Yonsei Med J.

2009 Aug;50(4):482-492. 10.3349/ymj.2009.50.4.482.

Trends in Educational Differentials in Suicide Mortality between 1993 - 2006 in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Preventive Medicine, College of Medicine, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, Korea. hyp026@cau.ac.kr

- 2Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Division of Mathematical Sciences, Pukyong National University, Busan, Korea.

- 4Oral Health Promotion Supporting Committee, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, Seoul, Korea.

- 5Department of Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine, Kangwon National University, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 1758606

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2009.50.4.482

Abstract

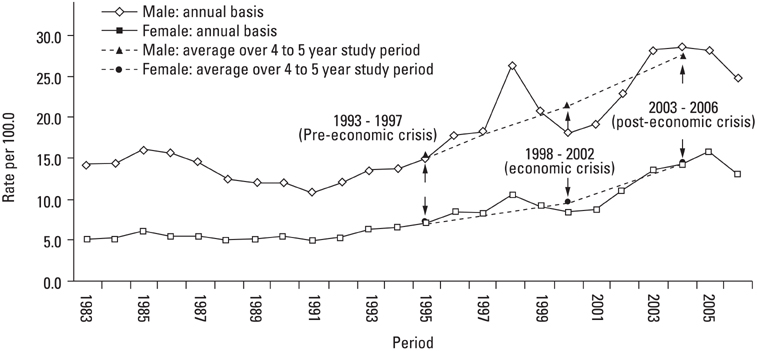

- PURPOSE

This study aims to examine how inequalities in suicide by education changed during and after macroeconomic restructuring following the economic crisis of 1997 in South Korea. MATERIALS AND METHODS: Using Korea's 1995, 2000, and 2005 census data aggregately linked to mortality data (1993 - 2006), relative and absolute differentials in suicide mortality by education were calculated by gender and age among Korean population aged 35 and over. RESULTS: Average annual suicide mortality rates have steadily increased from 1993 - 1997 to 2003 - 2006 in almost all sociodemographic groups stratified by gender, age, and education. Based on the relative index of inequality (RII) and slope index of inequality (SII), educational differentials in suicide mortality generally increased over time in men and women aged 45 years +. Although RII did not increase with year among men and women aged 35 - 44 years, SII showed a significantly increasing trend in this age group. CONCLUSION: These worsening absolute inequalities in suicide mortality indicate that the governmental suicide prevention policy should be directed toward socially disadvantaged groups of the Korean population.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Socioeconomic inequalities in health status in Korea

Kyunghee Jung-Choi, Yu-Mi Kim

J Korean Med Assoc. 2013;56(3):167-174. doi: 10.5124/jkma.2013.56.3.167.

Reference

-

1. Shin JS, Chang HJ. Economic reform after the financial crisis: a critical assessment of institutional transition and transition costs in South Korea. Review of International Political Economy. 2005. 12:409–433.

Article2. Pirie I. Economic crisis and the construction of a neo-liberal regulatory regime in Korea. Competition Change. 2006. 10:49–71.

Article3. Mah JS. Economic restructuring in post-crisis Korea. Journal of Socio-Economic. 2006. 35:682–690.

Article4. Crotty J, Lee KK. A political-economic analysis of the failure of neo-liberal restructuring in post-crisis Korea. Cambridge Journal of Economics. 2002. 26:667.

Article5. Lim HC, Jang JH. Neo-liberalism in post-crisis South Korea: Social conditions and outcomes. Journal of Contemporary Asia. 2006. 36:442–463.

Article6. Office KNS. Korean Statistical Information System In.7. Leon DA, Chenet L, Shkolnikov VM, Zakharov S, Shapiro J, Rakhmanova G, et al. Huge variation in Russian mortality rates 1984-94: artefact, alcohol, or what? Lancet. 1997. 350:383–388.8. Shkolnikov V, McKee M, Leon DA. Changes in life expectancy in Russia in the mid-1990s. Lancet. 2001. 357:917–921.9. Men T, Brennan P, Boffetta P, Zaridze D. Russian mortality trends for 1991-2001: analysis by cause and region. BMJ. 2003. 327:964.

Article10. Tapia Granados JA. Increasing mortality during the expansions of the US economy, 1900-1996. Int J Epidemiol. 2005. 34:1194–1202.

Article11. Abe R, Shioiri T, Nishimura A, Nushida H, Ueno Y, Kojima M, et al. Economic slump and suicide method: preliminary study in Kobe. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004. 58:213–216.

Article12. Weyerer S, Wiedenmann A. Economic factors and the rates of suicide in Germany between 1881 and 1989. Psychol Rep. 1995. 76:1331–1341.

Article13. Leenaars AA, Yang B, Lester D. The effect of domestic and economic stress on suicide rates in Canada and the United States. J Clin Psychol. 1993. 49:918–921.

Article14. Morrell S, Taylor R, Quine S, Kerr C. Suicide and unemployment in Australia 1907-1990. Soc Sci Med. 1993. 36:749–756.

Article15. Hintikka J, Saarinen PI, Viinamäki H. Suicide mortality in Finland during an economic cycle, 1985-1995. Scand J Public Health. 1999. 27:85–88.

Article16. Park JS, Lee JY, Kim SD. A study for effects of economic growth rate and unemployement rate to suicide rate in Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2003. 36:85–91.17. Kim H, Song YJ, Yi JJ, Chung WJ, Nam CM. Changes in mortality after the recent economic crisis in South Korea. Ann Epidemiol. 2004. 14:442–446.

Article18. Khang YH, Lynch JW, Kaplan GA. Impact of economic crisis on cause-specific mortality in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2005. 34:1291–1301.

Article19. Joint OECD/Korea Regional Centre on Health and Social Policy MoHWaFA, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Health at a Glance 2007 OECD Indicators. 2008. Seoul:20. Koreans' healthcare status quo based on major indexes of OECD Health Data 2008. Affairs MoHWaF. 2008. Available from:http://stat.mw.go.kr/homepage/data/oversea_data_content.jsp?menu_id=24&curr_page=1&ctrl_command=doNothing&seq_no=193.21. Stack S. Suicide: a 15-year review of the sociological literature. Part I: cultural and economic factors. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2000. 30:145–162.22. Stack S. Suicide: a 15-year review of the sociological literature. Part II: modernization and social integration perspectives. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2000. 30:163–176.23. Khang YH, Lynch JW, Kaplan GA. Health inequalities in Korea: age- and sex-specific educational differences in the 10 leading causes of death. Int J Epidemiol. 2004. 33:299–308.

Article24. Oh JK, Cho Y, Kim CY. Socio-Demographic characteristics of suicides in South Korea. Health Soc Sci. 2005. 18:191–210.25. Park JY, Moon KT, Chae YM, Jung SH. [Effect of sociodemographic factors, cancer, psychiatric disorder on suicide: gender and age-specific patterns.]. J Prev Med Public Health. 2008. 41:51–60.

Article26. Kim MD, Hong SC, Lee SY, Kwak YS, Lee CI, Hwang SW, et al. Suicide risk in relation to social class: a national register-based study of adult suicides in Korea, 1999-2001. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2006. 52:138–151.

Article27. Cho HJ, Khang YH, Yang S, Harper S, Lynch JW. Socioeconomic differentials in cause-specific mortality among South Korean adolescents. Int J Epidemiol. 2007. 36:50–57.

Article28. Khang YH, Yun SC, Hwang IA, Lee MS, Lee SI, Jo MW, et al. [Changes in mortality inequality in relation to the South Korean economic crisis: use of area-based socioeconomic position.]. J Prev Med Public Health. 2005. 38:359–365.29. Blakely TA, Collings SC, Atkinson J. Unemployment and suicide. Evidence for a causal association? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003. 57:594–600.

Article30. Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE. Measuring the magnitude of socioeconomic inequalities in health: an overview of available measures illustrated with two examples from Europe. Soc Sci Med. 1997. 44:757–771.

Article31. Harper S, Lynch JW. Oakes JM, Kaufman JS, editors. Measuring health inequalities. Methods in social epidemiology. 2006. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bassj;134–168.32. Leite ML, Nicolosi A, Osella AR, Molinari S, Cozzolino E, Velati C, et al. Modeling incidence rate ratio and rate difference: additivity or multiplicativity of human immunodeficiency virus parenteral and sexual transmission among intravenous drug users. Northern Italy Seronegative Drug Addicts Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1995. 141:16–24.

Article33. Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005. 162:199–200.

Article34. Fukuda Y, Nakamura K, Takano T. Cause-specific mortality differences across socioeconomic position of municipalities in Japan, 1973-1977 and 1993-1998: increased importance of injury and suicide in inequality for ages under 75. Int J Epidemiol. 2005. 34:100–109.

Article35. Cubbin C, LeClere FB, Smith GS. Socioeconomic status and the occurrence of fatal and nonfatal injury in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2000. 90:70–77.

Article36. Lorant V, Kunst AE, Huisman M, Costa G, Mackenbach J. EU Working Group on Socio-Economic Inequalities in Health. Socio-economic inequalities in suicide: a European comparative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005. 187:49–54.

Article37. Valkonen T, Martelin T. Occupational class and suicide: an example of the elaboration of a relationship. 1998. Helsinki: University of Helsinki, Department of Sociology;Research Reports No. 222.38. Shkolnikov VM, Deev AD, Kravdal O, Valkonen T. Educational diffentials in male mortality in Russia and Northern Europe. A comparison of an epidemiological cohort from Moscow and St. Petersburg with the male populations of Helsinki and Oslo. Demographia Research. 2004. 10:1–25.39. Khang YH, Kim HR. Relationship of education, occupation, and income with mortality in a representative longitudinal study of South Korea. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005. 20:217–220.

Article40. Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Davey Smith G. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006. 60:7–12.

Article41. Howard KI, Cornille TA, Lyons JS, Vessey JT, Lueger RJ, Saunders SM. Patterns of mental health service utilization. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996. 53:696–703.

Article42. Mäki NE, Martikainen PT. The effects of education, social class and income on non-alcohol- and alcohol-associated suicide mortality: a register-based study of finnish men aged 25-64. Eur J Population. 2008. 24:385–404.

Article43. Park CG. Consumer credit market in Korea since the economic crisis. Financial sector development in the Pacific Rim, East Asia seminar on Economics. 2007. 18. Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Inc;NBER chapters series 0412.

Article44. Oh S. Personal bankruptcy in Korea: Challenges and responses. theoretical inquiries in Law. 2006. 7(2):Article 12. Available from http://www.bepress.com/til/default/vol7/iss2/art12.

Article45. Kim YS. The cause of nonstandard workforce increase. Socio-Economic Review. 2003. 21:289–326.46. Kim IH, Khang YH, Muntaner C, Chun H, Cho SI. Gender, precarious work, and chronic diseases in South Korea. Am J Ind Med. 2008. 51:748–757.

Article47. Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Pamuk ER, Cohen RD, Heck KE, Balfour JL, et al. Income inequality and mortality in metropolitan areas of the United States. Am J Public Health. 1998. 88:1074–1080.

Article48. Fernquist RM. Perceived income inequality and suicide rates in Central/Eastern European countries and Western countries, 1990-1993. Death Stud. 2003. 27:63–80.

Article49. Unnithan NP, Whitt H. Inequality, economic development and lethal violence: a cross-national analysis of suicide and homicide. International Journal of Comparative Sociology. 1992. 33:182–196.

Article50. Kposowa AJ. Marital status and suicide in the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000. 54:254–261.

Article51. Blumenthal SJ. Suicide: a guide to risk factors, assessment, and treatment of suicidal patients. Med Clin North Am. 1988. 72:937–971.

Article52. Suh TW. Current situation and trends of suicidal deaths, ideas and attempts in Korea. Health Soc Welfare Rev. 2001. 21:106–125.53. Lorant V, Kunst AE, Huisman M, Bopp M, Mackenbach J. EU Working Group. A European comparative study of marital status and socio-economic inequalities in suicide. Soc Sci Med. 2005. 60:2431–2441.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Study on Regional Differentials in Death Caused by Suicide in South Korea

- Secular Trends of Suicide Mortality in Korea

- Analysis of suicide statistics and trends between 2011 and 2021 among Korean women

- Trends in Prevalence and the Differentials of Unhealthy Dietary Habits by Maternal Education Level among Korean Adolescents

- Difference of Spatiotemporal Patterns of Suicide Between Genders in Korea Over a Decade Using Geographic Information Systems