Korean J Clin Microbiol.

2010 Sep;13(3):103-108. 10.5145/KJCM.2010.13.3.103.

Outbreak of Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1); Experience of a Regional Center in Seoul during a Month, August-September 2009

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Laboratory Medicine, Sanggye Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. bmshin@unitel.co.kr

- 2Department of Infection Control Office, Sanggye Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Urology, Sanggye Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Department of Internal Medicine, Sanggye Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 5Department of Pediatrics, Sanggye Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 6Department of Family Medicine, Sanggye Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 7Department of Emergency Medicine, Sanggye Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 1461617

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5145/KJCM.2010.13.3.103

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

The aim of this study is to clarify the epidemiology of swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus 2009 (S-OIV) during the first month of outbreak at one of influenza clinic in Seoul, Korea.

METHODS

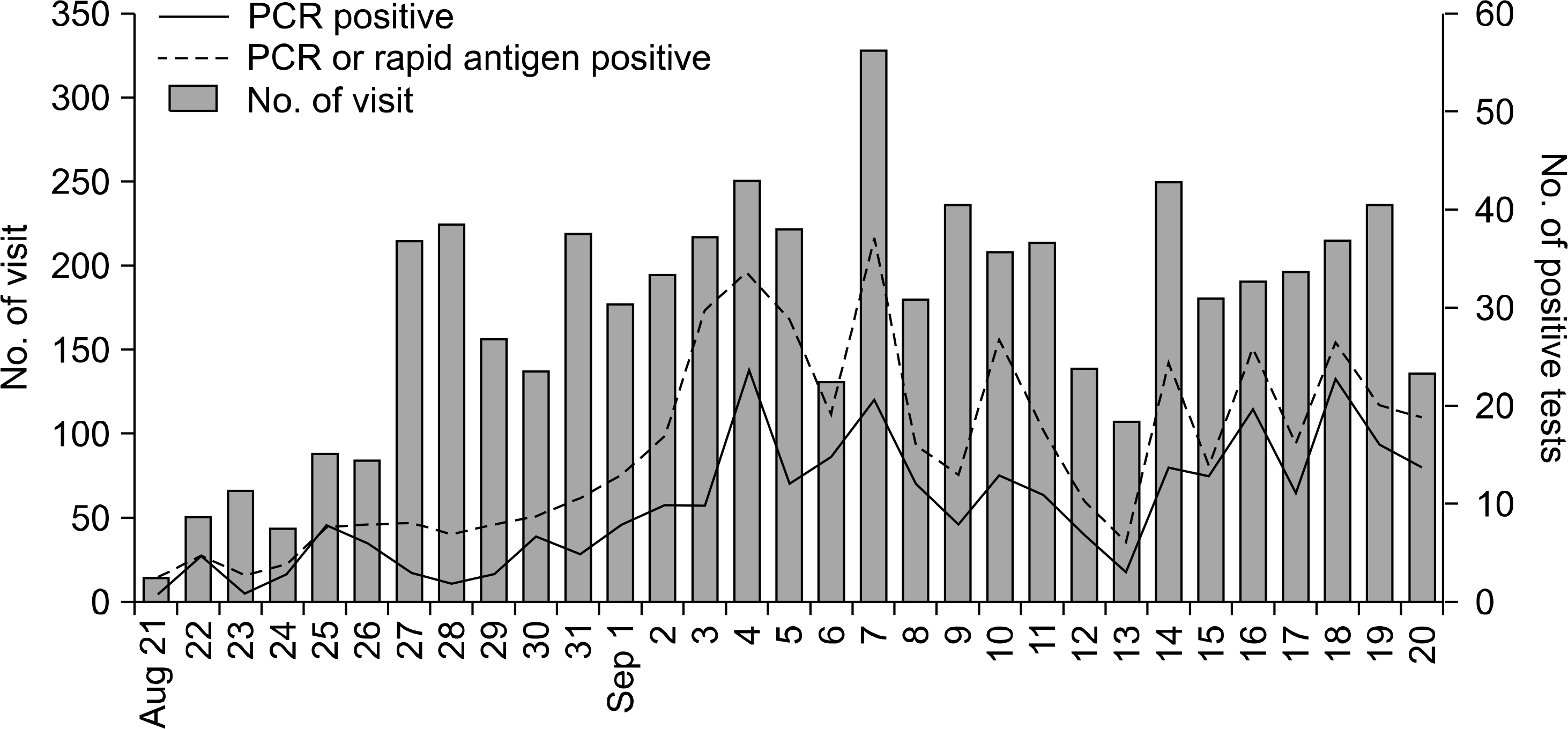

We documented the epidemiologic and clinical features of S-OIV-confirmed cases who visited a university hospital in Northeastern Seoul between August 21 and September 20, 2009. Nasopharyngeal swab of patients with acute febrile respiratory illnesses were evaluated with rapid influenza antigen tests and multiplex RT-PCR for S-OIV and seasonal influenza A.

RESULTS

A total of 5,322 patients with acute febrile respiratory illnesses were identified at our influenza clinic for the study period. S-OIV was confirmed in 309 patients by RT-PCR. The patients ranged from 2 months to 61 years of age and 189 patients (61.2%) were teenagers. Eighty-one patients had known contact with S-OIV-confirmed patients in schools (N=61), households (N=15), and healthcare facilities (N=3). Frequent symptoms were fever (94.5%), cough (73.1%), sore throat (52.1%), and rhinorrhea (50.5%). Gastrointestinal symptoms were also present in 10 patients (4.9%). Ten patients (4.9%) required hospitalizations. Seventy patients (22.7%) could not take oseltamivir at the first visits, however, all of them recovered without complication. Rapid antigen tests showed the sensitivity of 44.4% (130/294). Patients with positive antigen tests, compared with negative antigen tests, showed higher frequencies of rhinorrhea (60.8% vs 43.3%, P=0.004) and stuffy nose (33.8% vs 20.1%, P=0.012).

CONCLUSION

S-OIV infections spread predominately in school-aged children during the early accelerating phase of the outbreak. Rapid influenza antigen tests were correlated with nasal discharge and obstruction.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Investigation Team. Dawood FS, Jain S, Finelli L, Shaw MW, Lindstrom S, Garten RJ, et al. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:2605–15.

Article2. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnostic criteria of swein A (H1N1) infection. http://flu.cdc.go.kr. [online] (last visited on 10 May 2009).3. Chun JY, Kim KJ, Hwang IT, Kim YJ, Lee DH, Lee IK, et al. Dual priming oligonucleotide system for the multiplex detection of respiratory viruses and SNP genotyping of CYP2C19 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007; 35:e40.

Article4. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza sentinel surveillance report. http://flu.cdc.go.kr. [online] (last visited on 10 May 2009).5. Kim BN, Kwak YG, Moon CS, Kim YS, Kim ES, Bae IG, et al. Trend in age distribution of visitors to flu-clinics during the pandemic influenza (H1N1 2009). Infect Chemother. 2010; 42:90–4.

Article6. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National level response to Pandemic A(H1N1) 2009. Public Health Weekly Report. 2010; 3:241–6.7. Health Protection Agency; Health Protection Scotland; National Public Health Service for Wales; HPA Northern Ireland Swine influenza investigation teams. Epidemiology of new influenza A (H1N1) virus infection, United Kingdom, April-June 2009. Euro Surveill. 2009; 14:pii: 19232.8. Noh JY, Yim SY, Heo JY, Choi WS, Song JY, Cheong HJ, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of pandemic influenza (H1N1 2009). Infect Chemother. 2010; 42:69–75.

Article9. Vasoo S, Stevens J, Singh K. Rapid antigen tests for diagnosis of pandemic (Swine) influenza A/H1N1. Clin Infect Dis. 2009; 49:1090–3.

Article10. Chan KH, Lai ST, Poon LL, Guan Y, Yuen KY, Peiris JS. Analytical sensitivity of rapid influenza antigen detection tests for swine-origin influenza virus (H1N1). J Clin Virol. 2009; 45:205–7.

Article11. Faix DJ, Sherman SS, Waterman SH. Rapid-test sensitivity for novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:728–9.

Article12. Uyeki TM, Prasad R, Vukotich C, Stebbins S, Rinaldo CR, Ferng YH, et al. Low sensitivity of rapid diagnostic test for influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 2009; 48:e89–92.

Article13. Hwang Y, Kim K, Lee M. Evaluation of the efficacies of rapid antigen test, multiplex PCR, and realtime PCR for the detection of a novel influenza A (H1N1) virus. Korean J Lab Med. 2010; 30:147–52.

Article14. Rouleau I, Charest H, Douville-Fradet M, Skowronski DM, De Serres G. Field performance of a rapid diagnostic test for influenza in an ambulatory setting. J Clin Microbiol. 2009; 47:2699–703.

Article15. Bellei N, Benfica D, Perosa AH, Carlucci R, Barros M, Granato C. Evaluation of a rapid test (QuickVue) compared with the shell vial assay for detection of influenza virus clearance after antiviral treatment. J Virol Methods. 2003; 109:85–8.

Article16. Kim YK, Kim HY, Uh Y, Chun JK. Detection rate of rapid antigen test for pandemic influenza A (H1N1 2009). Infect Chemother. 2010; 42:95–8.

Article17. Heo JY, Noh JY, Jo YM, Choi WS, Song JY, Jim WJ, et al. Clincal usefulness of a rapid antigen test for novel influenza A (H1N1) virus. Infect Chemother. 2009; 41(Suppl 2):S198.18. Moscona A. Medical management of influenza infection. Annu Rev Med. 2008; 59:397–413.

Article19. Moscona A. Global transmission of oseltamivir-resistant influenza. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:953–6.

Article20. Bright RA, Medina MJ, Xu X, Perez-Oronoz G, Wallis TR, Davis XM, et al. Incidence of adamantane resistance among influenza A (H3N2) viruses isolated worldwide from 1994 to 2005: a cause for concern. Lancet. 2005; 366:1175–81.

Article21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Oseltamivir-resistant novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in two immunosuppressed patients - Seattle, Washington, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009; 58:893–6.22. Hong HL, Kim JH, Yi HJ, Kwon HH. A case of oseltamivir-resistant pandemic influenza (H1N1 2009). Infect Chemother. 2010; 42:103–6.

Article23. Sheu TG, Deyde VM, Okomo-Adhiambo M, Garten RJ, Xu X, Bright RA, et al. Surveillance for neuraminidase inhibitor resistance among human influenza A and B viruses circulating worldwide from 2004 to 2008. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008; 52:3284–92.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Novel swine-origin H1N1 influenza

- Experience for S-OIV of Admission Pediatric Patient with S-OIV at YUMC, 2009

- Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and management of pandemic novel Influenza A (H1N1)

- Constrictive Pericarditis Accompanied by Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Infection

- Influenza Associated Pneumonia