Korean J Women Health Nurs.

2023 Dec;29(4):348-356. 10.4069/kjwhn.2023.12.14.1.

Analysis of suicide statistics and trends between 2011 and 2021 among Korean women

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Nursing, Catholic KkottongnaeUniversity, Cheongju, Korea

- 2Statistical Research Institute, Statistics Korea, Daejeon, Korea

- 3Vital Statistics Division, Statistics Korea, Daejeon, Korea

- 4College of Nursing & Research Institute of Nursing Innovation, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea

- KMID: 2550998

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2023.12.14.1

Abstract

- Purpose

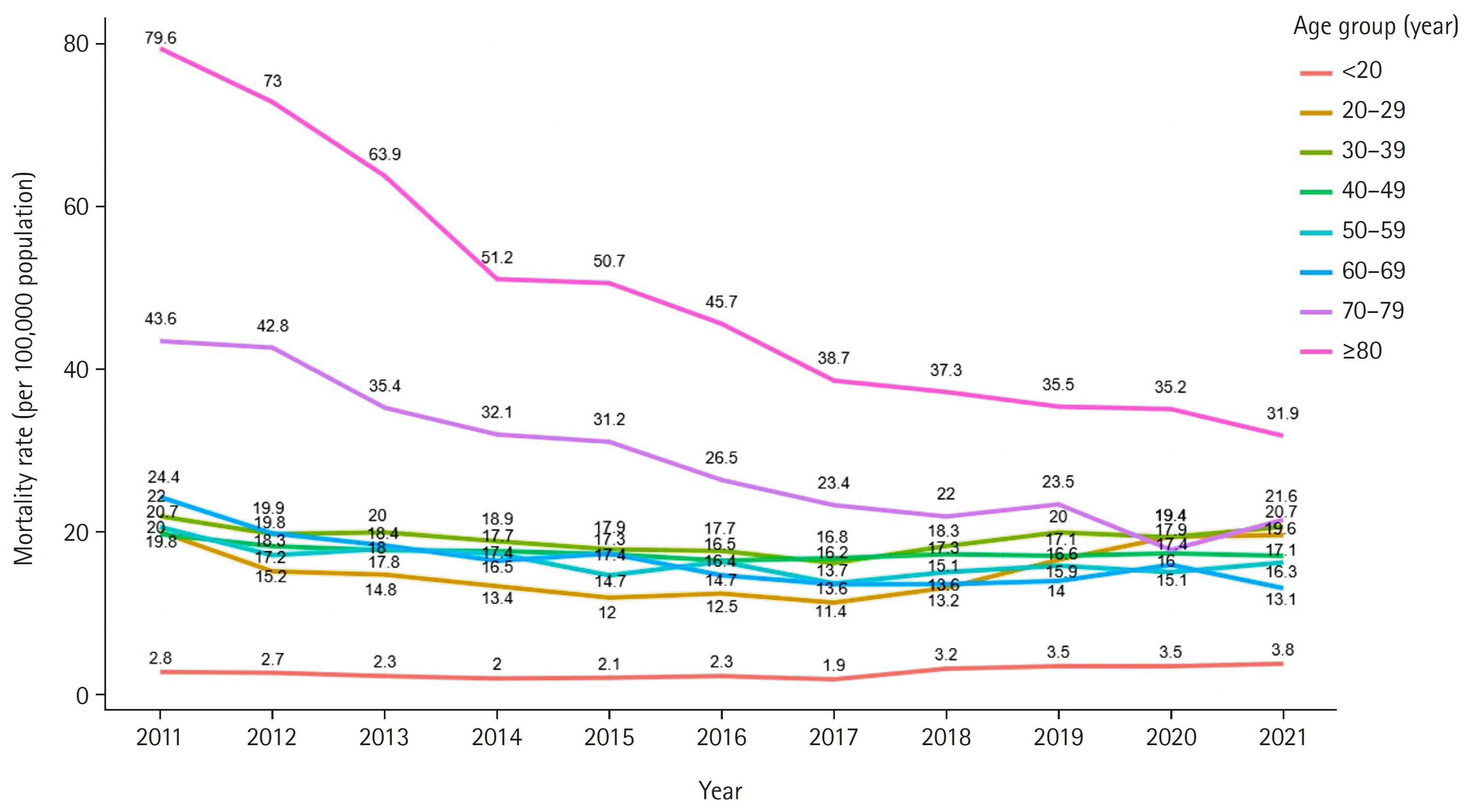

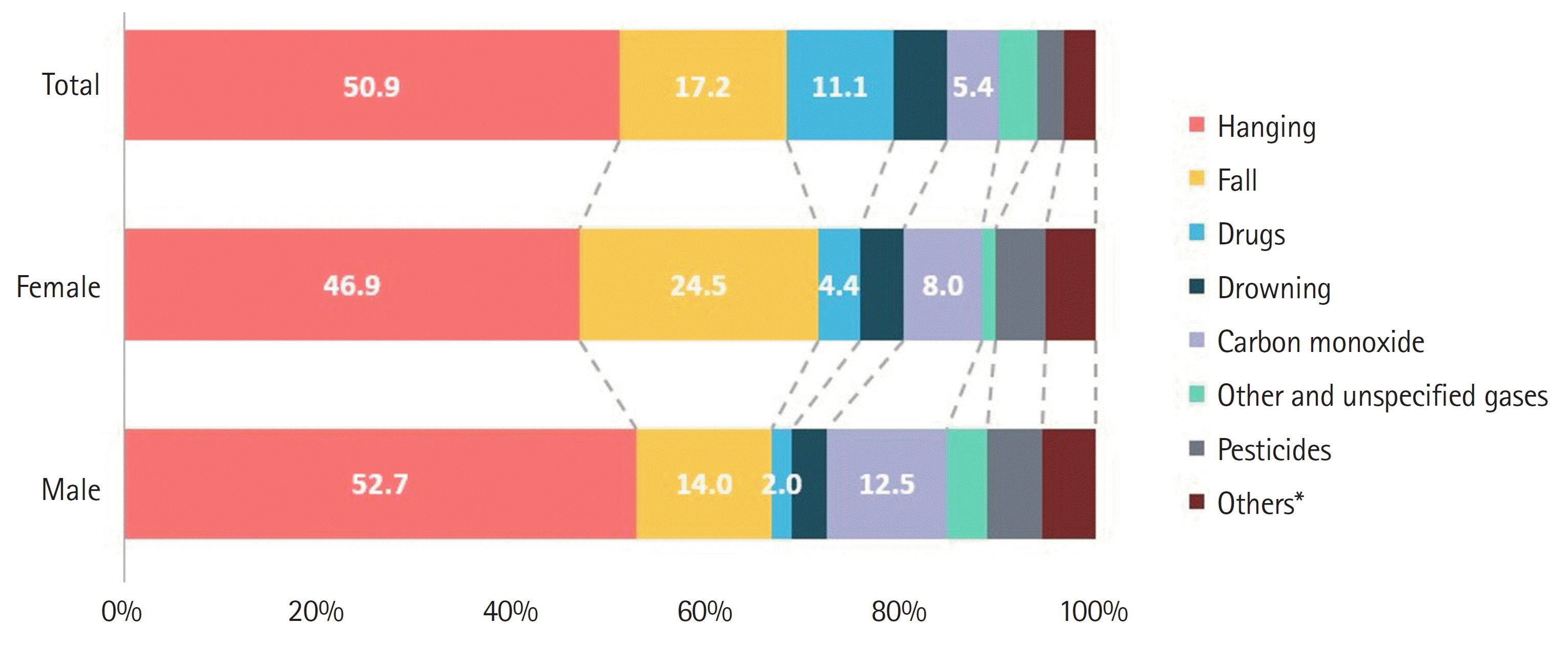

This study aims to analyze the number of suicide deaths in women, trends in suicide mortality, characteristics of suicide by age, and outcomes of suicide means over the past decade (2011– 2021) in South Korea. Methods: Using cause of death data from Statistics Korea, an in-depth analysis of Korean women’s suicide trends was conducted for the period of 2011–2021. Results: In 2021, women’s suicide death in Korea was 4,159, a rate of 16.2 per 100,000 population. The rate increased by 1.4% from the previous year. Since 2011, women’s suicide rate has been on a steady downward trend, but since 2018, it has been on the rise again. Suicide rates among women in their 20s and 30s have increased, especially since the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, and suicide rates among women over 70 years remain high. As compared to 2011, pesticide poisoning and hanging among the means of suicide have decreased significantly, while drug and carbon monoxide continue to increase. Conclusion: Suicide rates for Korean women in their 20s and 30s have increased significantly in recent years, and those for women over 70 years remain high. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the causes and establish national policies for targeted management of these age groups, which contributes significantly to the rising suicide rate among Korean women.

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Statistics Korea. 2021 Cause of death statistics [Internet]. Daejeon: Author;2021. [cited 2022 Sep 26]. Available from: https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301060200&bid=218&act=view&list_no=420715.2. Statistics Korea. 2022 Safety report [Internet]. Daejeon: Author;2021. [cited 2023 Apr 28]. Available from: https://kostat.go.kr/synap/skin/doc.html?fn=489b4f036197727d96087b6b319d6664f550bf8d2c78c651caac201db0c576d8&rs=/synap/preview/board/246/.3. Kim JS, Kim JE, Song IH. 2017 Suicide prevention policies of metropolitan local governments in Korea: analysis of core components and detailed plans based on the 3rd national suicide prevention master plan and the local government suicide prevention plan. Health Soc Welf Rev. 2018; 38(3):580–610. https://doi.org/10.15709/hswr.2018.38.3.580.

Article4. Korean Statistical Information Service. Suicide rate per 100,000 (OECD member countries) [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2023. [cited 2023 Dec 13]. Available from: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_2KAAD33_OECD&vw_cd=MT_RTITLE&list_id=UTIT_OECD_B&scrId=&seqNo=&lang_mode=ko&obj_var_id=&itm_id=&conn_path=MT_RTITLE&path=%252FstatisticsList%252FstatisticsListIndex.do.5. Han MH. Identification of high-risk group of suicide attempt according to suicidal thinking. J Korea Acad-Ind Coop Soc. 2023; 24(4):382–393. https://doi.org/10.5762/KAIS.2023.24.4.382.

Article6. Lee SW. A longitudinal study on predictors of suicide ideation in old people: using a panel logit model. Health Soc Welf Rev. 2017; 37(3):191–229. https://doi.org/10.15709/hswr.2017.37.3.191.

Article7. Jeon JA. Gender differences in mental health of Korean adults: focusing on depression. Health Welf Policy Forum. 2014; (210):17–26.8. MicroData Integrated Service. The census of population trend: annual data of female mortality by sex and age, and female mortality by means of suicide [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2022. [cited 2022 Sep 26]. Available from: https://mdis.kostat.go.kr/dwnlSvc/ofrSurvSearch.do?curMenuNo=UI_POR_P9240.9. The Economist. South Korea’s suicide rate fell for years. Women are driving it up again [Internet]. London: Author;2023 May 22. [cited 2023 May 22]. Available from: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2023/05/22/south-koreas-suicide-rate-fell-for-years-women-are-driving-it-up-again.10. Statistics Korea. Economically active population survey [Internet]. Daejeon: Author;2022. [cited 2022 Oct 25]. Available from: https://www.kostat.go.kr/synap/skin/doc.html?fn=456c6164a33838ee49efd2f270caf9bd53ce30a650451b99365e862222179412&rs=/synap/preview/board/210/.11. Jung KY. Is the working environment of female workers safe? Seoul: Korean Confederation of Trade Unions Policy Research Institute;2019. Aug. 20. p. 22. Issue paper No.: 2019-05.12. Choi J, Noh S, Jeong H, Kim H. The multilevel factors related to the depression symptoms of married middle-aged working women. Korean J Health Educ Promot. 2023; 40(2):67–78. http://doi.org/10.14367/kjhep.2023.40.2.67.

Article13. Ko EJ. A study on the system reinforcement plan to complement the vulnerability of women’s employment due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Legislation. 2021; 695:41–66.14. Lee JM, Kim TW. A study on the causes of poverty in the elderly: focusing on labor market experiences and changes in family structure. Health Soc Welf Rev. 2020; 40(2):193–221. https://doi.org/10.15709/hswr.2020.40.2.193.

Article15. Lee HK. A study on the relationship between grief level and suicidal ideation among the bereaved elderly who are living alone: focusing on the mediating effects of depression. Mental Health Soc Work. 2016; 44(1):24–47.16. Kim NS, Kim MH, Kim S, Kim Y, Kim JW, Park E, et al. Women’s health statistics (4th) and primary health issue analysis. Sejong: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs;2020. p. 751. Report No.: 11-1790399-000018-01.17. Statistics Korea. 2021 Elderly statistics [Internet]. Daejeon: Author;2021. [cited 2023 Oct 30]. Available from: https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301010000&bid=10820&act=view&list_no=403253&tag=&nPage=1&ref_bid=203,204,205,206,207,210,211,11109,11113,11814,213,215,214,11860,11695,216,218,219,220,10820,11815,11895,11816,208,245,222,223,225,&keyField=T&keyWord=%EA%B3%A0%EB%A0%B9%EC%9E%90%20%ED%86%B5%EA%B3%84&bodo_b_type=all.18. Nam HJ, Jang EH, Hong SH. A systematic review on suicide of the elderly people living alone. Korean J Gerontol Soc Welf. 2021; 76(2):91–130. https://doi.org/10.21194/kjgsw.76.2.202106.91.

Article19. Lee G, Yang SJ, Woo E. Past, present, and future of home visiting healthcare services based on public health centers in Korea. J Korean Public Health Nurs. 2018; 32(1):5–18. https://doi.org/10.5932/JKPHN.2018.32.1.5.

Article20. Statistics Korea. Current smoking rate [Internet]. Daejeon: Author;2023. [cited 2023 Nov 07]. Available from: https://www.index.go.kr/unify/idx-info.do?idxCd=4237.21. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Korea national health & nutrition examination survey fact sheet [Internet]. Cheongju: Author;2020. [cited 2023 Nov 07]. Available from: https://knhanes.kdca.go.kr/knhanes/sub04/sub04_04_05.do.22. Korean Women’s Development Institute. Monthly alcohol consumption rate (by gender/age) [Internet]. Seoul: Author;2023. [cited 2023 Oct 30]. Available from: https://gsis.kwdi.re.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=338&tblId=DT_LCD_B001.23. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. An in-depth report on drinking based on the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [Internet]. Cheongju: Author;2023. [cited 2023 Oct 30]. Available from: https://knhanes.kdca.go.kr/knhanes/sub04/sub04_04_02.do.24. Kim HS, Kim Y, Cho YH. Combined influence of smoking and alcohol drinking on suicidal ideation and attempts among Korean adults: using data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008~2011. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2016; 28(6):609–618. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2016.28.6.609.

Article25. Jee SH, Kivimaki M, Kang HC, Park IS, Samet JM, Batty GD. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in relation to suicide mortality in Asia: prospective cohort study of over one million Korean men and women. Eur Heart J. 2011; 32(22):2773–2780. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehr229.

Article26. Policy Briefing of Republic of Korea. Policy news: Creation of 780,000 “women’s jobs” in digital, care, and disease prevention, etc. [Internet]. Sejong: Ministry of Gender Equality and Family;2021. Mar. 4. [cited 2023 Oct 30]. Available from: https://www.korea.kr/news/policyNewsView.do?newsId=148884618.27. Policy Briefing of Republic of Korea. “Tailored elderly care services” for seniors fatigued by COVID-19 [Internet]. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2020. Jun. 8. [cited 2023 Oct 30]. https://www.korea.kr/news/policyNewsView.do?newsId=148873184.28. Thibaut F, van Wijngaarden-Cremers PJ. Women’s mental health in the time of Covid-19 pandemic. Front Glob Womens Health. 2020; 1:588372. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2020.588372.

Article29. McClelland H, Evans JJ, Nowland R, Ferguson E, O'Connor RC. Loneliness as a predictor of suicidal ideation and behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Affect Disord. 2020; 274:880–896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.004.

Article30. Ryu S, Nam HJ, Jhon M, Lee JY, Kim JM, Kim SW. Trends in suicide deaths before and after the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea. PLoS One. 2022; 17(9):e0273637. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273637.

Article31. Kwak SS. Depression among women in their 20s and 30s in the era of COVID-19 has increased significantly [Internet]. Seoul: Young Doctor;2021. Mar 10 [cited 2023 Oct 30]. Available from: https://www.docdocdoc.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=2008464.32. Leigh-Hunt N, Bagguley D, Bash K, Turner V, Turnbull S, Valtorta N, et al. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health. 2017; 152:157–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035.

Article33. Policy Briefing of Republic of Korea. Release of the 5th basic plan for suicide prevention [Internet]. Sejong: Ministry of Helath and Welfare;2023 Apr 14. [cited 2023 Nov 16]. Available from: https://www.korea.kr/briefing/policyBriefingView.do?newsId=156562783.34. Nordentoft M, Qin P, Helweg-Larsen K, Juel K. Restrictions in means for suicide: an effective tool in preventing suicide: the Danish experience. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007; 37(6):688–697. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2007.37.6.688.

Article35. Habenstein A, Steffen T, Bartsch C, Michaud K, Reisch T. Chances and limits of method restriction: a detailed analysis of suicide methods in Switzerland. Arch Suicide Res. 2013; 17(1):75–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2013.748418.

Article36. Denning DG, Conwell Y, King D, Cox C. Method choice, intent, and gender in completed suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2000; 30(3):282–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2000.tb00992.x.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Secular Trends of Suicide Mortality in Korea

- Suicide Related Indicators and Trends in Korea in 2021

- Trends and Risk Factors of the Epidemic of Charcoal Burning Suicide in a Recent Decade among Korean People

- Suicide Related Indicators and Trends in Korea in 2019

- Research trends in the Korean Journal of Women Health Nursing from 2011 to 2021: a quantitative content analysis