Yonsei Med J.

2010 Nov;51(6):895-900. 10.3349/ymj.2010.51.6.895.

Clinical Predictors of Novel Influenza A (H1N1) Infection in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Family Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. indi5645@yuhs.ac

- 2Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Internal Medicine and AIDS Research Institute, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 1779637

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2010.51.6.895

Abstract

- PURPOSE

Pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus has spread rapidly and prompt diagnosis is needed for successful treatment and prevention of transmission. We investigated clinical predictors, validated the use of previous criteria with laboratory tests, and evaluated the clinical criteria for H1N1 infection in the Korean population.

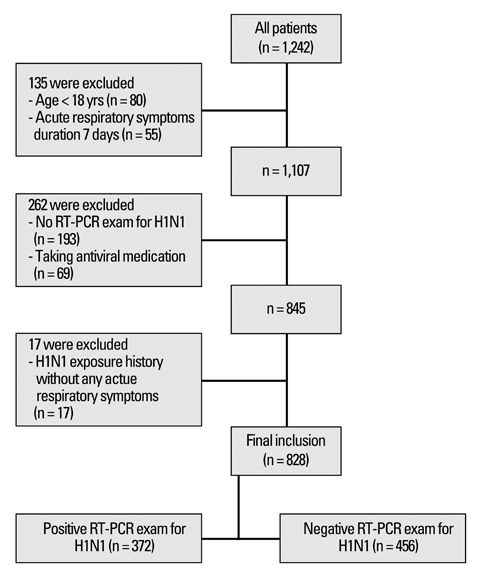

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We analyzed clinical and laboratory evaluation data from outpatient clinics at Severance Hospital in Seoul, Korea between November 11 and December 5, 2009.

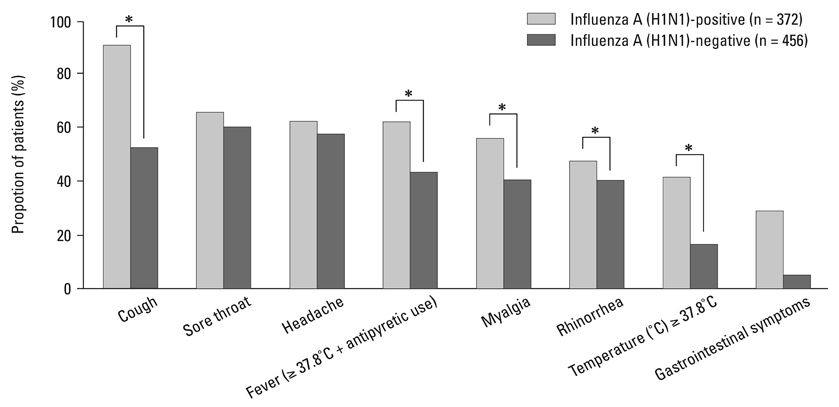

RESULTS

This analysis included a total of 828 patients. Of these, 372 (44.9%) patients were confirmed with H1N1 infection by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The most common and predictive symptom was cough (90.3%, OR 8.87, 95% CI 5.89-13.38) and about 40% of H1N1-positive patients were afebrile. The best predictive model of H1N1 infection was cough plus fever or myalgia. The sensitivities, specificities, positive predictive values, and negative predictive values of our suggested criteria were 73.9%, 69.5%, 66.4%, and 76.6%, respectively.

CONCLUSION

Cough was the most common independent symptom in patients with laboratory-confirmed H1N1 infection, and while not perfect, the combination of cough plus fever or myalgia is suggested as clinical diagnostic criteria. Health care providers in Korea should suspect a cough without fever to be an early symptom of H1N1 infection.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Characteristics of Outpatients with Pandemic H1N1/09 Influenza in a Tertiary Care University Hospital in Korea

Kyung Sun Park, Tae Sung Park, Jin Tae Suh, You Sun Nam, Mi Suk Lee, Hee Joo Lee

Yonsei Med J. 2012;53(1):213-220. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2012.53.1.213.

Reference

-

1. Carrat F, Tachet A, Rouzioux C, Housset B, Valleron AJ. Evaluation of clinical case definitions of influenza: detailed investigation of patients during the 1995-1996 epidemic in France. Clin Infect Dis. 1999. 28:283–290.

Article2. Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Investigation Team. Dawood FS, Jain S, Finelli L, Shaw MW, Lindstrom S, et al. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med. 2009. 360:2605–2615.

Article3. Sym D, Patel PN, El-Chaar GM. Seasonal, avian, and novel H1N1 influenza: prevention and treatment modalities. Ann Pharmacother. 2009. 43:2001–2011.

Article4. Call SA, Vollenweider MA, Hornung CA, Simel DL, McKinney WP. Does this patient have influenza? JAMA. 2005. 293:987–997.

Article5. Jain R, Goldman RD. Novel influenza A(H1N1): clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009. 25:791–796.6. Monto AS, Gravenstein S, Elliott M, Colopy M, Schweinle J. Clinical signs and symptoms predicting influenza infection. Arch Internal Med. 2000. 160:3243–3247.

Article7. Boivin G, Hardy I, Tellier G, Maziade J. Predicting influenza infections during epidemics with use of a clinical case definition. Clin Infect Dis. 2000. 31:1166–1169.

Article8. Gerrard J, Keijzers G, Zhang P, Vossen C, Macbeth D. Clinical diagnostic criteria for isolating patients admitted to hospital with suspected pandemic influenza. Lancet. 2009. 374:1673.

Article9. Bellei N, Carraro E, Perosa A, Watanabe A, Arruda E, Granato C. Acute respiratory infection and influenza-like illness viral etiologies in Brazilian adults. J Med Virol. 2008. 80:1824–1827.

Article10. Navarro-Marí JM, Pérez-Ruiz M, Cantudo-Muñoz P, Petit-Gancedo C, Jiménez-Valera M, Rosa-Fraile M. Influenza Surveillance Network in Andalusia, Spain. Influenza-like illness criteria were poorly related to laboratory-confirmed influenza in a sentinel surveillance study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005. 58:275–279.11. Ong AK, Chen MI, Lin L, Tan AS, Nwe NW, Barkham T, et al. Improving the clinical diagnosis of influenza--a comparative analysis of new influenza A (H1N1) cases. PloS One. 2009. 4:e8453.12. Interim guidance for infection control for care of patients with confirmed or suspected novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in a healthcare setting. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed November 30, 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/guidelines_infection_control.htm.13. Diagnosis and Treatment of Influenza A (H1N1). Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed December 2, 2009. http://flu.cdc.go.kr.14. World Health Organization. Human infection with pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus: updated interim WHO guidance on global surveillance. 2009.15. Lorusso A, Faaberg KS, Killian ML, Koster L, Vincent AL. One-step real-time RT-PCR for pandemic influenza A virus (H1N1) 2009 matrix gene detection in swine samples. J Virol Methods. 2010. 164:83–87.

Article16. Chang LY, Shih SR, Shao PL, Huang DT, Huang LM. Novel swine-origin influenza virus A (H1N1): the first pandemic of the 21st century. J Formos Med Assoc. 2009. 108:526–532.17. Vaillant L, La Ruche G, Tarantola A, Barboza P. epidemic intelligence team at InVS. Epidemiology of fatal cases associated with pandemic H1N1 influenza 2009. Euro Surveill. 2009. 14:pii: 19309.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Influenza Associated Pneumonia

- Encephalitis Induced by 2009 H1N1 Influenza A

- Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and management of pandemic novel Influenza A (H1N1)

- Pandemic Influenza (H1N1) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis Co-infection

- A Case of Novel Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Pneumonia Complicated Pnemomediastinum and Subcutenous Emphysema