Korean Circ J.

2010 Sep;40(9):434-441. 10.4070/kcj.2010.40.9.434.

Subclinical Coronary Artery Disease as Detected by Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography in an Asymptomatic Population

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. ohbhmed@snu.ac.kr

- 2Division of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Center Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea.

- 3Division of Radiology, Cardiovascular Center Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea.

- KMID: 1456135

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2010.40.9.434

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

Primary prevention of coronary artery disease (CAD) has become a public health issue, according to increasing awareness of the substantial risks posed by asymptomatic atherosclerosis. The aims of this study were to determine the prevalence and characteristics of subclinical CAD using coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA), and to evaluate the role of this advanced technology in identifying subclinical CAD in asymptomatic Korean individuals, compared with conventional risk stratification.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

We enrolled 4,320 consecutive asymptomatic individuals (61% males, aged 50+/-9 years), who underwent 64-slice CCTA during a routine health check.

RESULTS

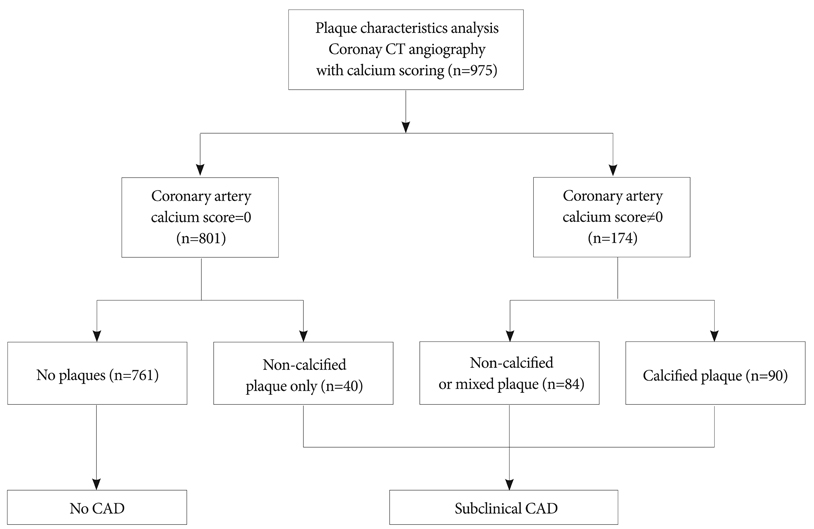

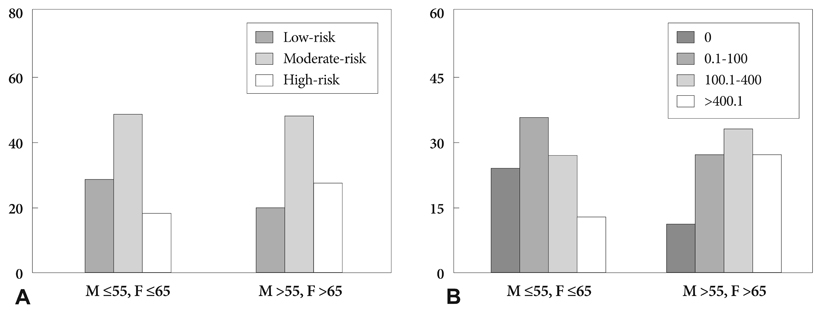

Coronary artery plaques were present in 1,053 (24%) individuals. Significant stenosis (diameter stenosis > or =50%) was identified in 139 (3%) subjects, and most of the significant lesions (87%) were located in the left anterior descending artery. CCTA revealed noncalcified plaques in 5% of subjects with a coronary calcium score of zero (n=801). Although 25% (n=10) of those with noncalcified plaque had significant stenosis, most of them (90%) were classified into low- or moderate-risk groups according to National Cholesterol Education Program risk stratification guidelines. In a young population (age < or =55 years for males, < or =65 years for females), 30% of subjects with significant stenosis were classified into a low-risk group and 60% had low (0 to 100) calcium scores.

CONCLUSION

Subclinical CAD in asymptomatic individuals cannot be ignored for its considerable prevalence, CCTA may be helpful in identifying at-risk subclinical CAD in a noninvasive manner, especially in the young and traditionally low-risk population.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Comparison of Coronary Plaque and Stenosis Between Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography and Virtual Histology-Intravascular Ultrasound in Asymptomatic Patients with Risk Factors for Coronary Artery Disease

Young Joon Hong, Myung Ho Jeong, Yun Ha Choi, Soo Young Park, Hyun Ju Seon, Hyun Sung Lee, Yun Hyun Kim, Sang Cheol Cho, Jae Young Cho, Hae Chang Jeong, Soo Young Jang, Jong Hyun Yoo, Ji Eun Song, Ki Hong Lee, Keun Ho Park, Doo Sun Sim, Nam Sik Yoon, Hyun Ju Yoon, Kye Hun Kim, Hyung Wook Park, Ju Han Kim, Youngkeun Ahn, Jeong Gwan Cho, Jong Chun Park, Jung Chaee Kang

J Lipid Atheroscler. 2014;3(2):79-87. doi: 10.12997/jla.2014.3.2.79.

Reference

-

1. Compressed mortality file: underlying cause of death, 1979 to 2005. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed May 29, 2008. Atlanta, Ga: centers for disease control and prevention;Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/mortSQL.html.2. Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009. 119:e21–e181.3. Boland LL, Folsom AR, Sorlie PD, et al. Occurrence of unrecognized myocardial infarction in subjects aged 45 to 65 years (the ARIC Study). Am J Cardiol. 2002. 90:927–931.4. Zelinger A, Wayhs R, Graboys TB, Tavel ME. Asymptomatic coronary artery disease: choices in evaluation. Chest. 2002. 121:1684–1687.5. Cho Y, Yoon Y, Kim J, et al. Comparison of primary prevention strategies for coronary heart disease in asymptomatic individuals: the National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III guideline versus the screening for heart attack prevention and education guideline. Korean Circ J. 2008. 38:483–490.6. Akosah KO, Schaper A, Cogbill C, Schoenfeld P. Preventing myocardial infarction in the young adult in the first place: how do the National Cholesterol Education Panel III guidelines perform? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003. 41:1475–1479.7. Froelicher VF, Thompson AJ, Longo MR Jr, Triebwasser JH, Lancaster MC. Value of exercise testing for screening asymptomatic men for latent coronary artery disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1976. 18:265–276.8. Pilote L, Pashkow F, Thomas JD, et al. Clinical yield and cost of exercise treadmill testing to screen for coronary artery disease in asymptomatic adults. Am J Cardiol. 1998. 81:219–224.9. Thaulow E, Erikssen J, Sandvik L, Erikssen G, Jorgensen L, Cohn PF. Initial clinical presentation of cardiac disease in asymptomatic men with silent myocardial ischemia and angiographically documented coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1993. 72:629–633.10. Rumberger JA, Simons DB, Fitzpatrick LA, Sheedy PF, Schwartz RS. Coronary artery calcium area by electron-beam computed tomography and coronary atherosclerotic plaque area: a histopathologic correlative study. Circulation. 1995. 92:2157–2162.11. Arad Y, Spadaro LA, Goodman K, Newstein D, Guerci AD. Prediction of coronary events with electron beam computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000. 36:1253–1260.12. Rumberger JA, Brundage BH, Rader DJ, Kondos G. Electron beam computed tomographic coronary calcium scanning: a review and guidelines for use in asymptomatic persons. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999. 74:243–252.13. Budoff MJ, Shaw LJ, Liu ST, et al. Long-term prognosis associated with coronary calcification: observations from a register of 25,253 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007. 49:1860–1870.14. Naghavi M, Falk E, Hecht HS, et al. From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient: part III. executive summary of the screening for Heart Attack Prevention and Education (SHAPE) Task Force report. Am J Cardiol. 2006. 98:2H–15H.15. Kim KS. Imaging markers of subclinical atherosclerosis. Korean Circ J. 2007. 37:1–8.16. Achenbach S. Computed tomography coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006. 48:1919–1928.17. Choi YS, Youn HJ, Jung SE, et al. The association between coronary artery calcification on MDCT and angiographic coronary artery stenosis. Korean Circ J. 2007. 37:167–172.18. Choi EK, Choi SI, Rivera JJ, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography as a screening tool for the detection of occult coronary artery disease in asymptomatic individuals. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008. 52:357–365.19. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002. 106:3143–3421.20. Min JK, Shaw LJ, Devereux RB, et al. Prognostic value of multidetector coronary computed tomographic angiography for prediction of all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007. 50:1161–1170.21. Watkins SP, Andrews TC. Guidelines for interpretation of electron beam computed tomography calcium scores from the Dallas Heart Disease Prevention Project. Am J Cardiol. 2001. 87:1387–1388.22. O'Rourke RA, Brundage BH, Froelicher VF, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Expert Consensus document on electron-beam computed tomography for the diagnosis and prognosis of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2000. 102:126–140.23. Rubinshtein R, Gaspar T, Halon DA, Goldstein J, Peled N, Lewis BS. Prevalence and extent of obstructive coronary artery disease in patients with zero or low calcium score undergoing 64-slice cardiac multi-detector computed tomography for evaluation of a chest pain syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2007. 99:472–475.24. Cheng VY, Lepor NE, Madyoon H, Eshaghian S, Naraghi AL, Shah PK. Presence and severity of non-calcified coronary plaque on 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography in patients with zero and low coronary artery calcium. Am J Cardiol. 2007. 99:1183–1186.25. Ehara M, Surmely JF, Kawai M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 64-slice computed tomography for detecting angiographically significant coronary artery stenosis in an unselected consecutive patient population: comparison with conventional invasive angiography. Circ J. 2006. 70:564–571.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Unusual Coronary Artery Fistula: Left Anterior Descending Coronary Artery - Left Ventricular Fistula Diagnosed by ECG-Gated Multi-Detector Row Coronary CT Angiography

- Significance of Microalbuminuria in Relation to Subclinical Coronary Atherosclerosis in Asymptomatic Nonhypertensive, Nondiabetic Subjects

- Detection of a Left Main Coronary Aneurysm with a Thrombus Presenting as an Acute Myocardial Infarction by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography

- A Single Coronary Artery: Right Coronary Artery Originating From the Distal Left Circumflex Artery

- Diabetes and Subclinical Coronary Atherosclerosis