condylar neck and subcondylar fractures: a retrospective study

- Retromandibular approach for open reduction & internal fixation of mandibular condylar neck fracture