J Bacteriol Virol.

2013 Dec;43(4):270-278. 10.4167/jbv.2013.43.4.270.

Analysis of Oropharyngeal Microbiota between the Patients with Bronchial Asthma and the Non-Asthmatic Persons

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Microbiology, College of Medicine, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, Korea. kimwy@cau.ac.kr

- 2Division of Pulmonology and Allergology, Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Applied Statistics, Faculty of Business and Economics, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 1501995

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4167/jbv.2013.43.4.270

Abstract

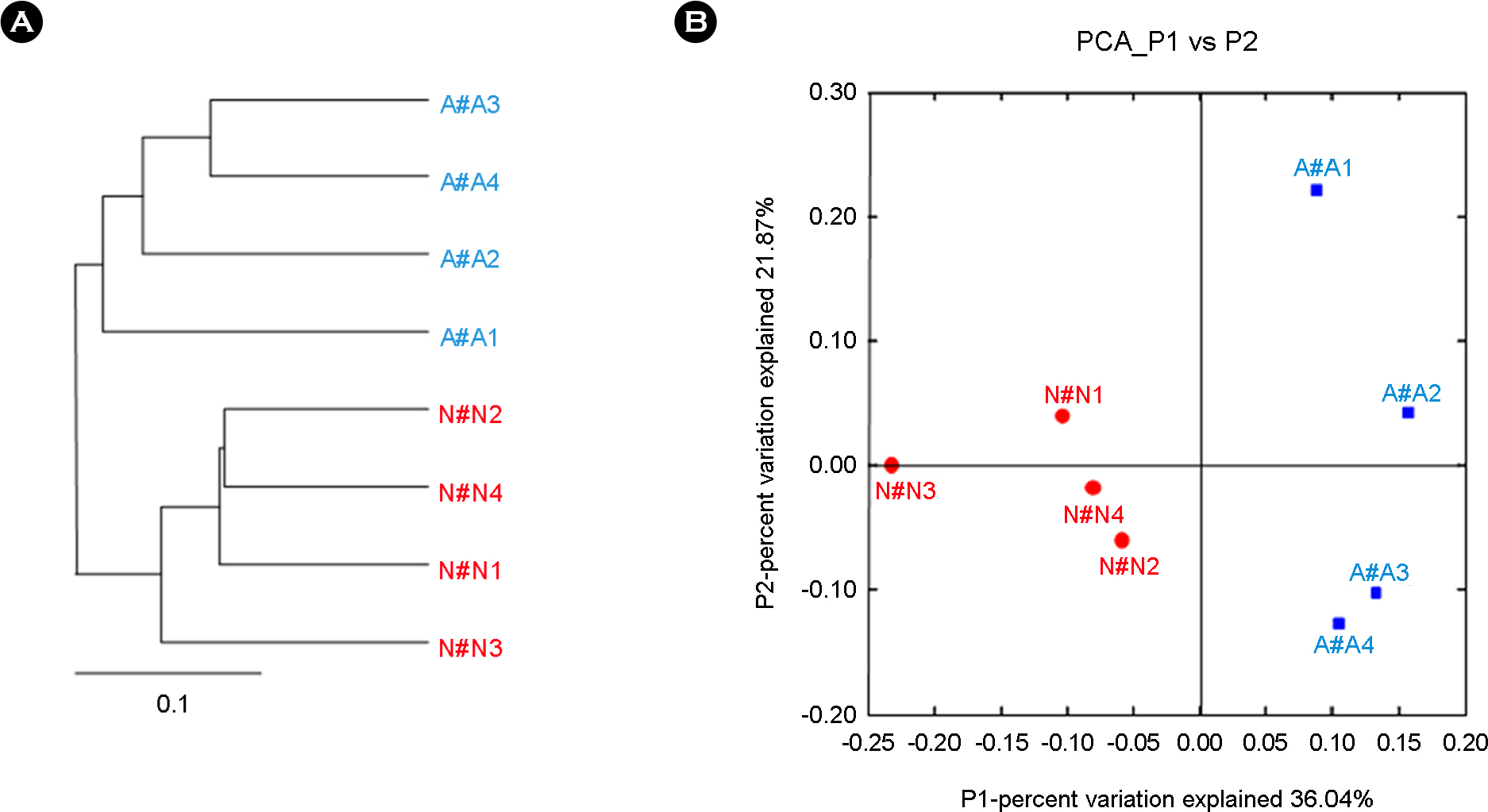

- Bronchial asthma can be triggered by microbial agents in the oropharynx. This study was designed to identify the differences in microbiota of oropharynx of bronchial asthmatic patients in contrast to normal controls. In order to resolve the qualitative and quantitative diversity of the 16S rRNA gene present in the oropharynx microbiota of 4 patients and 4 controls, we compared microbial communities using Sanger sequencing and 376 sequences of 16S rRNA gene were analyzed. Of the total microbial diversity detected in the oropharynx in asthmatic patients 45.6% comprised members of the Firmicutes. In contrast, Proteobacteria (44.0%) dominated the oropharyngeal microbiota in the normal control group. Members of the Bacteroidetes, Fusobacteria, Actinobacteria, TM7, Cyanobacteria and unclassified bacteria were present in both groups. In conclusion, the difference in the microbiota of the oropharynx between patients and normal individuals could trigger symptomatic attacks in bronchial asthma.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1). Ramsey CD, Gold DR, Litonjua AA, Sredl DL, Ryan L, Celedón JC. Respiratory illnesses in early life and asthma and atopy in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007; 119:150–6.

Article2). Fishman AJ, Weiss ST. Fishman's Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders. McGrawHill;2010.3). Johnston SL, Martin RJ. Chlamydophila pneumoniae and Mycoplasma pneumoniae: a role in asthma pathogenesis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005; 172:1078–89.4). Kraft M, Cassell GH, Pak J, Martin RJ. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae in asthma: effect of clarithromycin. Chest. 2002; 121:1782–8.5). Kraft M, Adler KB, Ingram JL, Crews AL, Atkinson TP, Cairns CB, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae induces airway epithelial cell expression of MUC5AC in asthma. Eur Respir J. 2008; 31:43–6.6). Kraft M, Cassell GH, Henson JE, Watson H, Williamson J, Marmion BP, et al. Detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the airways of adults with chronic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998; 158:998–1001.7). Dicksved J, Halfvarson J, Rosenquist M, Järnerot G, Tysk C, Apajalahti J, et al. Molecular analysis of the gut microbiota of identical twins with Crohn's disease. ISME J. 2008; 2:716–27.

Article8). Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006; 444:1022–3.9). Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Lozupone CA, Turnbaugh PJ, et al. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011; 108:4516–22.

Article10). Huffnagle GB. The microbiota and allergies/asthma. PLoS Pathog. 2010; 6:e1000549.

Article11). Noverr MC, Huffnagle GB. The ‘microflora hypothesis’ of allergic diseases. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005; 35:1511–20.

Article12). Parker JS, Monnet E, Powers BE, Twedt DC. Histologic examination of hepatic biopsy samples as a prognostic indicator in dogs undergoing surgical correction of congenital portosystemic shunts: 64 cases (1997–2005). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008; 232:1511–4.

Article13). Kim W. Application of metagenomic techniques: understanding the unrevealed human microbiota and explaining in the clinical infectious diseases. J Bacteriol Virol. 2012; 42:263–75.14). Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JGSK. Miniprep of bacterial genomic DNA. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York.:. 1993.15). Woese CR. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1987; 51:221–71.

Article16). Jonasson J, Olofsson M, Monstein HJ. Classification, identification and subtyping of bacteria based on pyrosequencing and signature matching of 16S rDNA fragments. APMIS. 2002; 110:263–72.

Article17). Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997; 25:4876–82.

Article18). Cole JR, Chai B, Farris RJ, Wang Q, Kulam-Syed-Mohideen AS, McGarrell DM, et al. The ribosomal database project (RDP-II): introducing myRDP space and quality controlled public data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007; 35:D169–72.

Article19). Lozupone C, Knight R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005; 71:8228–35.

Article20). Lozupone C, Hamady M, Knight R. UniFrac–an online tool for comparing microbial community diversity in a phylogenetic context. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006; 7:371.

Article21). Couzin-Frankel J. Bacteria and asthma: untangling the links. Science. 2010; 330:1168–9.

Article22). Blaser MJ. Who are we? Indigenous microbes and the ecology of human diseases. EMBO Rep. 2006; 7:956–60.23). Balkundi DR, Murray DL, Patterson MJ, Gera R, Scott-Emuakpor A, Kulkarni R. Penicillin-resistant Streptococcus mitis as a cause of septicemia with meningitis in febrile neutropenic children. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1997; 19:82–5.24). Cabellos C, Viladrich PF, Corredoira J, Verdaguer R, Ariza J, Gudiol F. Streptococcal meningitis in adult patients: current epidemiology and clinical spectrum. Clin Infect Dis. 1999; 28:1104–8.

Article25). Lu HZ, Weng XH, Zhu B, Li H, Yin YK, Zhang YX, et al. Major outbreak of toxic shock-like syndrome caused by Streptococcus mitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2003; 41:3051–5.26). Lyytikäinen O, Rautio M, Carlson P, Anttila VJ, Vuento R, Sarkkinen H, et al. Nosocomial bloodstream infections due to viridans streptococci in haematological and non-haematological patients: species distribution and antimicrobial resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004; 53:631–4.27). Koren O, Spor A, Felin J, Fåk F, Stombaugh J, Tremaroli V, et al. Human oral, gut, and plaque microbiota in patients with atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011; 108:4592–8.

Article28). Chalmers NI, Palmer RJ Jr, Cisar JO, Kolenbrander PE. Characterization of a Streptococcus sp.-Veillonella sp. community micromanipulated from dental plaque. J Bacteriol. 2008; 190:8145–54.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Late asthmatic responses and consequences on nonspecific bronchial reactivity after exercise and allergen challanges in the children with bronchial asthma

- Relationship Between Atopy and Bronchial Hyperresponsiveness

- The Allergen Shin Test and the Effect of Specific Desensitization in Bronchial Asthma

- Newly sensitization to house dust mite in an isocyanate-induced asthmatic patient

- Effects of Stellate Ganglion block for the Treatment of Bronchial Asthmatic Patients: 3 cases report