Diagnostic Utility of Osteocalcin, Undercarboxylated Osteocalcin, and Alkaline Phosphatase for Osteoporosis in Premenopausal and Postmenopausal Women

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Medical Biochemistry, Haydarpasa Numune Teaching and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey. sacideata@yahoo.com

- 2Department of Medical Biochemistry, Acibadem Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

- 3Department of Medical Biochemistry, Iskenderun Military Hospital, Iskenderun, Hatay, Turkey.

- 4Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation, Haydarpasa Numune Teaching and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

- 5Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Haydarpasa Numune Teaching and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

- KMID: 1781434

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3343/alm.2012.32.1.23

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

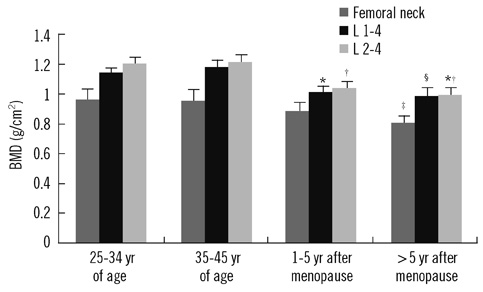

We aimed to investigate the diagnostic utility of osteocalcin (OC), undercarboxylated osteocalcin (ucOC), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in pre- and postmenopausal women for femoral neck, L1-4, and L2-4 bone mineral density (BMD) values by taking into consideration their age, body mass index (BMI), and menopausal status.

METHODS

Premenopausal (N=40) and postmenopausal cases (N=42) were classified as 25-34 or 35-45 yr of age and within the first 5 yr or 5 yr or more after the onset of menopause, respectively.

RESULTS

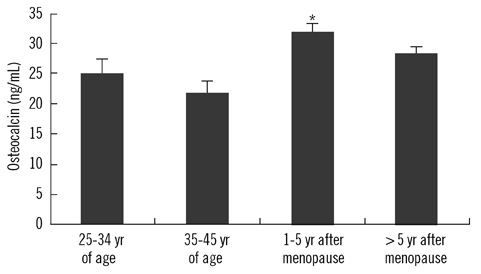

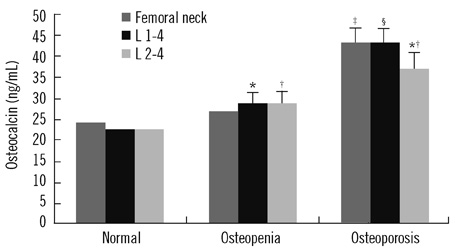

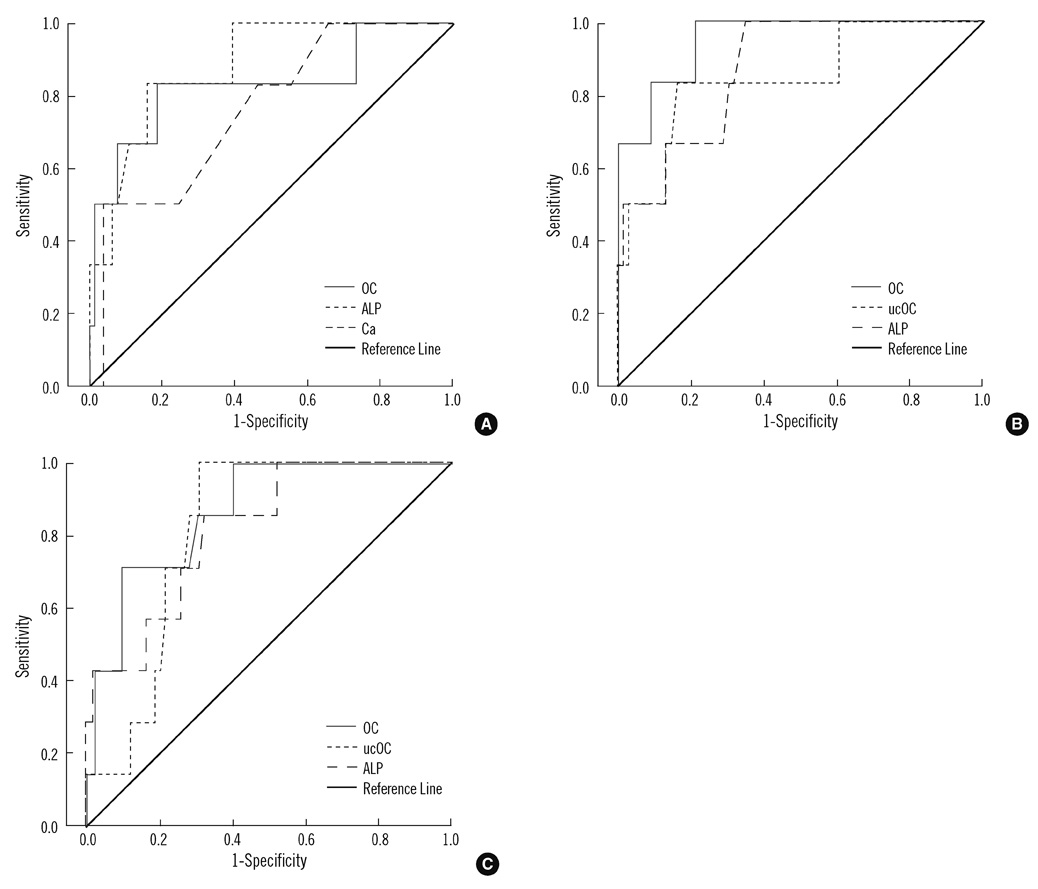

Among the groups, statistical differences were found for age, BMI, OC, ucOC, ALP, femoral neck BMD, L1-4 BMD, and L2-4 BMD. The highest serum OC, ucOC, and ALP levels were observed in cases within the first 5 yr after the onset of menopause, probably due to a more rapid bone turnover rate. The best predictors for the femoral neck osteoporosis were ALP, OC, and calcium (areas under the ROC curve [AUC]=0.882, 0.829, and 0.761, respectively), and those for L1-4 and L2-4 osteoporosis were OC, ALP, and ucOC (AUC=0.949, 0.873, and 0.845; and 0.866, 0.819, and 0.814, respectively). Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that the most discriminative parameter for osteoporosis was OC.

CONCLUSIONS

These results indicate that serum OC levels, with or without ucOC and ALP, may be useful to monitor follow-up changes that currently cannot be assessed with BMD and to diagnose femoral neck, L1-4 spine, and L2-4 spine osteoporosis.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 4 articles

-

Association between Serum Osteocalcin Levels and Metabolic Syndrome according to the Menopausal Status of Korean Women

Jin-Sook Moon, Mi Hyeon Jin, Hyun-Min Koh

J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(8):e56. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e56.Association of Serum Osteocalcin with Insulin Resistance and Coronary Atherosclerosis

Jee-Hyun Kang

J Bone Metab. 2016;23(4):183-190. doi: 10.11005/jbm.2016.23.4.183.Dietary behaviors and nutritional status according to the bone mineral density status among adult female North Korean refugees in South Korea

Su-Hyeon Kim, Soo-Kyung Lee, Sin-Gon Kim

J Nutr Health. 2019;52(5):449-464. doi: 10.4163/jnh.2019.52.5.449.Osteocalcin: Beyond Bones

Jakub Krzysztof Nowicki, Elżbieta Jakubowska-Pietkiewicz

Endocrinol Metab. 2024;39(3):399-406. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2023.1895.

Reference

-

1. NIH consensus development panel on osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy, March 7-29, 2000: highlights of the conference. South Med J. 2001. 94:569–573.2. Garnero P, Sornay-Rendu E, Chapuy MC, Delmas PD. Increased bone turnover in late postmenopausal women is a major determinant of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 1996. 3:337–349.

Article3. Christiansen C, Lindsay R. Estrogens, bone loss and preservation. Osteoporos Int. 1990. 1:7–13.

Article4. Dalle Carbonare L, Giannini S. Bone microarchitecture as an important determinant of bone strength. J Endocrinol Invest. 2004. 27:99–105.

Article5. Kanis JA. Diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk. Lancet. 2002. 359:1929–1936.

Article6. Sinaki M. Braddom RL, editor. Prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2006. 3rd ed. Elsevier, Philadelphia: Elsevier;926–949.7. Garnero P, Delmas PD. Biochemical markers of bone turnover. Applications for osteoporosis. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1998. 27:303–323.8. Allison JL, Stephen H, Richard E. Measurement of osteocalcin. Ann Clin Biochem. 2000. 37:432–446.

Article9. Swaminathan R. Biochemical markers of bone turnover. Clin Chim Acta. 2001. 313:95–105.

Article10. Aonuma H, Miyakoshi N, Hongo M, Kasukawa Y, Shimada Y. Low serum levels of undercarboxylated osteocalcin in postmenopausal osteoporotic women receiving an inhibitor of bone resorption. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2009. 218:201–205.

Article11. Vergnaud P, Garnero P, Meunier PJ, Bréart G, Kamihagi K, Delmas PD. Undercarboxylated osteocalcin measured with a specific immunoassay predicts hip fracture in eldery women: the EPIDOS study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997. 82:719–724.12. Booth SL, Broe KE, Gagnon DR, Tucker KL, Hannan MT, McLean RR, et al. Vitamin K intake and bone mineral density in women and men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003. 77:512–516.

Article13. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO study group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1994. 943:1–129.14. Sokoll LJ, O'Brien ME, Camilo ME, Sadowski JA. Undercarboxylated osteocalcin and development of a method to determine vitamin K status. Clin Chem. 1995. 41:1121–1128.

Article15. Chailurkit LO, Ongphiphadhanakul B, Piaseu N, Saetung S, Rajatanavin R. Biochemical markers of bone turnover and response of bone mineral density to intervention in early postmenopausal women: an experience in a clinical laboratory. Clin Chem. 2001. 47:1083–1088.

Article16. Ivaska KK, Hentunen TA, Vääräniemi J, Ylipahkala H, Pettersson K, Vääräniemi HK. Release of intact and fragmented osteocalcin molecules from bone matrix during bone resorption in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2004. 279:18361–18369.

Article17. Lindsay R. The menopause and osteoporosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1996. 87:S2. S16–S19.

Article18. Gnudi S, Mongiorgi R, Figus E, Bertocchi G. Evaluation of the relative rates of bone mineral content loss in postmenopause due to both estrogen deficiency and ageing. Boll Soc Ital Biol Sper. 1990. 66:1153–1159.19. Plantalech L, Guillaumont M, Vergnaud P, Leclercq M, Delmas PD. Impairment of gamma carboxylation of circulating osteocalcin (bone gla protein) in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res. 1991. 6:1211–1216.

Article20. Szulc P, Chapuy MC, Meunier PJ, Delmas PD. Serum undercarboxylated osteocalcin is a marker of the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. J Clin Invest. 1993. 91:1769–1774.

Article21. Knapen MH, Nieuwenhuijzen Kruseman AC, Wouters RS, Vermeer C. Correlation of serum osteocalcin fractions with bone mineral density in women during the first 10 yr after menopause. Calcif Tissue Int. 1998. 63:375–379.22. Yasui T, Uemura H, Tomita J, Miyatani Y, Yamada M, Miura M, et al. Association of serum undercarboxylated osteocalcin with serum estradiol in pre-, peri- and early post-menopausal women. J Endocrinol Invest. 2006. 29:913–918.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Effects of Hormon Replacement Therapy on Serum Osteocalcin, Serum Calcium, Serum Alkaline Phosphatase, and Urine Calcium of Postmenopausal Women

- Evaluation of Osteoporosis Using the Biochemical Markers

- Relationship among Estradiol, Lipid Profile, Biochemical Markers, and Bone Mineral Density according to Postmenopausal Period

- Study on Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphisms of Vitamin - D Receptor Gene in relation to Bone Mineral Density and Bone Markers in Pre - and Postmenopausal Korean Women

- The pattern of urinary deoxypyridinoline and serum osteocalcin across menopausal transition in women