Yonsei Med J.

2012 Mar;53(2):450-453. 10.3349/ymj.2012.53.2.450.

Identification of Vulnerable Plaque in a Stented Coronary Segment 17 Years after Implantation Using Optical Coherence Tomography

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Medicine, Cardiac and Vascular Center, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. youngbin.song@gmail.com

- KMID: 1120218

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2012.53.2.450

Abstract

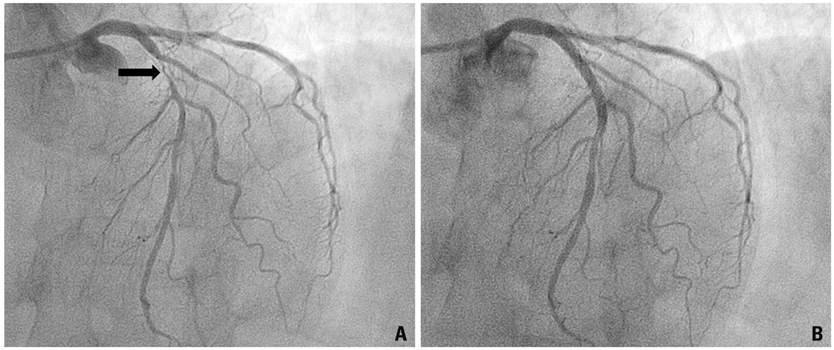

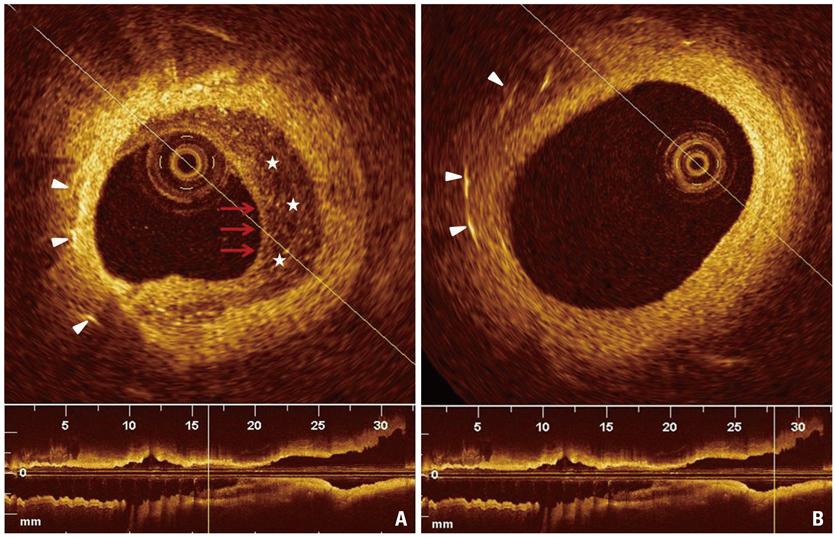

- A patient presented with exertional chest pain two months prior to admission. Coronary angiography revealed a subocclusive stenosis within the boundaries of the stent. Optical coherence tomography showed remarkable intimal growth inside the stent, which demonstrated a heterogeneous appearance including low-intensity areas. These findings were congruent with the morphology of fibroatheroma in the native coronary artery and suggested that new atherosclerotic progression of the intima within the stent had occurred over 17 years following bare metal stent implantation. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the most delayed instances of a bare metal stent restenosis described in the medical literature.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Yutani C, Imakita M, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Tsukamoto Y, Nishida N, Ikeda Y. Coronary atherosclerosis and interventions: pathological sequences and restenosis. Pathol Int. 1999. 49:273–290.

Article2. Yokoyama S, Takano M, Yamamoto M, Inami S, Sakai S, Okamatsu K, et al. Extended follow-up by serial angioscopic observation for bare-metal stents in native coronary arteries: from healing response to atherosclerotic transformation of neointima. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009. 2:205–212.

Article3. Habara M, Terashima M, Suzuki T. Detection of atherosclerotic progression with rupture of degenerated in-stent intima five years after bare-metal stent implantation using optical coherence tomography. J Invasive Cardiol. 2009. 21:552–553.4. Kimura T, Abe K, Shizuta S, Odashiro K, Yoshida Y, Sakai K, et al. Long-term clinical and angiographic follow-up after coronary stent placement in native coronary arteries. Circulation. 2002. 105:2986–2991.

Article5. Hasegawa K, Tamai H, Kyo E, Kosuga K, Ikeguchi S, Hata T, et al. Histopathological findings of new in-stent lesions developed beyond five years. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006. 68:554–558.

Article6. Gonzalo N, Serruys PW, Okamura T, van Beusekom HM, Garcia-Garcia HM, van Soest G, et al. Optical coherence tomography patterns of stent restenosis. Am Heart J. 2009. 158:284–293.

Article7. Inoue K, Abe K, Ando K, Shirai S, Nishiyama K, Nakanishi M, et al. Pathological analyses of long-term intracoronary Palmaz-Schatz stenting; is its efficacy permanent? Cardiovasc Pathol. 2004. 13:109–115.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Acute coronary syndrome and vulnerable plaque

- Successful Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention without Stenting: Insight from Optimal Coherence Tomography

- Stent Evaluation with Optical Coherence Tomography

- A Newly Formed and Ruptured Atheromatous Plaque within Neointima after Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation: 2-Year Follow-Up Intravascular Ultrasound and Optical Coherence Tomography Studies

- Optimization of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Using Optical Coherence Tomography