Korean J Phys Anthropol.

2014 Mar;27(1):11-28. 10.11637/kjpa.2014.27.1.11.

Maxillary Sinusitis from India: A Bio-cultural Approach

- Affiliations

-

- 1Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, India. vmushrif@gmail.com

- KMID: 1702841

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.11637/kjpa.2014.27.1.11

Abstract

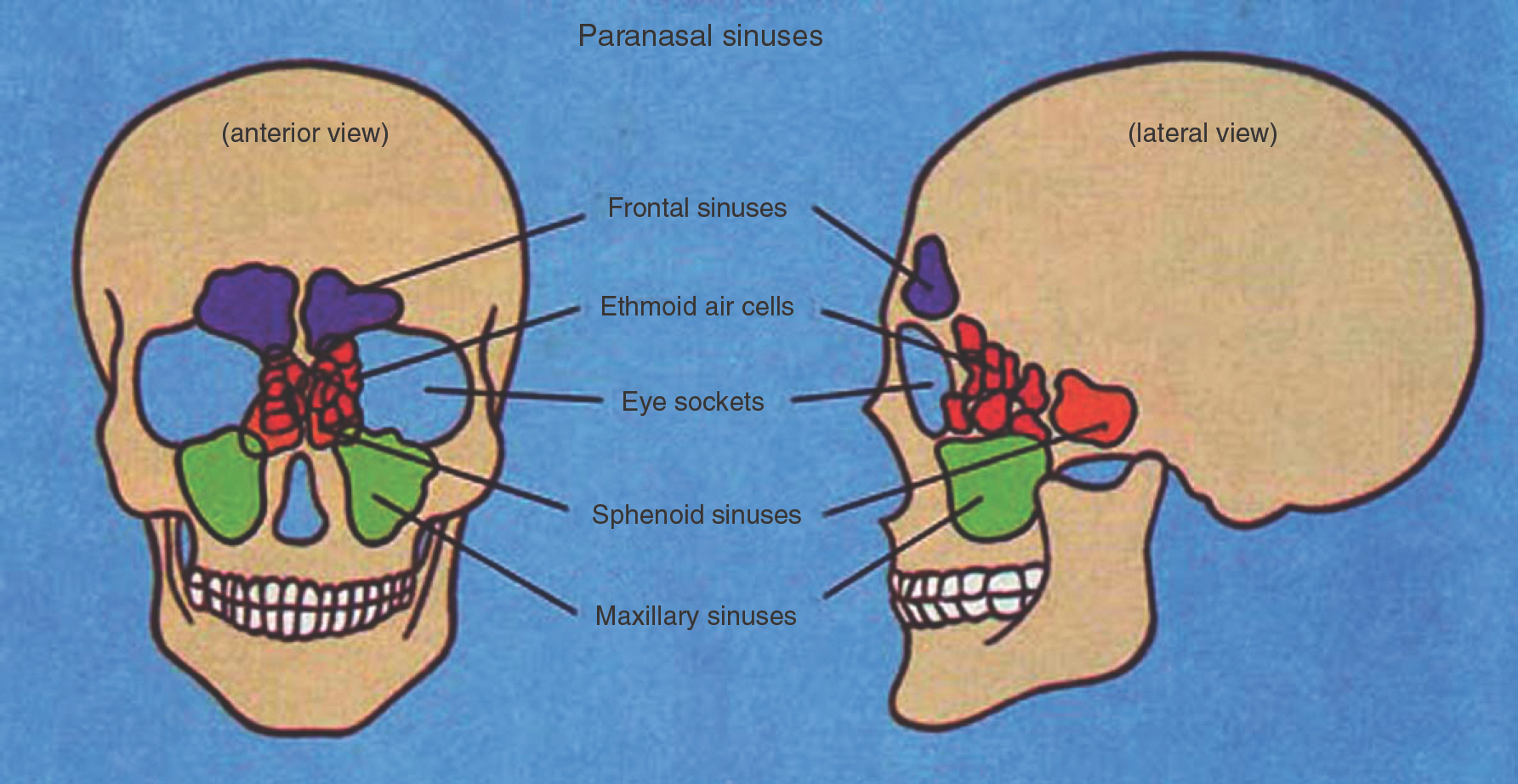

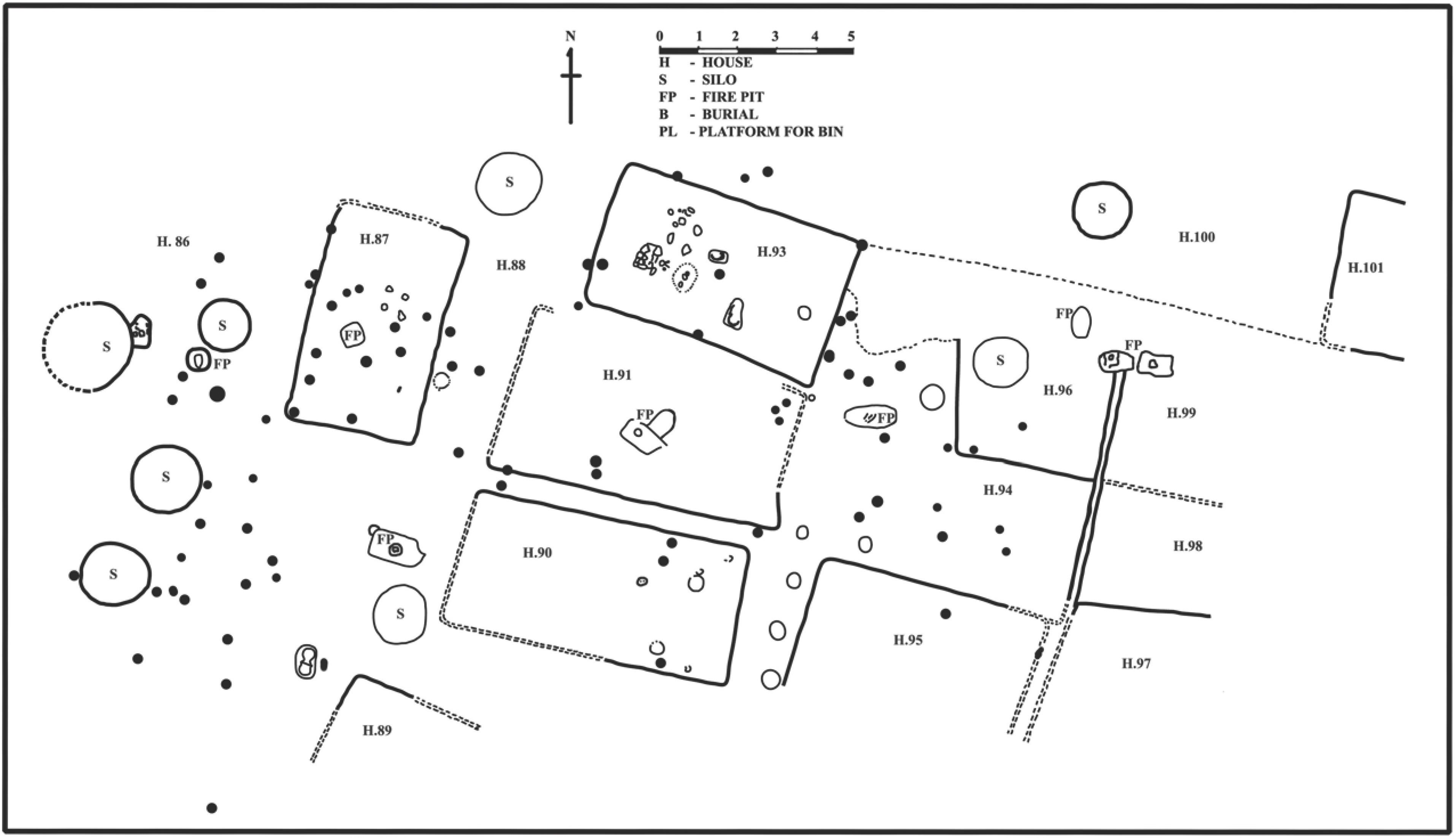

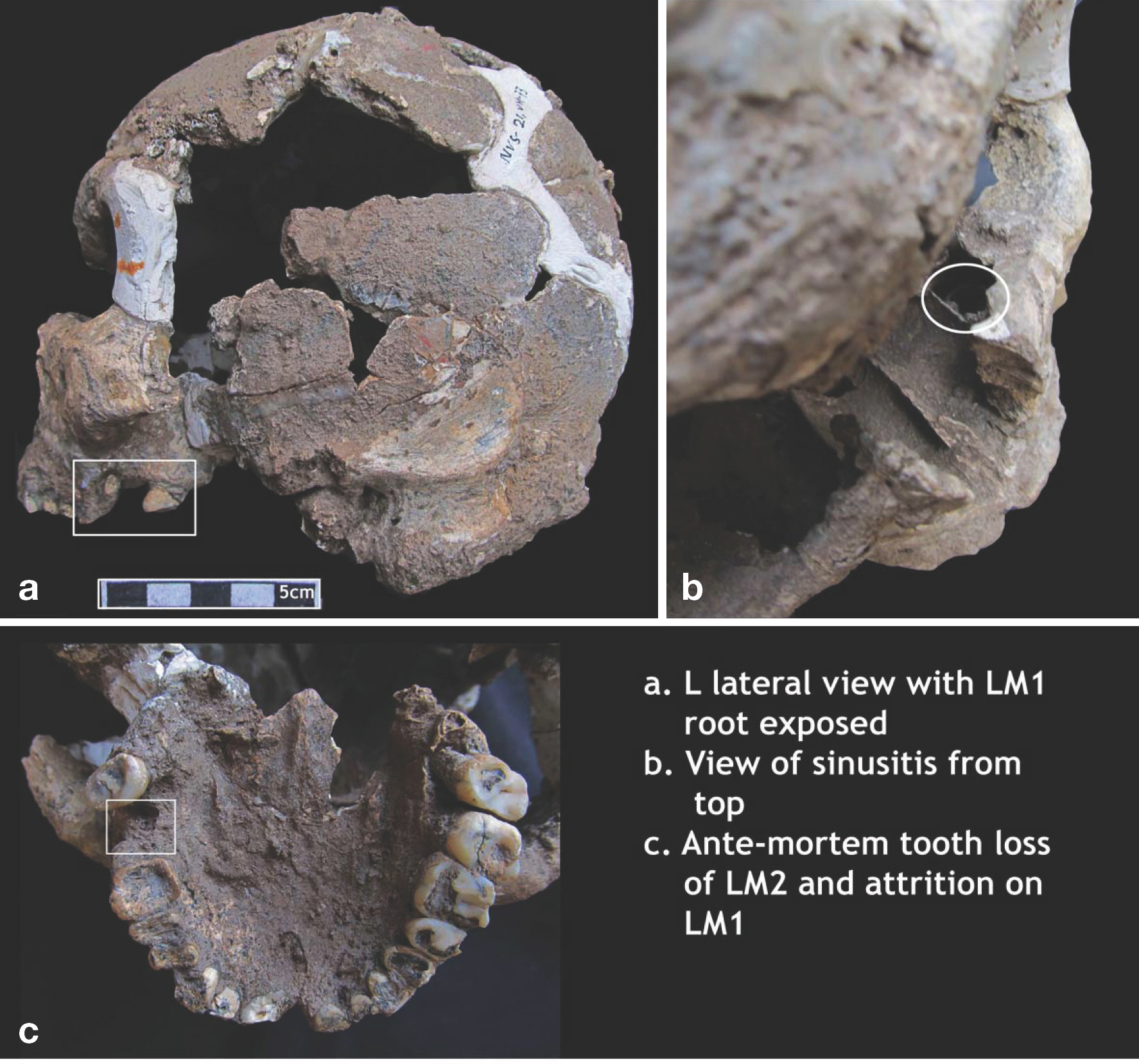

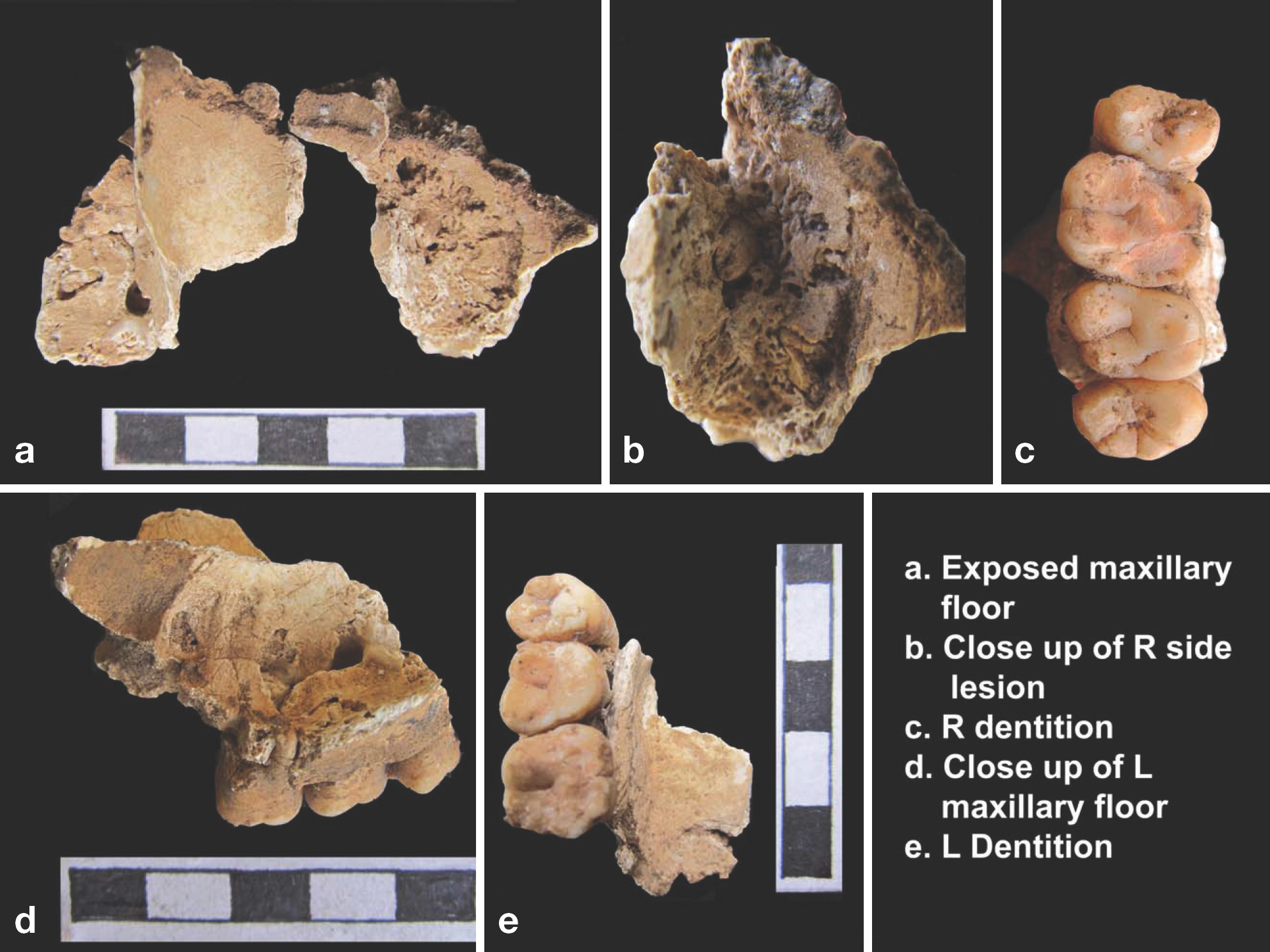

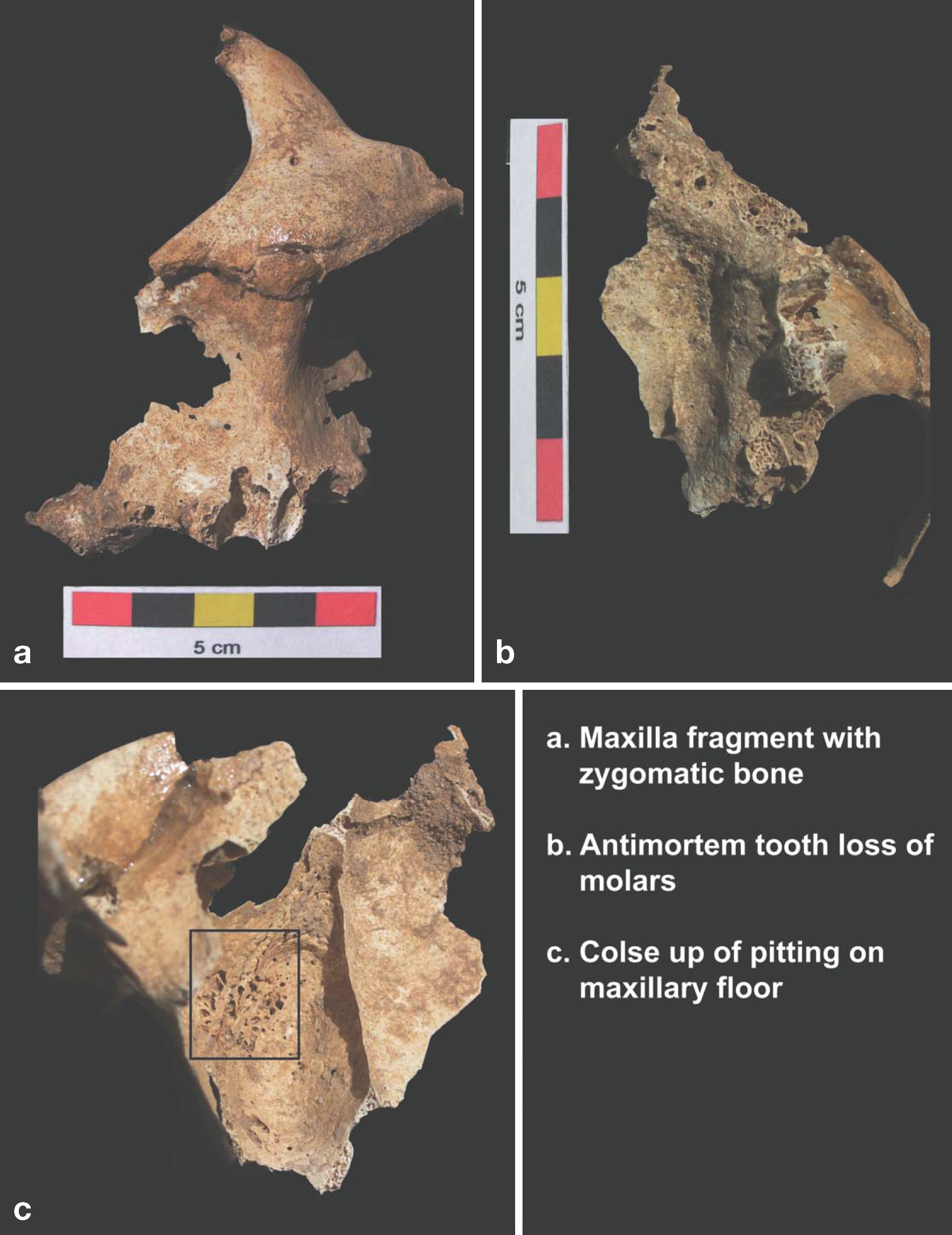

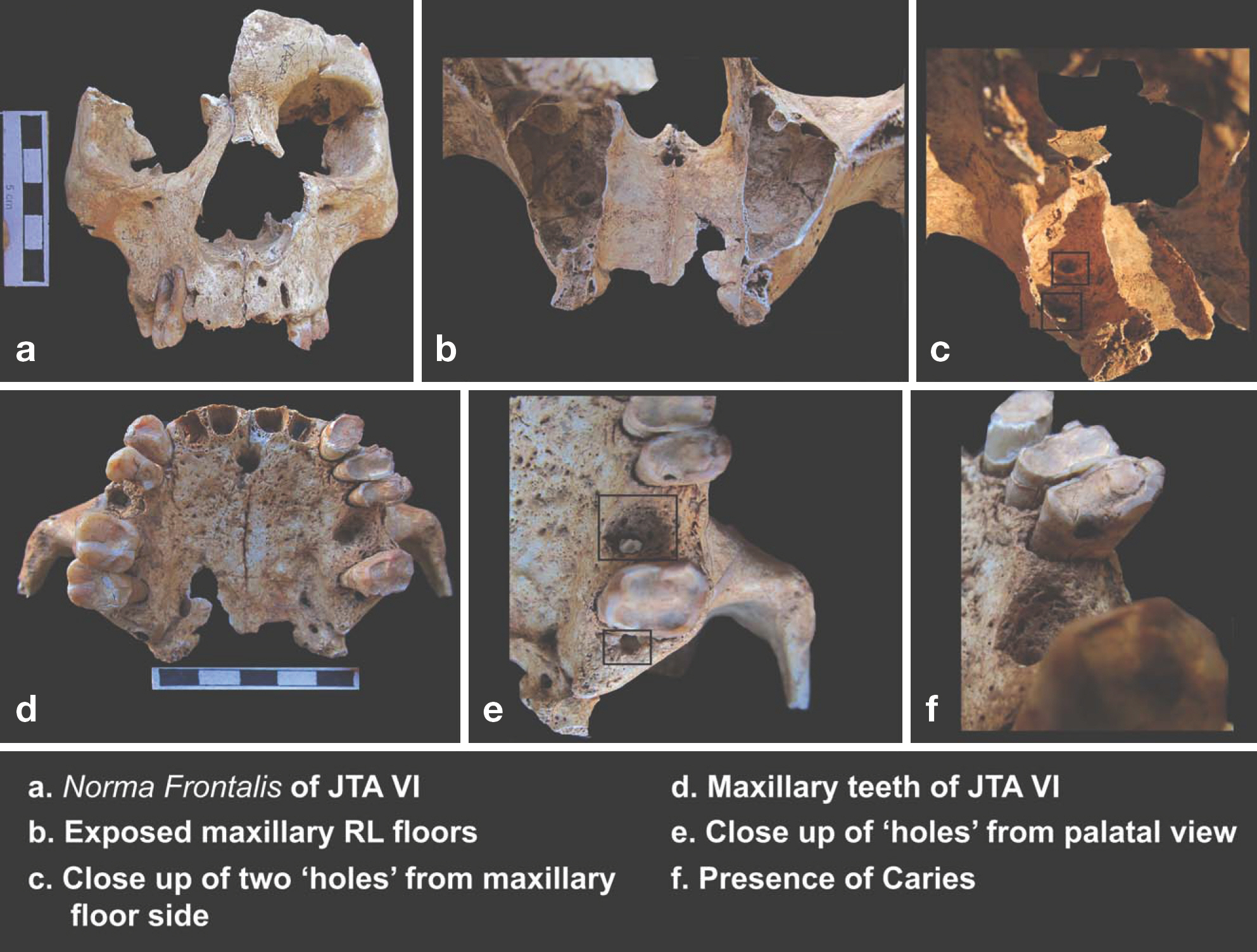

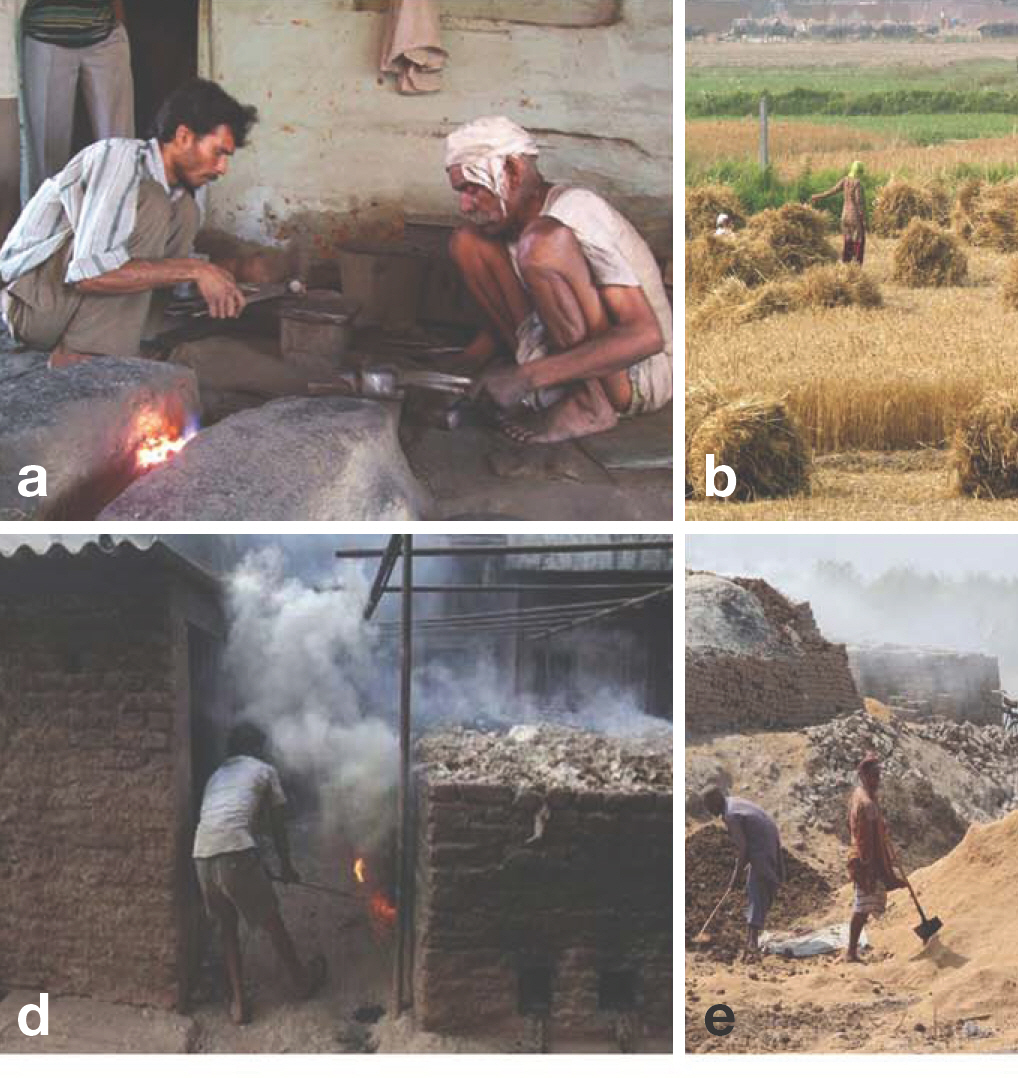

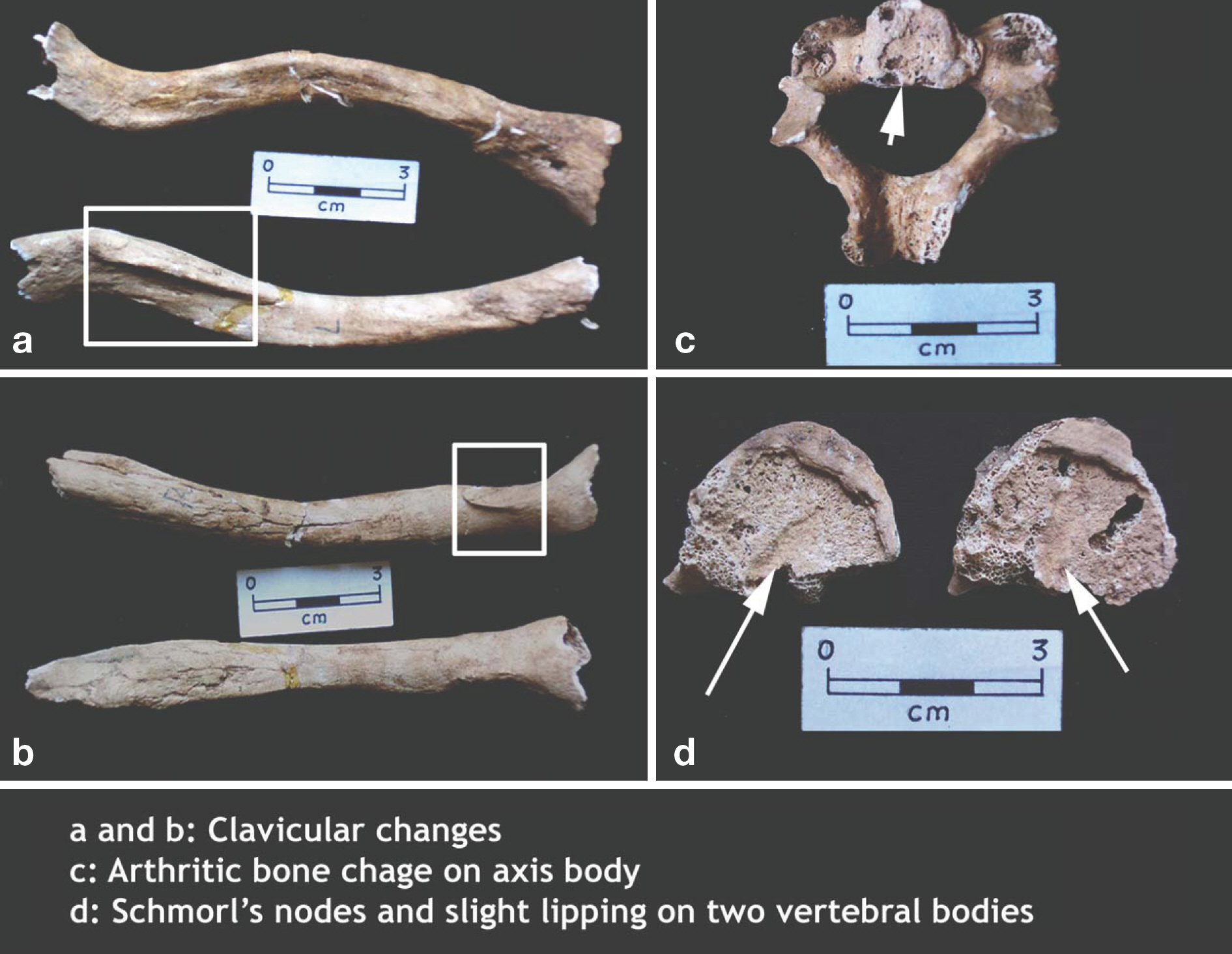

- This paper identifies the presence and etiology of maxillary sinusitis in archaeological populations from protohistoric (1500 B.C.) and medieval (around 17th century) India. 339 human skeleton remains found at the archaeological sites of Chalcolithic Nevasa (1500~600 B.C.), Inamgaon (1000~700 B.C.), Balathal (2000 B.C.), Megalithic Kodumanal (400 B.C.~100 A.D.), Early Historic Navdatoli (200 B.C.), Kodumanal (100~300 A.D.) and Jotsoma (17th c A.D.) were studied. Macroscopic physical examination revealed that 9 individuals out of 74 observable individuals (12.16%) suffered from inflammation. Of this, 6 were male while 3 were female. Considering the ethnographic aspects, the study reveals that inflammation possibly caused by inhaling polluted air for a long duration or because of dental disease. Also, apart from pollution in domestic zones, external pollution because of vocation is also discussed in this study using relevant ethnographic parallels.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Tales from Fragments: A Review of Indian Human Skeletal Studies

Veena Mushrif-Tripathy

Anat Biol Anthropol. 2019;32(2):43-52. doi: 10.11637/aba.2019.32.2.43.

Reference

-

References

1. Roberts CA. A bioarcheological study of maxillary sinusitis. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2007; 133:792–807.

Article2. Wells C. Chronic sinusitis with alveolar fistulae of mediaeval date. Journal of Laryngol Otol. 1964; 78:320–22.3. Merrett DC, Pfeiffer S. Maxillary sinusitis as in an indicator of respiratory health in past populations. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2000; 111:301–18.4. World Health Organization. Preventing disease through healthy environments. Geneva: World Health Organization;2006.5. Slavin RG, Sheldon L, Bernstein IL. The Diagnosis and management of Sinusitis: A Practise Parameter Update. Journal of Allergy ClinImmunol. 2005; 116:S13–S47.6. Chen BH, Hong CJ, Pandey MR. Indoor air pollution in developing countries. World Health Stat Q. 1990; 43:127–38.7. D'Souza RM. Housing and environmental factors and their effects on the health of children in the slums of Karachi, Pakistan. J Bio Soc Sci. 1997; 29:271–81.8. Wells C. Disease of maxillary sinus in antiquity. Medical and Biological Illustration. 1977; 27:173–8.9. Chen PCY. Longhouse dwelling, social contact and the prevalence of leprosy and tuberculosis among native tribes of Sarawak. Soc Sci Med. 1988; 26:1073–7.

Article10. Rajpandey M. Prevalence of chronic bronchitis in a rural community of the hill region of Nepal. Thorax. 1984; 39:331–9.11. Maestre-Ferrín L, Galán-Gil S, Carrillo-García C, Peñar-rocha-Diago M. Radiographic findings in the maxillary sinus: comparison of panoramic radiography with computed tomography. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2011; 26:341–6.12. Gregg JB, Gregg PS. Dry bones: Dakota territory reflected. An illustrative descriptive ananlysis of health and well being of previous people and culture as mirrored in their remains. Sioux Falls SD: Sioux Printing Press;1987.13. Boocock P, Roberts C, Manchester K. Maxillary sinusitis in Medieval Chichester, England. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1995; 98:483–95.

Article14. Panhuysen RGA, Coenen V, Bruintjes TD. Chronic maxil-lary sinusitis in medieval Maastrichi, The Netherlands. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 1997; 7:610–14.15. Lewis ME. Impact of industrialization: Comparative study of child health in four sites from medieval and post medieval England(A.D. 850–1859). Am J Phys Anthropol. 2002; 119:211–23.16. Buckley HR, Tayles N. Skeletal Pathology in a Prehistoric PacificIsland Sample: Issues in Lesion Recording, Quantification, and Interpretation. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2003; 122:303–24.17. Merrett D. Maxillary Sinusitis among the Moatfield people. In: Williamson RF, Pfeiffer S. editors. Bones of the ances-tors. The archaeology and osteobiography of the Moatfield Ossuary. Canada: Archaeological Survey of Canada (Mercury Series Archaeological Paper163). Canadian Museum of Civilization Gatineau, Quebec. 2003. ;p.241–61.18. Reddy NK. An ethnoarchaeological investigation into the maxillary sinusitis: Pathology of the Chalcolithic record. Unpublished M.A. Dissertation submitted to Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute. Pune;. 2002.19. Mushrif V, Walimbe SR. Human skeletal remains from Chalcolithic Nevasa: Osteobiographic analysis. London: British Archaeological Report, International Series;1476. p. 2006.20. Dhavalikar MK. The First Farmers of the Deccan. Pune: Ravish Publishers;1988. ;p.p. 13–4.21. Buikstra JE, Ubelaker DH. Standards for Data Collection from Human Skeletal Remains. Arkansas: Arkansas Archaeological Survey Research Series, No.44;1994.22. Lukacs JR, Walimbe SR. Excavations at Inamgaon, Volume II: The physical anthropology of human skeletal remains: Part i: An osteobiographic analysis. Pune: Deccan College Research Institute;1986.23. Mushrif-Tripathy V, Walimbe SR, Rajan K. Human skeletal remains from megalithic Kodumanal. Delhi: Aryan Books International;2011.24. Sankalia HD, Deo SB, Ansari ZD. Chalcolithic Navdatoli: The excavations at Navdatoli 1957–59. Poona-Baroda: Deccan College Research Institute and M.S. University Publi-cations;1971.25. Misra VN. Radiocarbon chronology of Balathal, district Udaipur, Rajasthan. Man and Environment. 2005; 30:54–60.26. Robbins G, Mushrif V, Misra VN, Mohanty RK, Shinde V. Biographies of the skeleton: Palaeopathological conditions at Balathal. Man and Environment. 2006; 31:50–65.27. Robbins G, Mushrif-Tripathy V, Misra VN, Mohanty RK, Shinde V, Gray KM, Schug MD. Ancient skeletal evidence for leprosy in India (2000 B.C.). PLoS ONE. 2009; 4(5):e5669. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0005669.

Article28. Reid TE, Shearer WT. Recurrent sinusitis and immunodeficiency. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 1994; 14:143–69.29. Hauhnar CZ, Kaur S, Sharma VK, Mann SBS. A clinical and radiological study of the maxillary antrum in lepromatous Leprosy. Indian Journal of Leprosy. 1992; 64:487–94.30. Mushrif-Tripahty V, Walimbe SR, Tosi J, Vasa D. 2009. Human skeletal remains from megalithic Jotsoma. Kolkata: Center for Archaeological Studies and Training, Eastern India;2009.31. Ortner DJ, Putschar WGJ. Identification of pathological conditions in human skeletal remains. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution;2003.32. Liebe-Harkort C. Cribra orbitalia, sinusitis and linear ena-mel hypoplasia in Swedish Roman iron age adults and sub-adults. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2010. [Epub].DOI: 10.1002/oa.1209.

Article33. Paju S, Bernstein JM, Haase EM, Scannapieco AF. Molecular analysis of bacterial flora associated with chronically inflamed maxillary sinuses. J Med Micro. 2003; 52:591–7.

Article34. Smith KR, Samet JM, Romieu I, Bruce N. Indoor air pollution in developing countries and acute lower respiratory infections in children. Thorax. 2000; 55:518–32.

Article35. Naeher LP, Leaderer BP, Smith KR. Particulate matter and carbon monoxide in highland Guatemala: Indoor and outdoor levels from traditional and improved wood stoves and gas stoves. Indoor Air. 2000a; 10:. 200–5.36. Saksena S, Singh PB, Prasad R, Prasad R, Malhotra P, Joshi V, et al. Exposure of infants to outdoor and indoor air pollution in low-income urban areas-A case study of Delhi. J Expos Analy and Environmental Epidemiology. 2003; 13:219–30.37. Fullerton DG, Semple S, Kalambo F, Suseno A, Malamba R, Henderson G, et al. Biomass fuel use and indoor air pollution in homes. Malawi Occup Environ Med. 2009; 66:777–83.38. Balakrishnan K, Ramaswamy P, Sambandam S, Thangavel G, Ghosh S, Johnson P, et al. Air pollution from household solid fuel combustion in India: an overview of exposure and health related information to inform health research priorities. Glob Health Action. 2011; 4:10. .3402/gha.v4i0.5638.

Article39. Naeher LP, Smith KR, Leaderer BP, Mage D, Grajeda R. Indoor and Outdoor PM2.5 and CO in high and low dentsity Guatemalan villages. J Exp Analy and Environmental Epidemiology. 2000b; 10:. 544–51.40. World Health Organization. Addressing the links between indoor air pollution, household energy and human health. Based on the WHO-USAID Consultation on the Health Impact of Household Energy in Developing Countries(Meeting report). Geneva, Additional information: ww.who.int/indoorair/publications/en/. 2002.41. Bruce N, Perez-Padilla R, Albalak R. Indoor air pollution in developing countries: a major environmental and public health challenge. Bull of the World Health Organization. 2000; 78:1078–92.42. Smith KR. Biofuels, Air Pollution, and Health: A Global Review. New York: Plenum;1987.43. Smith KR, Mehta S, Maeusezahl-Feuz M. Chapter 18: Indoor smoke from household use of solid fuels. Ezzati M, Rodgers A, Lopez AD, Hoorn SV, Murray CJL, editors. editors.Comparative quantification of health risks: The global burden of disease due to selected risk factors Vol 2. Geneva: World Health Organization;2004. ;p.p. 1435–93.44. Lewis ME, Roberts CA, Manchester K. Comparative study of the prevalence of maxillary sinusitis in later Medieval urban and rural populations in Northern England. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1995; 98:497–506.

Article45. Molleson T, Cox M. The Spital fields Project, Vol. 2: The anthropology. The middling sort(Council for British Archaeology Research Report 85). York: Council for British Archaeology;1993.46. McCurdy SA, Ferguson TJ, Goldsmith DF, Parker JE, Schenker MB. Respiratory health of Californian rice farmers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996; 153:1553–9.47. Mustajbegovic J, Zuskin E, Schachter EN, Kern J, Vrcic-Keglevic M, Heimer S, et al. Respiratory function in active firefighters. Am J Indus Med. 2001; 40:55–62.

Article48. Lukacs JR. Dental paleopathology: Methods for reconstructing dietary patterns. Iscan MY, Kennedy KAR, editors. editors.Reconstruction of life from skeleton. New York: Alan R. Liss;1989. p. 261–86.49. Cohen MN. Health and the rise of civilization. New York: Yale University Press;1989.50. Larsen CS. Bioarchaeology: Interpreting behaviour from the human skeleton. United Kingdom: Cambridge University press;1997.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A clinical study on maxillary sinusitis in children with respiratory allergic disease

- Modified Transseptal Approach: An Adjunct to Prelacrimal Recess Approach for Extensive Inverted Papilloma of Maxillary Sinus, How We Do It

- Treatment of dental implant-related maxillary sinusitis with functional endoscopic sinus surgery in combination with an intra-oral approach

- Delayed Occurrence of Maxillary Sinusitis after Simultaneous Maxillary Sinus Augmentation and Implant: A Case Report and Literature Review

- A clinical study on maxillary sinusitis in children with respiratory allergic disease